Eszter Ureczky

Crises of Care: Precarious Bodies in Western and Eastern European Clinical Film Dystopias[1] (download pdf)

Abstract: Several recent clinical films have problematised the socio-medical and psychological aspects of the contemporary first world culture of wellness and healthism: The Road to Wellville (Alan Parker, 1994), Hotel Splendide (Terence Gross, 2000), Youth (Paolo Sorrentino, 2015), A Cure for Wellness (Gore Verbinski, 2016); Lunacy (Síleni, Jan Svankmajer, 2005), Johanna (Kornél Mundruczó, 2005), Pál Adrienn (Ágnes Kocsis, 2010), Godless (Bezbog, Ralitza Petrova, 2016) and Scarred Hearts (Inimi cicatrizate, Radu Jude, 2016), which are all set in closed medical institutions designed to rejuvenate or heal their patients/guests, where the protective but at the same time claustrophobic and disciplining microcosm of the hotel/sanatorium/hospital appears as a carefully monitored, safely contained counter-space of external (social) and internal (bodily) risks. As Michel Foucault argues, the disappearance of bedside medicine and the “sick man” after the Enlightenment era was followed by the emergence of hospital medicine and the patient in the 19th century (Foucault 1963), and it seems that the 20th century witnessed the births of the wellness guest and the care home inmate in an increasingly medicalised, somatised and normalised world. On the basis of this insight, the present paper aims to position the chosen clinical films along a biopolitical trajectory of care, outlining the emergence of 21st-century notions of health and precarious embodiment in Western and Eastern European cultural scenarios.

Keywords: biopolitics, medical humanities, care, precarity, Eastern Europe, clinical film

The Crisis of Care in Cinema

Several recent clinical films have problematised the socio-medical and psychological aspects of the contemporary first world culture of wellness and “healthism”: The Road to Wellville (Alan Parker 1994), Hotel Splendide (Terence Gross, 2000), Youth (Paolo Sorrentino 2015), A Cure for Wellness (Gore Verbinski, 2016); Lunacy (Síleni, Jan Svankmajer 2005), Johanna (Kornél Mundruczó, 2005), Adrienn Pál (Pál Adrienn, Ágnes Kocsis, 2010), Godless (Bezbog, Ralitza Petrova, 2016) and Scarred Hearts (Inimi cicatrizate, Radu Jude 2016). All are set in closed medical institutions designed to rejuvenate or heal their patients/guests, where the protective but at the same time the claustrophobic and disciplining microcosm of the hotel/sanatorium/hospital appears as a carefully monitored, safely contained counter-space of external (social) and internal (bodily) risks. As Michel Foucault argues, the disappearance of bedside medicine and the “sick man” after the Enlightenment era was followed by the emergence of hospital medicine and the patient in the 19th century (Foucault 1963), and it seems that the 20th century witnessed the births of the wellness guest and the care home inmate in an increasingly medicalised, somatised and normalised world. On the basis of this insight, the present paper aims to position the chosen clinical films along a biopolitical trajectory of care, outlining the emergence of 21st-century notions of health and precarious embodiment in Western and Eastern European cultural scenarios.

The cinematic corpus of the study can be characterszed as a spatially focussed selection of clinical dystopias, for they all appear to comment on the present-day biomedical dilemmas of health and disease, normality and pathology as well as youth and ageing within medicalised settings. Some of the films also show a hypotextual and even intertextual connection with Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain (1924), the literary monument of the interwar period’s escapism, some kind of a counter-reaction to the pressures of accelerated modernist production and capitalism, and marked by a turning towards the pathology of slow-paced consumption (in both the medical and economic senses of the word). As opposed to Mann’s image of the utopistic sanatorium, though, the clinical films to be discussed often create dystopic and post-human cinematic spaces to stage the universal precarity of late-modernity and to question the current regime of care within the welfare state – from which there seems to be no escape. By examining the clinical films as dystopic depictions of the current “crisis of care” (theorised by Susan Phillips [1996] and Nancy Fraser [2016]), the paper reads the institutionalised patients as essentially vulnerable bodies by relying on the notion of precarity understood by Judith Butler and Isobell Lorey (2015) as the prime biopolitical condition of today’s advanced societies.

