Zsolt Gyenge

zsgyenge@mome.hu

This is Not Magritte

Corneliu Porumboiu’s Theory of Representation[1] (downloan pdf)

“Porumboiu is a filmmaker obsessed with definitions and signs.”

Alice Bardan

Abstract: Maria Ioniță in her paper on Corneliu Porumboiu compares the director’s work to Magritte, arguing that both reflect on a “fundamental incompatibility of the visual and the linguistic”. The paper will thoroughly analyze the theoretical implications of the director’s “visual philosophy”, and will interpret Porumboiu’s cinematic quest from this point of view. The starting point of the paper is that his films can be interpreted as “direct theory” – a term introduced by Edward S. Small to describe the way in which experimental films and video works are directly creating a certain type of theory, without being confined to linguistic expression.

The questions related to the possibilities and boundaries of representation raised by Porumboiu’s films will be grouped in five thematic chapters, where the theoretical discussions will be accompanied by the close analysis of several scenes. First the relationship of the verbal and the visual will be analyzed based on Foucault’s view on Magritte; then Barthes’ and Gadamer’s theories on the differences between signs, symbols and images will be compared; afterwards I will assess the role of mediality following Mitchell’s analysis; I will also focus on the perception and expression of experience from a phenomenological point of view, and finally I will take a look on representation and definition understood as a practice of power, where the power over the system of signification affects the medium’s capacity of representation.

An important goal of the paper is to leave behind the usual discourse on realism, neorealism and a non-defined though often mentioned minimalism that has almost completely dominated the critical and scholarly reception of the new Romanian cinema. Instead I will try to prove that a focus on the mediality of perception, communication and representation can provide a more sophisticated interpretation of Porumboiu’s cinema.

Keywords: Corneliu Porumboiu; representation theory; Romanian New Wave; semiotics; phenomenology

Minimalism, realism, neo-realism – these are the terms most often used to describe the Romanian New Wave in the critical and scholarly discourse. As Maria Ioniță writes, since 2001 Romanian cinema “has been increasingly associated with a distinctive brand of realism: […] This type of realism demonstrates a gift for the patient observation of characters and surroundings, and an attraction towards the more unvarnished, marginal or muted aspects of reality” (Ioniță 2015, 176). This emphasis on realism is understandable if we take into consideration the metaphorical-allegorical character of Romanian cinema in the 80s and 90s, compared to which it is certainly realism that strikes the viewer when watching the films produced after 2000. However, one of the main motifs leading to this paper was a drive to leave behind and to transcend the discourse of realism on Romanian cinema for two obvious reasons. If we use realism for the whole New Wave, either we have to enlarge the meaning of the term beyond acceptable limits and thus make its informative value loose; or we have to make the differences between filmmakers disappear.

Though most critics and scholars agree that besides some similarities, the cinema of Corneliu Porumboiu represents something completely different from other directors of the Romanian New Wave (cf. the famous debate between Andrei Gorzo and Alex Leo Șerban in Dilema Veche[2]), they still have difficulties in leaving the terminology and the theories of realism behind. Andrei State also acknowledges that Porumboiu’s cinema differs from the approach of other Romanian directors, but still analyses his works within the paradigm of realism: “his most important characteristic is formal innovation, a continuous experimentation with different forms of realism” (State 2014, 79. Translated by me, Zs. Gy.). He even identifies three forms of realism in Porumboiu’s films: situational realism being the dominant form of 12:08 East of Bucharest (A fost sau n-a fost?, 2006), semantic realism being the core approach of Police, Adjective (Polițist, adjectiv, 2009), and conceptual realism being in the centre of When Evening Falls on Bucharest or Metabolism (Când se lasă seara peste București sau metabolism, 2013) and The Second Game (Al doilea joc, 2014). (State 2014, 80–87)

Instead of continuing this discourse on realism, I will argue that Porumboiu is not a realist filmmaker, he is just theorising the possibilities of realism, especially of the filmic representation of reality. In this regard I consider that Porumboiu’s films should be interpreted as what Edward S. Small calls “direct theory” in relation to experimental cinema: as films that actually do theory through moving images (Small 1994). Porumboiu’s digression from the mainstream of the Romanian New Wave and the outstanding complexity of his cinema is also proven by the way in which his work became an integral part of theoretical discourses where it is analysed in the broader context of contemporary world cinema.[3]

Text and Image

When analyzing the discursive characteristics of images and the pictorial characteristics of texts, W. J. T. Mitchell in his book entitled Picture Theory introduces two important terms: “metapicture” and “imagetext.” However, the goal of his inquiry is not the comparison of literature and painting, rather he focuses on the cooperation of images and texts in such hybrid genres as illustrated books, comic books, films or theatre. In the case of film – he argues – the image–text relation is not a merely technical question, “but a site of conflict, a nexus where political, institutional and social antagonisms play themselves out in the materiality of representation.” (Mitchell 1994, 91) So, according to Mitchell, the real issue here is not the difference between words and images, but what difference these differences and similarities make – for example how their use will affect the selection of future spectators based on their social status, and so on. His approach led me to the idea that it is worth discussing Porumboiu’s cinema from the perspective of the relation of verbal and visual expression. Police, Adjective, for instance, is not a film about the verbal or visual nature of the filmic expression, but rather about the role of images and texts in processing, interpreting and sharing everyday experiences (as in the scenes where Cristi, the protagonist tries to understand and then to communicate what he actually perceives).

When arguing about the imagetext, Mitchell states that we have to “approach language as a medium rather than a system” (Mitchell 1994, 97), which might open the possibility to analyse verbal communication not as a closed system governed by predefined rules, but rather as a specific kind of “material social practice” (Mitchell 2005, 203). Furthermore, if we accept that there is no such thing as pure verbal or pure visual expression, not even in the case of the typical example of modern abstract painting, then we can speak of intermedial relations not only in the case of media generally considered being hybrid (like cinema, theatre, comic books). This approach – Mitchell continues – “[…] also permits a critical openness to the actual workings of representation and discourse: […] the starting point is with language’s entry into (or exit from) the pictorial field itself, a field understood as a complex medium that is always already mixed and heterogeneous, situated within institutions, histories and discourses: the image understood, in short as an imagetext.” (Mitchell 1994, 97–98) According to him, the term “imagetext” is useful because it makes possible to analyse effects and meanings that would not be visible if we regarded a discourse solely as text or image.

The second term coined by Mitchell is “metapicture,” and in his theory it is similar to metalanguage. By creating the term, he asks if image is capable of grasping its own functioning in the same way as language. After analyzing different images, he concludes that “pictorial self-reference is, in other words, not exclusively a formal, internal feature that distinguishes some pictures, but a pragmatic, functional feature, a matter of use and context. Any picture that is used to reflect on the nature of pictures is a metapicture.” (Mitchell 1994, 56–57) Velazquez’s famous Las meninas (1656) is a paradigmatic example for Mitchell who argues that it was Foucault who made it from a “simple” masterpiece of art history into a real metapicture through questioning the identity of the spectatorial position.

In the following I will try to perform a similar analysis on Porumboiu’s cinema: I will consider it as a metapicture. Regarding the spectatorial position, it is interesting to observe that in Police, Adjective there is a similar approach to the way in which Velazquez included the objects and the subjects of the gaze (that is, the royal couple) into the picture. Analyzing the scenes of trailing and stakeout, we may observe that even when we first get the impression of watching a POV shot belonging to Cristi, after a few moments he enters the frame, thus highlighting the difference between the spectator of the film’s diegetic reality and that of the filmic image, and cancelling the visual identification of the spectator’s point of view with that of the protagonist.

Metapictures, according to Mitchell, are not a subgenre within fine arts, but a fundamental and inherent potentiality of visual representation. The metapicture “is the place where pictures reveal and ʽknow’ themselves, where they reflect on the intersection of visuality, language, and similitude, where they engage in speculation and theorising on their own nature and history.” (Mitchell 1994, 82) The main question, in my view, is not whether Porumboiu’s films can be regarded as metapictures (because, as we have seen, according to Mitchell any image can be used as such), but rather if they reach the complexity one can find for instance in Magritte’s paintings.

Maria Ioniță, in her remarkable paper on Porumboiu, starts her analysis with two Magritte paintings that on the one hand question the visual representability of reality and on the other hand reveal the fundamental incompatibility of the visual and the linguistic. She argues that in a similar way to Magritte, the first two films of Porumboiu (her paper was written in 2010, so no later films could be included) “represent a deliberate exploration of the limits of cinematic realism and a polemic engagement in cinema’s ability to present an objective snapshot of the real.” (Ioniță 2015, 173–174) One important feature of Porumboiu’s cinema – which also uses long takes like Mungiu or Muntean – is that here everything takes place outside of the frame: the revolution in 12:08 East of Bucharest, the drug dealing of the teenagers in Police, Adjective, the shooting of the film within the film in Metabolism, and finally the actual discovery of the treasure in The Treasure (Comoara, 2015). “All that is left in the frame is a sense of form and organization – an apparently accurate rendition of reality from which meaning has been somehow excised: a pipe which is not a pipe.” (Ioniță 2015, 178)