Despite their shared generic background,[2] the somato-spatial politics of Western and Eastern European clinical films show major differences. Western (American, British, German and Italian) works typically problematise wellness culture, ageing and “time poverty” (Fraser 2016) in seemingly utopistic and medicalised scenarios of care, relying on the representation of aestheticised rural institutional spaces, black humour and grotesque bodily imagery. Their settings often come across as uncannily atmospheric sites of a kind of safe timelessness, as if health and care had no actual plot but manifesting as a chronic, vacuum-like condition instead, where resting, that is, the lack of productive labour becomes the ultimate luxury for the citizen guests. Eastern European (Czech, Hungarian, Romanian and Bulgarian) clinical films, on the other hand, are typically set in bleak post-Socialist urban milieus, the dominant biopolitical model of which could be approached by the Agambenian notions of the camp and bare life (1995). The darkly grotesque and melancholic thanatopolitics of these filmic worlds seem to actualise and articulate the harsh reality of the Foucauldian point about the nature of modern biopolitical power, that of “making live and letting die” (Foucault 2003, 241). Thus, these films will be interpreted as examples of a genre one might identify as the Eastern European clinical grotesque.

Healthism in The Road to Wellville, Hotel Splendide, A Cure for Wellness and Youth

If each historical epoch seems to produce its own characteristic “period illness” (Spackman 1989, 32), a malady which breeds discourses that reveal a great deal about the most pressing social anxieties and cultural tensions of the day,[3] then the period illness of the 21st century can be identified as health itself, that is, the biopolitical ideology of healthism, wellness and youthfulness. The various privately managed or state-governed purification and protection rituals first world citizens willingly or forcefully undergo in the name of health are all part of the contemporary civic religion of wellness. Foucault uses the notion of governmentality to denote the structural interconnection between the government of a state and the techniques of self-government in modern Western societies, and wellness as well as self-care seem to be powerful biomedical elements of current forms of governmentality. Still, there is a visible and growing distrust of medical, welfare and other care institutions today as tools of subjection and normalisation, since “increasingly in the helping professions, personhood and caring have been eclipsed by the depersonalizing procedures of justice distribution, technological problem-solving, and the techniques and relations of the marketplace” (Phillips 1996, 2). Foucault also pointed out that “somatocracy” has been taking over the place of a “theocracy” (Adorno 2014, 99) in the West, and the quick rise of biopolitical theory in the humanities also suggests the overwhelming presence of somatic anxiety and security obsession. In the 21st century, the soul is thus more the prison of the (supposedly healthy and cared-for) body than ever.

The films in question all challenge the contemporary notions of health, a concept especially difficult to define either from a medical or a phenomenological point of view. The World Health Organisation’s definition, for instance, is somewhat vague, grasping health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being” (Aho 2009, 14). Immanuel Kant also uses the expression “well-being” to capture the essence of health, claiming that “well-being is not felt for it is the simple consciousness of living” (qtd. in Canguilhem 1991, 243); while Hans Georg Gadamer defines its meaning by the luxury of being able to forget about ourselves: “our enjoyment of good health is constantly concealed from us” (Gadamer 1996, 112). However, the Western history of healthism shows the opposite of this happy non-awareness: a compulsive and anxious consciousness of one’s own embodiment, as The Road to Wellville shows. Alan Parker’s 1994 piece can be viewed as an early example of the filmic representation of healthism, telling the story of the legendary and controversial American expert, Dr Kellogg’s early 20th-century sanatorium, using comical, even slapstick elements to revisit the roots of the present day health craze. The film foreshadows several current conditions related to wellness culture, such as strict dieting (by consuming corn flakes), sexual self-discipline, prevention and risk reduction, for in the contemporary West, as Alison Bashford puts it, “the good citizen is the healthy citizen” (Bashford 2003, 117). Accordingly, notions like Nikolas Rose’s “biological citizenship” (Rose 2007, 132) have started to define available subject positions, as human beings are increasingly coming to understand themselves in somatic terms nowadays, and are ready to become wellness guests to be clean and cared-for citizens as a result.