Foucault in his famous paper entitled This is Not a Pipe argues that Magritte’s painting La trahison des images (1928-29) can be understood through the analysis of the peculiar phenomenon of the calligram. “The calligram uses that capacity of letters to signify both as linear elements that can be arranged in space and as signs that must unroll according to a unique chain of sound. […] Thus the calligram aspires playfully to efface the oldest oppositions of our alphabetical civilization: to show and to name; to shape and to say; to reproduce and to articulate; to imitate and to signify; to look and to read.” (Foucault 1983, 21) We can draw the conclusion that Magritte’s strategy of bringing the relation of the verbal and visual representation into focus is based on the derailment of the functioning of the two systems of significance. According to Mitchell, La trahison des images is a third order metapicture, where “it isn’t simply that the words contradict the image, and vice versa, but that the very identities of words and images, the sayable and the seeable, begin to shimmer and shift in the composition, as if the image could speak and the words were on display.” (Mitchell 1994, 68)

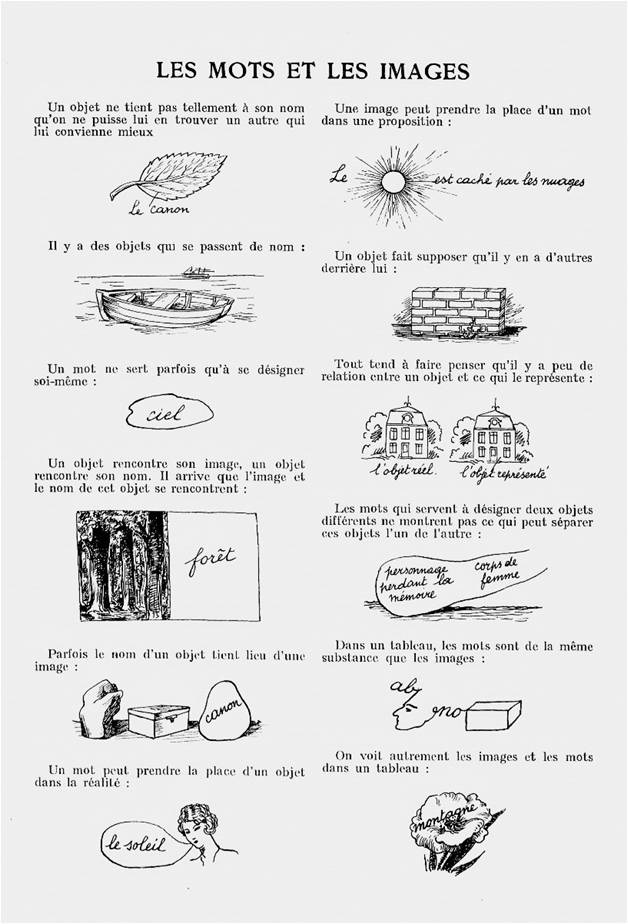

Therefore when Cristi in Police, Adjective reaches out for the limits of written and visual communication and acknowledges the incompatibility of the two, he in fact faces the modernist problem of (visual) representation. Only that his conclusion is somehow opposite to that of Magritte, who in the 12th issue of the journal La Révolution surréaliste published a kind of visual dictionary through which he argued that in visual representation the images are as arbitrary as the linguistic signs and the material of (written) words and images is identical (Magritte 1929).

The detective of Porumboiu’s film, however, believes in the authenticity of his direct (visual) experience, but, with his limited verbal means, he is incapable of grasping his uncertain feelings and intuitions based on his direct, unrepresented experience of the events. For him, until the last scene of the film, the real chasm is between reality and its representation in a pre-established signification system.

Porumboiu’s semiotic inquiries

In order to contextualise Porumboiu’s reflections on representation we need to take a short semiotic and hermeneutic detour. As Mitchell also puts it, the central anomaly of semiotics is the icon (Mitchell 2013, 63), the most problematic element in Peirce’s taxonomy of signs. Without going into details, we only point out that the most important statement of semiotics regarding visual and verbal signs is related to the arbitrary, unmotivated nature of (symbolic) signs (that is, the lack of genuine connection between signified and signifier – Saussure 1959, 67-70) compared to the image that is closely affected by the thing it represents. When analyzing a Panzani commercial, Roland Barthes argues that if we remove all verbal signs from it, we will remain with a message that uses signs which are not originated in any institutionalised set of signs, and thus we get to a paradoxical “message without a code.” These messages, says Barthes, and in fact

all images are polysemous; they imply, underlying their signifiers, a ‘floating chain’ of signifieds, the reader able to choose some and ignore others. Polysemy poses a question of meaning and this question always comes through as a dysfunction […]. Hence in every society various techniques are developed intended to fix the floating chain of signifieds in such a way as to counter the terror of uncertain signs; the linguistic message is one of these techniques. […] The denominative function corresponds exactly to an anchorage of all the possible (denoted) meanings of the object by recourse to a nomenclature. […] When it comes to the ‘symbolic message’, the linguistic message no longer guides identification but interpretation, constituting a kind of vice which holds the connoted meanings from proliferating. (Barthes 1987, 38–39)