[Fig.1.] The birth of healthism in America. The Road to Wellville

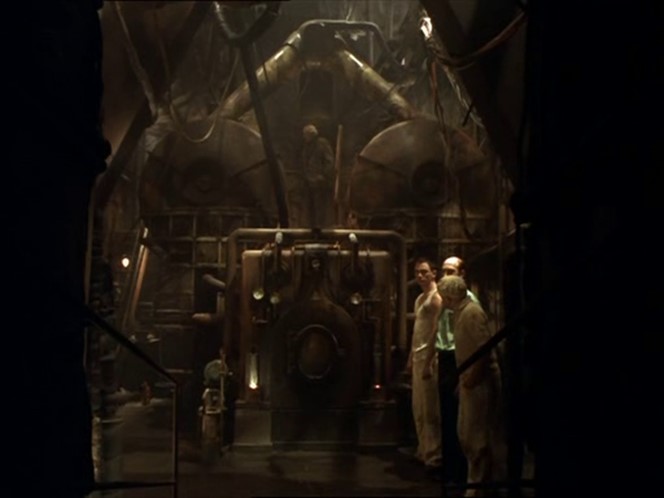

Hotel Splendide, created six years after The Road to Wellville, seems to be the British version of the same story in many ways. This black comedy is set in a family health resort run on a remote island by a family of eccentrics. The guests, typically elderly people suffering from indigestion, are systematically subjected to an unappetizing diet of fish and algae and undergo daily enema treatments. Similarly to Parker’s film, where Dr Kellogg turns out to be a traumatizing and cruel father figure, the oedipal implications of the Freudian family romance are also crucial in Hotel Splendide, as the grotesque health regime and monstrous heating system of the resort were designed by the oppressive mother figure who is already dead. In both films, the obsessive control of the guests’ bodily functions seems to be a parodistic depiction of the modern homo clausus, which can never lose control over its unmentionable parts, and even if such a thing happens, one is expected to attempt to regain control as soon as possible or conceal the damage at all cost. By medicalising non-disease conditions (such as sexual or gastronomic desires), the films also expose the Foucauldian production of docile bodies, which “may be subjected, used, transformed and improved” (Foucault 1979, 136).

[Fig.2.] The monstrous motherly machine. Hotel Splendide

While the two previous films have happy endings and feature a rebellious romantic plotline, A Cure for Wellness marks a turning point in the evolution of the Western clinical film. Gore Verbinski’s 2016 work is an American-German science fiction or psychological horror thriller, which is set in a Swiss health resort led by an insane doctor obsessed with heredity and eternal life, representing plenty of body horror, a hyper-stylised atmosphere of the gothic macabre and, as most critics have pointed out, several plot holes. Partly as a result of the setting, The Magic Mountain becomes not only a hypotext but an intertextual link as well; for instance, one of the male nurses is shown reading Mann’s novel while administering a treatment. The Swiss luxury resort symbolises the present-day endpoint of the evolution of medical spaces: the Foucauldian proto-clinic of the 18th-century was meant to be an unspecialised, collective study of cases, while the nineteenth century hospital became the hygienic space of increasingly taxonomised cases (Foucault 1963, 59-60).[4] The postmodern health resort, however, is aiming to slow down degenerative processes before they even appear, creating a sinister atmosphere of pathological anticipation. Ultimately, instead of the dangerous, potentially infectious patient of the 19th century, now the patient is the one at risk from the “dangerous hospital” (Armstrong 2002, 123) within the biopolitical paradigm of contemporary Western somatocracy.

[Fig.3.] The sinister beauty of the 21st-century Magic Mountain. A Cure for Wellness

Despite its mixed reception, A Cure for Wellness is a symptomatic filmic response to the excesses of contemporary health norms and the all-pervasive power of the medical gaze – both in terms of inner bodily spaces and future temporal planes. The mysterious indigo “vitamin” bottles designed by the doctor protagonist problematise the questions of longevity, incest, eugenics and even the risks of the compulsively capitalist American work ethic,[5] but it poses ageing as the greatest threat to the sexually and economically productive individual. The film’s treatment of ageing addresses current views on old age, such as “ageing is not destruction or degradation, but self-destruction” and that “productivity and profitability required the ‘biopolitical’ cultivation of a healthy body” (Miquel 2015, 199) from the 20th century onwards. The increasing normalising and pathologising of old age also demonstrates the changing role of medicine in the extra-corporeal space of lifestyle as well as prognosis and prevention: “the new late twentieth century medical model – that might be described as Surveillance Medicine” (Armstrong 2002, 110). In this paradigm of healthism, “it was no longer the symptom or sign pointing tantalizingly at the hidden pathological truth of disease within the body, but the risk factor opening up a space of future illness potential” (Armstrong 2002, 110); that is, we live in an era where the medical science of yet unhappened experiences of embodiment rule. This also implies that in what Rose calls the politics of life itself, “biology is no longer destiny […] Judgments are no longer organized in terms of a clear binary of normality and pathology” (Rose 2007, 40).[6] The key to 21st-century destinies seems to be rooted in the problem of self-care.

Youth similarly addresses the problems of ageing and care, but in a more indirect way. Paolo Sorrentino’s 2015 piece is also set in a luxurious Swiss health resort, featuring an elderly composer and other fellow guests (a senior director, a young actor, etc.), pondering upon the dilemmas of lost youth, memory, health, art and love. The film builds rather on tableaux vivants and isolated set pieces than a continuously evolving plot, evoking a strong sense of nostalgia and melancholia. This atmospheric structuring suggests that health or wellbeing have no real plot but they are manifesting themselves as a chronic, timeless condition (both as a state and an illness). Just like in the case of the previous films, the health resort appears as an uncannily heterotopic, idealised but disruptive space functioning along the lines of its idiosyncratic rules. Youth addresses the so-called crisis of care in a complex way, insofar as it is “best interpreted as a more or less acute expression of the social-reproductive contradictions of financialised capitalism” (Fraser 2016, 99).[7] The overworked artistic guests come to the resort to be taken care of, to seek physical and spiritual improvement and inspiration, but the care provided here only makes them face the utter futility and precarity of their supposedly immortal and precious life projects and the unavoidable loss of self and others in the course of living.

[Fig.4.] The melancholy of old age. Youth

Precarious bodies in Scarred Hearts, Lunacy, Johanna, Adrienn Pál and Godless

The Eastern European clinical films to be discussed all emphasise the often very thin borderline between disease and death, not “merely” the issues of health and ageing as the gateways to them, as seen in the previous section. The representation of chronic disease as a source of human agony has not always been a central theme in the arts, as Susan Sontag points out: “the sufferings most often deemed worthy of representation are those understood to be the product of wrath, divine or human. (Suffering from natural causes, such as illness or childbirth, is scantily represented in the history of art; that caused by accident, virtually not at all – as if there were no such thing as suffering by inadvertence or misadventure)” (Sontag 2003, 33). However, several recent Eastern European clinical films seem to focus on the illness experience and the death of their characters to criticise individual and institutional notions of care. If health has been defined above as essentially a lack of an awareness of one’s embodiment, the current cultural treatment of death shows similar signs of a lack of awareness: a desire not having to be conscious of it. As Gadamer claims, one can talk about “an almost systematic repression of death” (Gadamer 1996, 63) today. The modern desacralization of death went hand in hand with its medicalization, and the evolution of civilization has paradoxically led to the inhuman experience of dying, as Norbert Elias puts it: “never before in the history of humanity have the dying been removed so hygienically behind the scenes of social life” (Elias 2001, 23). Scientific and social advancement have thus paradoxically brought about the increasing dehumanization of death as well. Elias actually identifies this high level of biotechnological advancement as a paradoxical civilisational failure of first world countries: “the fact that, without being specifically intended, the early isolation of the dying occurs with particular frequency in the more advanced societies is one of the weaknesses of these societies (Elias 2001, 2).

Scarred Hearts raises the questions of chronic illness, institutionalisation and death at the same time. Radu Jude’s 2016 film is a loose adaptation based on the autobiographical writings of the Romanian writer Max Blecher, who suffered from bone tuberculosis or Pott’s disease. The film is set in a 1930s sanatorium by the Black Sea’s beautiful horizon, which provides a scenic background to the experience of patienthood. Similarly to Youth and A Cure for Wellness, this biopic has a vignette-based structure featuring beautiful open-air scenery. Another connection is the quasi-utopian depiction of the Magic Mountain-like sanatorium as a place of suffering but also pleasure: “This place is like a drug”, as the protagonist puts it. The film relies on black humour and the grotesque as well as a kind of melancholic nostalgia to make a point about living with chronic illness. While Talcott Parsons used the expression “sick role” to explain the expectation that when ill people get well, they should cease to be patients, and return to normal, Arthur W. Frank talks about “remission society” (Arthur W. Frank 1995), where people who used to be patients can get effectively well but still they could never be considered cured. The latter notions seems to be more useful in the protagonist’s case, who does eventually manage to leave the sanatorium, but only on a stretcher to be hospitalised (and die) somewhere else.