In Police, Adjective the protagonist when writing his reports is forced to fix the proliferating polysemic connotations of his direct experience within the precise grammar and vocabulary of the judicial language. This process becomes even more evident later, when his superiors (first the prosecutor, than the commander) make him precisely define the meaning of the words he is using. If we are to apply Barthes’s analysis to the problematics exposed in Police, Adjective, we should replace the image (and especially photography) with direct experience and observation – which is of course recorded and transmitted to us via moving images that – as we have pointed out earlier – do not represent Cristi’s exact view of the events. The transfer here does not take place between images and texts, but between the real and its representation.

In his next movie, Metabolism, Porumboiu pushes this idea even further. It is a scientific image, an endoscopy lacking all stylistic and conventional artistic features (in other words: pre-established signification rules) that is used to illustrate the difference between two kinds of interpretations of an image.

The physician invited by the producer to analyze the recording of the endoscopy performs a professional medical analysis looking only at the images themselves, without paying too much attention to the missing verbal codes that should identify the patient and the medical office. Only afterwards, through the verbal comments of the producer it becomes clear to us that this is a forged endoscopy: an image that is completely misleading, if one ignores the anchoring function of the linguistic signs attached to it. The producer, who is the director’s superior (this aspect will be developed later on), does exactly what Barthes described as the fixing of the “floating chain of signifieds.”

According to Gadamer, there are two extremes of representation, the sign and the symbol between which every form of representation can be identified. “The essence of the picture is situated, as it were, halfway between two extremes: these extremes of representation are pure indication (Verweisung: also, reference), which is the essence of the sign, and pure substitution (Vertreten), which is the essence of the symbol. There is something of both in a picture.” The sign completely effaces itself in order to indicate something else: “It should not attract attention to itself in such a way that one lingers over it, for it is there only to make present something that is absent and to do so in such a way that the absent thing, and that alone, comes to mind.” Unlike the sign, the symbol does not only indicate or refer, but also represents in the sense that it makes present something that is not here: “Thus in representing, the symbol takes the place of something: that is, it makes something immediately present.” (Gadamer 2004, 145, 147)

As we see, for Gadamer picture is situated between these two extremes in the sense that it is capable of indicating something, but in a certain way it also stands in the place of the represented thing. As he argues, “the picture points by causing us to linger over it, for […] its ontological valence consists in not being absolutely different from what it represents but sharing in its being. […] The difference between a picture and a sign has an ontological basis. The picture does not disappear in pointing to something else but, in its own being, shares in what it represents.” (Gadamer 2004, 146)

Though acknowledging its revelative characteristic, I would argue for a different schema of the three elements of representation, where the two extremes would be the sign – that is, complete indication and self-deletion – and the picture that invites us to linger over it, that is capable of conveying something about the represented without “sending us away” from the picture itself. In my view, the antithesis of complete self-deletion and indication is the emphasised “lingering over”, the attraction of attention towards itself – which is the definition of the picture, according to Gadamer. In this schema symbol is to be found in the middle, for its appearance has a certain informative value in itself but its ontological status is still strictly connected to the thing it is standing for. This structure can also be argued for by looking at the arbitrariness of representation: the complete freedom of choice in the case of signs is opposed to the close relation of the picture to the pictured thing. Symbol is to be found in the middle in this respect too, because though there is a certain arbitrariness in choosing the symbols, a kind of analogous relation and a fidelity to traditional symbolic representation is always present.

Cristi’s main dilemma in Police, Adjective is how to translate the undefined visual and direct experience into the conventionalised system of language. And this is the angle from which the scene of the song analysis gets great significance. As the silly pop song makes the protagonist nervous, his wife tries to explain that the lyrics of the song might sound silly, but she just discovers images in it, and she argues that the song tries to define love with the help of symbols. In this situation Cristi takes on the same role his bosses will play opposing him a little bit later, and he asks for precise definitions: are these pictures or symbols? The wife continues that these are images that have become symbols – in other words, pictures that, when included in a conventionalised communication system, have lost their iconic characteristics, because for the purpose of the song it is completely irrelevant what the sea or the meadow mentioned in the text actually look like. Based on this scene, we could argue that Porumboiu’s main dilemma is related to the in-communicability of images: neither the wife, nor Cristi himself is able to adequately communicate the non-verbal experience of reality. He is less concerned with the inadequacy of image and reality, and more with the fact that images or visual experiences are not shareable.

At the end of his struggle with the translation of the visual experience of the observation to the verbal system of the institution Cristi is forced to accept an in-between compromise. In the last scene he is compelled to draw the map of the police raid. If we are to find its place in the aforementioned re-configured Gadamerian schema, the map is a symbol that stands between sign and image, as it uses both visual (iconic) and verbal (conventional) elements. Thus, the compromise occurring in the narrative is reflected in the choice of the form of representation.

In The Treasure the interpretation of the diagram of the metal detector can also be interpreted as a symbolic representation to be found somewhere between sign and image. The diagram is a specific kind of image because, though the colours and forms drawn on the monitor are conventionalised signs, the image is connected in a strictly indexical way to the reality it represents. The fact that in The Treasure the protagonists are analyzing and interpreting the signification systems of different metal detectors in long scenes, clearly shows the director’s strong interest in intermediality. His characters in his other films also seem to be stuck between the possibilities and the limits of expression of different media: the detective in Police, Adjective is to be found between visual observation and textual description, whilst the director of Metabolism between film and its rehearsal.

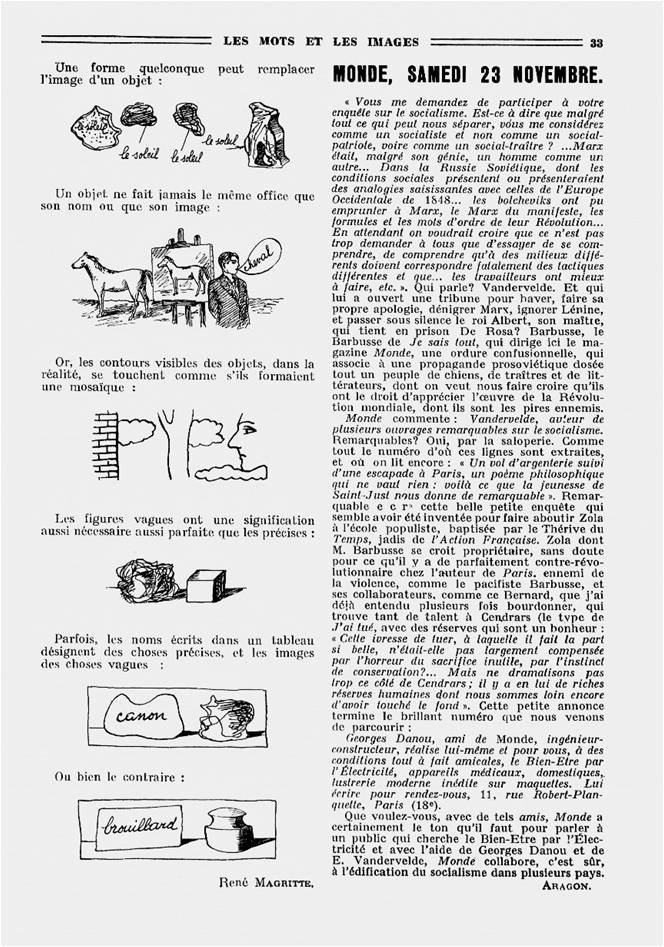

In this latest film the completely untrustworthy nature of verbal, iconic and symbolic signs is finally revealed by the fact that the myth of the treasure buried before the Second World War, which initiated the whole quest in the first place, is simply incoherent with the Mercedes stocks from 1969 that were finally found. Though the treasure actually exists, its representation in the collective memory of the family is completely false. The last twist in this web of intermedial plays is that at the very end of the film, in order to make the story of the treasure credible for the children, the father transforms the signs of wealth (that is, the stocks) into an image (jewellery), creating a new type of representation.[4]

Mediated Reality

The problem of writing, its relation to the spoken text and finally to meaning represents another issue tackled by Porumboiu’s cinema. Mitchell points out that in medieval illustrated manuscripts the dialogues do not emerge from the mouth of the characters (as in modern comic books), but from the gesticulating hands – thus emphasising the primordial difference between written and spoken linguistic expression. He argues that “the medium of writing deconstructs the possibility of a pure image or pure text […]. Writing, in its physical, graphic form, is an inseparable suturing of the visual and the verbal, the ‘imagetext’ incarnate.” (Mitchell 1994, 95) If we are to consider the written text as imagetext, it should be interpreted both as an image, that is capable of revealing something about the represented through its formal characteristics, and as an arbitrary sign that is simply indicating a pre-established set of meanings.