[Fig.5.] Evoking The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp. Scarred Hearts

Emmanuel has to spend all his time in bed, cast into a rigid, painful plaster preventing his spine from collapsing, thus his survival is provided by a system that is designed to secure his insecure body, ceaselessly torturing him in the meantime. His horizontal existence in his plaster and his bed, the total lack of agency or privacy also question the ethical responsibility of 20th and 21st-century late capitalism, which is expected to offer a comprehensive sense of safety to its citizen-consumers along with the right of isolated individualism. As Slavoj Žižek argues: “this is emerging as the central »human right« in late-capitalist society: the right not to be harassed, to be kept at a safe distance from others” (Žižek 2004, 508). The film thus seems to pose the question: what is better, healthier then: having the right to be left alone with a dehumanizing disease or having the right to survive even in inhuman conditions? As “chronic illness makes the repression of death anxiety virtually impossible” (Aho 2009, 125), Emmanuel’s story makes the thanatopolitical dilemmas of chronic disease especially tangible for today’s viewers. If “an acceptable death is a death which can be tolerated by the survivors” (Ariés 1974, 89), his treatment in the remote sanatorium makes his death duly distant and thus tolerable for his family. The fact that the protagonist is a poet makes the story a Künstlerfilm as well, powerfully grasping the difference between the medical and phenomenological understandings of the body, that is, the fissure of Körper and the Leib: “the basic unit of analysis in biomedicine is the Körper, a system of chemical (hormonal), electrical (neurological), and mechanical (skeletal) functions. In medical science the corporeal body is both decontextualised (removed from its social-cultural milieu) and de-animated (divested of any semblance of spirit or soulstuff). In other words, it is depersonalized” (Aho 2009, 77). The protagonist’s body becomes especially grotesque as it actually seems to be shown in the act of becoming: becoming a patient, a lover and an even an artist, where the event of death brings nothing to an end in the Bakhtinian sense of the grotesque but becomes part of his bodily and intellectual history.

Grotesque embodiment is also crucial in Lunacy’s representation of not physical but mental illness, as Svankmajer’s work, which is also set in a closed institution, but in this case a mental asylum, is surrealistically blurring the boundaries between patients and doctors. In the film, a man moves in with a mysterious aristocrat and is soon persuaded to enter into an asylum for preventative treatment with him. Eventually, nothing turns out to be what it seems to be, and the mysterious marquis proves to be even more sinister than what the young man assumed. Lunacy combines the medically and culturally constructed notion of madness with a critique of institutionalisation and normalisation, featuring not only physical but mental agony as well. One of the film’s central messages seems to be that the cure can actually be the condition itself, and that the sane objectivity of medicine is often but an illusion.

[Fig.6.] The colours of madness. Lunacy

Johanna represents the precarity of hospital patients and the hospital itself in a similarly recognisably Eastern European scenario, where the medical encounter is also burdened by the hierarchic, patriarchal conditions of post-Socialist cultures. The film tells the story of a young drug addict, who falls into a coma after an accident. The doctors miraculously manage to save her, and then, touched by grace, Johanna cures patients by offering them her body. The head doctor is frustrated by her continued rejection of him and allies himself with the outraged hospital authorities. They fight against her but the grateful patients still decide to protect her. Johanna places special emphasis on the sexuality of suffering bodies, and by doing so connects the disruption of the two major bodily taboos of the recent past: “as, in the 1960s, sexual liberation challenged the taboos around sex so, in the 1990s and in the new millennium, a new movement of ‘death liberation’ has arisen that challenges the taboos around death” (Noys 2005, 2). Johanna is an opera film and thus a musical interpretation of the Passion of Joan of Arc. Thus, the dichotomies of the sacred and the profane, agony and sexuality, pain and pleasure, treatment and miracle, the figures of the angel, the nurse and the prostitute as spiritual, medical and sexual “caregivers” come together in Johanna’s depiction by Christian symbols and medical spaces, subverting all these binary oppositions.

[Fig.7.] The angelic nurse. Johanna

Johanna, Pál Adrienn and the last film to be discussed, Godless, share a major feature in terms of characterisation: they all have dysfunctional female carer figures as their protagonists, as none of them fits the conventional, hygienic and professional image of the Nightingale nurse. The professional and technologised isolating care of bodies is the central theme of Pál Adrienn.[8] The chronic ward appears as the space of posthuman bodies and also marks the logical extreme of the evolution of hospital spaces in the West.[9] Since the history of anatomy shows that medical and foremost upon the inanimate, the living patient is often treated in a cadaverous or machine-like fashion, and this is what the film’s dying patients suggest as well. It also grasps many of the flaws of modern medicine: “depersonalization, overspecialization, the neglect of psychosocial factors in the etiology and treatment of disease – can be traced to medicine’s reliance on the Cartesian model of embodiment” (Leder 1992, 28). However, Piroska, the obese nurse, manages to awake from her “comatose” condition by dissecting her own past and reconnecting with her own body and the one she takes care of.