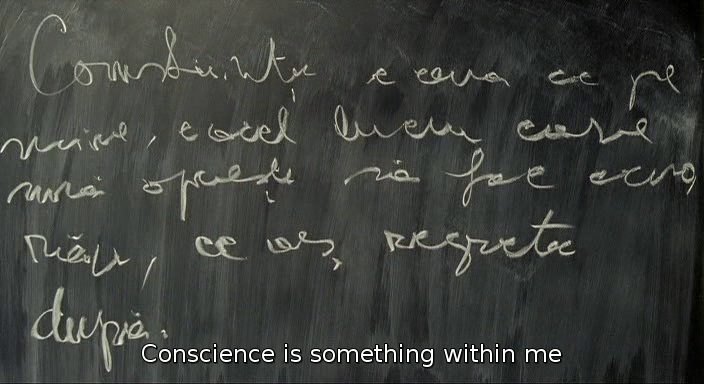

This problem is evidently exposed in Police, Adjective by the fact that, though Cristi writes his reports by hand, the commander asks in the end for the printed dictionary that becomes the site of institutionalised meaning as opposed to the vague nature of personal experience. In this regard, it is of utmost importance that Cristi’s vague definition written by hand on the blackboard takes up at a certain point the whole surface of the image. Here the form of the handwriting gets the same kind of significance as in Magritte’s La trahison des images, where Foucault’s analysis pointed out the image-like nature of the childish handwriting (Foucault 1983, 25).

In his third feature (Metabolism), Porumboiu explores the classical problem of the relation of form and content. All the scenes of the director and his actress/lover evolve around one issue: is there a strict connection between the inner “essence” and the expression that makes it perceivable, visible? This issue is in the middle of all discussions, be that about the difference of digital and celluloid film, the use of forks and knives or chopsticks in European or Asian cuisine, the possibility of Alina being taken as an authentic French actress in France, and so on. In this respect the scene from the beginning of the film is especially meaningful: the director lies to his producer about being ill and during the telephone conversation he presses a spoon to his stomach just to create the pain he verbally represents.

Magritte is invoked in Metabolism too, in the scene where during a rehearsal the director stands in a door frame turning his back towards us in the same way as the mirrored figure of Magritte’s painting, La reproduction interdite (1937). Though the original of the mirrored figure, which is present in the foreground of the painting, cannot be seen in the film, we know that there is a director watching this image from the set from a similar position. Thus the events of the film, the film within the film and the film we are watching are superimposed in a similar way to a palimpsest. To make this medial reflection even clearer, in a later scene Paul turns a video projector directly towards us (and toward the camera recording this scene) to watch the footage from the previous day. When the projection starts, the camera of the film we are watching (Metabolism) becomes the screen for the film within the film – thus, against all conventions of the cinematic apparatus, the film does look back onto its spectator, and the role of the observer and of the observed gets swapped for a short instant.

Perception, Experience and Expression

Cristi’s struggle to express his experiences in Police, Adjective, as we have pointed out above, leads us to one of the main questions of phenomenology. As László Tengelyi explains, Husserl is concerned with the relationship of the perceptual experience and its expression, when he talks about an apparent contradiction. First he argues that even the simplest perception of an object contains a categorical surplus of meaning, that is, something that goes beyond the simple apperception of the object lying ahead of us. From the other perspective, however, Husserl also acknowledges that every linguistic phrase contains a surplus of meaning compared to the appearing object (Tengelyi 2007, 49). This means that the word and the appearance of the object it describes overlap only partially. Drawing on Husserl, Tengelyi argues for the understanding of the experience “as an event in which new meaning emerges by itself.” (Tengelyi 2007, 345. Translation by me, Zs. Gy.) However, he adds that “in the life of human beings experience without expression, language and concept does not occur. This, however, does not change the fact that experience contains a surplus of meaning compared to the linguistic meanings that express it and that, by their own nature, can never be perfectly fitted to it. That is why they can never be brought in perfect overlapping with it.” (Tengelyi 2007, 347) This lack of perfect overlapping is expressed through the story of Cristi in Police, Adjective.

The same issue is discussed from a different angle and with a different conclusion by Merleau-Ponty regarding the interconnected nature of expression and the expressed. He argues in Phenomenology of Perception (1981) that the things perceived by human consciousness cannot be divided into two separate entities (their objecthood and their meaning), as objects are given to me together with their meaning. In the same way as my bodily habits and gestures cannot be dealt with independently from their meaning, language cannot be regarded as a signification system without a meaning. In his view it is unacceptable to consider that there is such a thing as unexpressed thought and meaningless word which are later connected through some kind of conventional system.

In the first place speech is not the ‘sign’ of thought, if by this we understand a phenomenon which heralds another as smoke betrays fire. […] The word and speech must somehow cease to be a way of designating things or thoughts, and become the presence of that thought in the phenomenal world […]. Thought is no ‘internal thing, and does not exist independently of the world and of words. […] Thought and expression, then, are simultaneously constituted, when our cultural store is put at the service of this unknown law, as our body suddenly lends itself to some new gesture in the formation of habit. The spoken word is a genuine gesture, and it contains its meaning in the same way as the gesture contains it. (Merleau-Ponty 1981, 181–183)

If we apply this to Porumboiu’s cinema, first we have to assess the detective’s communication issues in Police, Adjective. Cristi has a certain experience of the events that occur to him together with a specific meaning and significance, based on which he considers that the youngsters should not be punished. What the police commander does is trying to separate the objecthood of the events from their meaning in order to get an “objective” view of the facts. But in reality he does not present the pure facts freed from all meaning and interpretation, instead he links these facts to his own language and terminology, thus proving to us that Merleau-Ponty was right: things are always given to us in perception together with their meaning, and the word does not only designate the thing, the object itself, but in the same moment it brings this meaning into play.