In this sense, the film poses the present-day problem of precarisation as understood by Judith Butler as a process that produces “insecurity as the central preoccupation of the subject” (Butler 2015, viii). Similarly, Isobell Lorey argues that “contrary to the old rule of a domination that demands obedience in exchange for protection, neoliberal governing proceeds primarily through social insecurity, through regulating the minimum of assurance while simultaneously increasing instability” (Lorey 2015, 2). She adds that “the conceptual composition of ‘precarious’ can be described in the broadest sense as insecurity and vulnerability, destabilization and endanger merit. The counterpart of precarious is usually protection, political and social immunization against everything that is recognized as endangerment” (Lorey 2015, 10-11). According to Lorey’s full definition, “precarity can therefore be understood as a functional effect arising from the political and legal regulations that are specifically supposed to protect against general, existential precariousness. From this perspective, domination means the attempt to safeguard some people from existential precariousness, while at the same time this privilege of protection is based on a differential distribution of the precarity of all those who are perceived as other and considered less worthy of protection” (Lorey 2015, 22). The notions of the crisis of care and precarity seems to grasp the same problem with biopolitical power in the 21st century: the dysfunctional interconnection of social care and individual vulnerability. The crisis of care is thus also embodied by the depiction of uncaring carers in the Eastern European context, which is especially central to the last film to be mentioned.

[Fig.8.] The monitor room. Adrienn Pál

Godless, a recent Bulgarian film represents both of the above dilemmas, even though it is not set in one single medical institution. The film rather follows the daily routine of a caring home nurse, who visits elderly people in a dilapidated countryside town. The town itself appears as a closed, forgotten institution, where the law is entirely corrupt and illegal trading with patients’ ID cards is an absolutely tolerated practice. (In this sense, Ken Loach’s 2016 film, I, Daniel Blake could be read as another filmic reflection on universal precarity.) In this camp-like, corrupt social space there is no real difference between inmates and carers, prisoners and guards, policemen and criminals, they are equally victims of the biopolitical aftermath of state socialism, leading what Agamben would identify as bare lives. In Agamben, the camp is understood as the biopolitical space of modernity as such: “the camp is the space that is opened when the state of exception begins to become the rule” (Agamben 1998, 169), and state order as such can only be born from the enclosed, disciplined, pathologised space of the camp. In Godless, not only the space of the caring home but post-communist society as such appears as a collapsing system producing precarious bodies.

[Fig.9.] The careless carer. Godless

Conclusion: Cultures of Unwellness

Jean Baudrillard in his last, posthumously published book, The Agony of Power articulates the prime ethical task of today’s First World welfare citizen as follows:

we are not succumbing to oppression or exploitation, but to profusion and unconditional care [to the power of those who make sovereign decisions about our well-being]. From there, revolt has a different meaning: it no longer targets the forbidden, but permissiveness, tolerance, excessive transparency – the Empire of Good. For better or worse. Now you must fight against everything that wants to help you. (Baudrillard 2010, 88)

In this passage, Baudrillard describes a kind of utopistic auto-immune reaction within the current biopolitical body of advanced societies, taking the modern project of security, discipline and individualism to its logical extreme: the postmodern collapse of care. What all the films share is the increasingly predominant 21st-century tendency to distrust welfare institutions, security and health services symptomatically represented by the recent upsurge of the above discussed clinical film dystopias, which thematise the crisis of care as well as the anxiety of personalised, institutionalised and precarised wellbeing as the period illness of the post-millennial age: the chronic condition of existential unwellness. This collapse of care, however, shows major differences in contemporary cinema: while in Western European and American examples it is especially ageing and unhealthy lifestyles which become pathologised states to be in, in Eastern European cinema it is unavoidable death, often with indignity, which is situated within an institutional framework of care.

The cinematic representation of precarity also raises several bioethical questions, as it is not only the medical gaze but also the viewer’s gaze which should be problematised. Sontag argues that such a gaze should be sanctioned: “perhaps the only people with the right to look at images of suffering of this extreme order are those who could do something to alleviate it – say, the surgeons at the military hospital where the photograph was taken – or those who could learn from it. The rest of us are voyeurs, whether or not we mean to be” (Sontag 2003, 34). Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, however, suggests the use of the word stare instead of gaze when looking at other people’s disability and bodily pain, and argues for the humanizing power of the Winnicottian holding function: “another psychological dread that staring ignites in the starer is an unsettling awareness of our own embodiment. The denial of death and vulnerability that the ego relies upon to get us through our days depends upon the disappearance of our own bodies to ourselves” (Garland-Thomson 2009, 58). Maybe this is the ethical task of the 21st-century viewer of clinical film dystopias: to stare at the medical gaze in order to (re)humanise it.

References

Adorno, Francesco Paolo. 2014. Power over Life, Politics of Death: Forms of Resistance to Biopower in Foucault. In The Government of Life Foucault, Biopolitics, and Neoliberalism. Eds. Vanessa Lemm and Miguel Vatter. New York: Fordham UP: 98-111.

Agamben, Giorgio. [1995] 1998. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

—. 2015. The Use of Bodies: Homo Sacer IV, 2. Trans. Adam Kotsko. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

Aho, James and Kevin Aho. 2009. Body Matters: A Phenomenology of Sickness, Disease, and Illness. New York, Plymouth: Lexington.

Ariés, Philippe. 1974. Western Attitudes Toward Death: From the Middle Ages to the Present. Trans. Patricia M. Ranum. London: Marion Boyars.

Armstrong, David. 2002. A New History of Identity: A Sociology of Medical Knowledge. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire and New York, N.Y.: Palgrave.

Bashford, Alison. 2003. Imperial Hygiene: A Critical History of Colonialism, Nationalism and Public Health. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Baudrillard, Jean. 2010. The Agony of Power. Trans. Ames Hodges. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).

Butler, Judith. 2015. Foreword. In Isabell Lorey. State of Insecurity: Government of the Precarious. Trans. Aileen Derieg. London, New York: Verso: vii-xi.

Canguilhem, Georges. 1991. The Normal and the Pathological. New York: Zone.

Elias, Norbert. [1985] 2001. The Loneliness of the Dying. Trans. Edmund Jephcott. New York, London: Continuum.

Foucault, Michel. 1963. The Birth of the Clinic: An Archeology of Medical Perception. Trans. A. M. Sheridan. London and New York: Routledge.

—. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. 1979. Trans. Alan Sheridan. New York, NY.: Vintage Books.

—. “Society Must Be Defended”: Lectures at the College de France, 1975-76. 2003. Trans.

David Macey. Eds. Mauro Bertani and Alessandro Fontana. New York: Picador.

Frank, Arthur W. 1995. The Wounded Storyteller: Body, Illness and Ethics. Chicago, London: University of Chicago Press.

Fraser, Nancy. 2016. Contradictions of Capital and Care. New Left Review July, Aug.: 99-117.

Gadamer, Hans-Georg. 1996. The Enigma of Health. Trans. Jason Gaiger and Nicholas Walker. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP.

Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie. 2009. Staring: How We Look. Oxford, New York: Oxford UP.

Gross, Terence. 2000. Hotel Splendide. Canal+.

Jude, Radu. 2016. Scarred Hearts. HI Film Productions.

Király, Hajnal. 2015. A klinikai tekintet diskurzusai a kortárs magyar filmben. Tér, hatalom és identitás viszonyai a magyar filmben. Eds. Zsolt Győri and György Kalmár. Debreceni Egyetemi Kiadó: 202-215.

Kocsis, Ágnes. 2010. Pál Adrienn. KMH Film.

Leder, Drew, ed. 1992. The Body in Medical Thought and Practice. Springer-Science+Business Media, B.V..

Lorey, Isabell. 2015. State of Insecurity: Government of the Precarious. Trans. Aileen Derieg. London, New York: Verso.

Miquel, Paul-Antoine. 2015. Ageing and Longevity. The Care of Life: Transdisciplinary Perspectives in Bioethics and Biopolitics. Eds. Miguel de Beistegui, Giuseppe Bianco and Marjorie Gracieuse. London, New York: Rowman & Littlefield: 199-210.

Mundruczó, Kornél. 2005. Johanna. Proton Cinema.