Maria Ioniță’s take on the issue of perception revolves around the comparison of vision and language, as she contends that in Police, Adjective “in the absence of vision, words take over” – even though the protagonist, as his reaction to his wife’s song analysis shows, is sceptical towards the expressive power of language. This is how “the trajectory of Police, Adjective goes from subjective vision (inaccessible to the audience), to traces of this vision (Cristi’s stakeouts), to poetic language mixed with music, which still maintains a certain flexibility, as well as the promise of some sort of vision […], to handwritten reports (a subjective attempt at reducing a subjective vision), to printed language – the dictionary in which the rigidity of words eliminates any need for the real”, and finally the film ends with the sublimation of reality into the abstract code of the map (Ioniță 2015, 180–181).

Institutionalised meanings

The social and political aspect of mediality is discussed by Porumboiu from the perspective of institutions that are empowered to define the rules of representation. Porumboiu’s most important question is quite different from that of Goodman or Gombrich who both questioned the capacity of representation to represent reality, and were keen to define the rules that make perceivers interpret these images, symbols or texts as representations of reality (Mitchell 1994, 329–344 and 345–369). Porumboiu does not believe in the existence of such rules anymore: he is much more interested in those collective or individual institutions that are considered by society, or at least by a smaller group of people, as instances that can define the precise relationship between signs and reality. Referring to the closing scene of Police, Adjective, Andrei State argues that “the fight is won not by the one who masters the language, but by the one who is in the position to impose the rules of the language game. Cristi loses […] not due to his verbal incompetence, but because from the moment he accepts the grammar of the law, he is not able to modify its rules anymore”. (State 2014, 85. Translation by me, Zs. Gy.) Cristi will have to accept the compromise we have presented above because he does not hold a position that is empowered to control the rules of signification: he cannot present a counter-institution to the dictionary used by the commander. Andrew Sarris seems to draw a similar conclusion in his review of the film, claiming that the endgame “contains a parable of society’s mechanisms designed to bring all its citizens to heel.” (Sarris 2009, 14) Thus, an argument on the semantic definition of words is transformed by Porumboiu into an analysis of social relations, and especially of the way in which those of higher ranks are able to exercise their power through the control of interpretation, without being forced to apply traditional coercive measures. Finally, we have to take note of the fact that the roots of Cristi’s attitude lie deeper, as he is simply unable to contextualise individual situations, like when in his argument with his wife he is not willing to accept that the Romanian Academy has the right to change the rules of orthography.

Due to its self-referential layer, the question of the role of the film director in Metabolism is, from a certain perspective, even more sensitive than that of the commander in Police, Adjective. In his interactions with the actress it is always Paul who leads the communication process, defining the timing, the site and the structure of the rehearsals, and he also conducts the private discussions, including those that tackle intimate sides of Alina’s personality. However, Paul finds himself in a different position in his relation to his producer, as she does not believe his story without evidence, and asks for the recording of the endoscopy. Though apparently the director can finally save face by forging a recording, it is clear to us that the producer, who defined the rules of the language game, does not believe him. Paul might have won the battle, but he most probably will not get away next time.

Another aspect of the same issue of hierarchical positions is brought up in The Treasure, where it is the operator of the metal detector who could be the key player in the semiotic game. However, due to his incompetence he has to divulge the signification system of the tools and thus makes himself dispensable. It is not by accident that the two protagonists will finally find the treasure exactly in the same spot where the owner of the property thought it was from the beginning, as if suggesting that the input of the metal detector was more or less irrelevant.

All these examples point out that according to Porumboiu the power over the signification system is the most important element of any communication. If one can define the grammar of communication, he/she can control the possible set of meanings that can be articulated through that semantic system.

On the preceding pages I have presented several theoretical discourses that seem to be relevant in discussing Corneliu Porumboiu’s cinema, and I’ve linked them to the close analysis of the films. My goal was twofold: firstly, I wanted to prove that Porumboiu’s cinema can be more adequately analyzed without the restricting terminology of realism and realist filmmaking that is most commonly associated with the Romanian New Wave. Secondly, I wanted to show that his films can also be considered direct theories (as defined by Edward Small) in the sense that the films are capable to discuss theoretical issues through their narrative and visual composition. For this purpose I built the discussion around five major topics: I have analyzed the relation of text and image; the interconnected nature of signs, images and symbols; the mediated nature of representation or the classical problem of form and content; the perceptual experience and its shareability; and finally the political role of institutionalised meanings.

References

Barthes, Roland. 1987. Rhetoric of the Image. In Image, Music, Text, ed. Stephen Heath, 32–51. London: Fontana Press.

Foucault, Michel. 1983. This Is Not a Pipe. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gadamer, Hans-Georg. 2004. Truth and Method. 2nd ed. Continuum Impacts. London; New York: Continuum.

Gorzo, Andrei. 2009a. Despre îndrăzneala lui Poliţist, adjectiv (1). Dilema veche, nr. 279, 18th June 2009.

http://agenda.liternet.ro/articol/9406/Andrei-Gorzo/Despre-indrazneala-lui-Politist-adjectiv.html. Last accessed 06. 06. 2016.

Gorzo, Andrei. 2009a. Despre îndrăzneala lui Poliţist, adjectiv (1). Dilema veche, nr. 279, 18th June 2009. http://agenda.liternet.ro/articol/9406/Andrei-Gorzo/Despre-indrazneala-lui-Politist-adjectiv.html. Last accessed 06. 06. 2016.

———. 2009b. Despre îndrăzneala lui Poliţist, adjectiv (2). Dilema veche, nr. 280, 28th June 2009. http://agenda.liternet.ro/articol/9406/Andrei-Gorzo/Despre-indrazneala-lui-Politist-adjectiv.html. Last accessed 06. 06. 2016.

———. 2009c. Despre îndrăzneala lui Poliţist, adjectiv (3). Dilema veche, nr. 281, 5th July 2009. http://agenda.liternet.ro/articol/9406/Andrei-Gorzo/Despre-indrazneala-lui-Politist-adjectiv.html. Last accessed 06. 06. 2016.

Ioniță, Maria. 2015. Framed by Definitions. Corneliu Porumboiu and the Dismantling of Realism. In European Visions: Small Cinemas in Transition, eds. Janelle Suzanne Blankenship and Tobias

Nagl, 173–86. Bielefeld: Transcript.

Magritte, René. 1929. Les mots et les images. La Révolution surréaliste, no. 12 (December). http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k58451673.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 1981. Phenomenology of Perception. London: Routledge.

Mitchell, W. J. T. 1994. Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation.Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

———. 2005. What Do Pictures Want? The Lives and Loves of Images. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

———. 2013. Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Pethő, Ágnes. 2015. Between Absorption, Abstraction and Exhibition: Inflections of the Cinematic Tableau in the Films of Corneliu Porumboiu, Roy Andersson and Joanna Hogg. Acta Universitatis

Sapientiae, Film and Media Studies, no. 11: 39–76.

Sarris, Andrew. 2009. The Uncertainty Principle. Corneliu Porumboiu and the Romanian Resurgence. Film Comment, no. November-December: 14.

Șerban, Alex. Leo. 2009. Despre realismul lui Poliţist, adjectiv (scrisoare pentru Andrei

Gorzo).” Dilema veche, nr. 285, 29th July 2009. http://agenda.liternet.ro/articol/9531/Alex-Leo-Șerban-Andrei-Gorzo/Despre-realismul-lui-Politist-adjectiv-scrisoare-pentru-Andrei-Gorzo.html Last

accessed 06. 06. 2016.

Small, Edward S. 1994. Direct Theory: Experimental Film/video as Major Genre.Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

State, Andrei. 2014. Realismele lui Corneliu Porumboiu. In Politicile filmului: contribuţii la interpretarea cinemaului românesc contemporan, eds. Andrei Gorzo and Andrei State, 73–87. Cluj-

Napoca: Tact.

Tengelyi, László. 2007. Tapasztalat és kifejezés. Budapest: Atlantisz.

[1] This work was supported by the project entitled Space-ing Otherness. Cultural Images of Space, Contact Zones in Contemporary Hungarian and Romanian Film and Literature (OTKA NN 112700).

[2] The first three articles by Gorzo describe how Porumboiu defies the rules of conventional filmic language, reaching an “anti-spectacular realism” (Gorzo 2009a, b, c). In his answer, Alex Leo Șerban argues that while he agrees that Police, Adjective is an important film for Romanian cinema, in his view this is not due to its realism. (Șerban 2009).

[3] Cf. Ágnes Pethő’s paper, where focusing on the cinematic tableau, she compares Porumboiu’s cinema to that of Roy Andersson and Joanna Hogg (Pethő 2015).

[4] This transfiguration is backed up by the narrative of the film through several scenes where the father reads the tale of Robin Hood to his son.