Noys, Benjamin. 2005. The Culture of Death. Oxford, New York: Berg.

Parker, Alan. 1994. The Road to Wellville. Beacon Communications.

Petrova, Ralitza. 2016. Bezbog. Klas Film.

Phillips, Susan S. 1996. The Crisis of Care: Affirming and Restoring Caring Practices in the Helping Professions. Eds. Susan S. Phillips and Patricia Benner.Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press.

Risse, Guenter B. 1999. Mending Bodies, Saving Souls: A History of Hospitals. New York, Oxford: Oxford UP.

Rose, Nikolas. 2007. The Politics of Life Itself: Biomedicine, Power, and Subjectivity in the Twenty-First Century. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton UP.

Sontag, Susan. 2003. Regarding the Pain of Others. New York: Picador.

Sorrentino, Paolo. 2015. Youth. Indigo Film.

Spackman, Barbara. 1989. Decadent Genealogies: The Rhetoric of Sickness from Baudelaire to D’Annunzio. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

Svankmajer, Jan. 2005. Lunacy (Síleni). Athanor.

Ureczky, Eszter. 2016. Cleanliness as Godliness: Cholera and Victorian Filth in Matthew

Kneale’s Sweet Thames. Travelling Around Cultures: Collected Essays on Literature and Art. Eds. Zsolt Győri Zsolt and Gabriella Moise. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing: 101-117.

—. 2016. Post-bodies in Hungarian Cinema: Forgotten Bodies and Spaces in Ágnes Kocsis’s Pál Adrienn. Cultural Studies Approaches in the Study of Eastern European Cinema Spaces, Bodies, Memories. Ed. Virginás Andrea. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing: 168-191.

Verbinski, Gore. 2016. A Cure for Wellness, 20th Century Fox.

Žižek , Slavoj. 2004. From Politics to Biopolitics … and Back. The South Atlantic Quarterly 103. 2/3.: 501-521.

[1] This work was supported by the project entitled Space-ing Otherness. Cultural Images of Space, Contact Zones in Contemporary Hungarian and Romanian Film and Literature (OTKA NN 112700).

[2] On the Hungarian clinical film, especially the medical gaze, see Király 2015.

[3] Like, for instance, the interconnections of medieval plague and secularization, Victorian cholera and colonization or the 1980s AIDS panic and homophobia (see Ureczky 2016 Cleanliness).

[4] The entry on “Hospitals’” in the Encyclopaedia Britannica is an expressive example of this uncanny model of 19th-century clinical utopia: “Why should we not have – on a carefully selected site well away from the towns, and adequately provided with every requisite demanded from the site of the most perfect modern hospital which the mind of man can conceive – a ‘Hospital City’?” (Armstrong 2002, 130).

[5] In 1881, the New York physician George M. Beard described the psychic impact of acceleration and new technologies of communication as well as transportation with the notion of “neurasthenia” and “American nervousness”, while Philip Coombs Knapp coined the term “Americanitis” for the same condition. Today, cardiac psychologists Diane Ulmer and Leonard Schwartzburd still talk about “hurry sicknesses” (Aho 2009, 34).

[6] The prevalence of ageing in contemporary cinema can be partially explained by Nikolas Rose’s historical view of Western medicine. While in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the politics of health primarily concerned rates of birth and death, diseases and epidemics, the policing of water, sewage, foodstuffs, graveyards and cities; in the first half of the twentieth century a new emphasis was put on the inheritance of a biological constitution, producing growing expectations as to our capacities to control, manage and even engineer human beings (Rose 2007, 3).

[7] The crisis of care can also be approached by Foucauldian notion of the care of the self, for Giorgio Agamben (2015) comments on it as well. He is reading Foucault’s interpretation of the verb chresthai in Plato’s Alcibiades, in which Socrates, in order to identify the “self” of which one must take care, seeks to demonstrate that “the one who uses” (ho chromenos) and “that which one uses” (hoi chretai) are not the same thing. What uses the body and that of which one must take care, Socrates concludes at this point, is the soul (psychč), while chraomai means: I use, I utilize (an instrument, a tool). But equally chraomai may designate my behaviour or my attitude, Plato intends to suggest that taking care of the self means, in reality, to concern oneself with the subject of a series of “uses.” Taking care of oneself will be to take care of the self insofar as it is the “subject of ” a certain number of things: the subject of instrumental action, of relationships with other people, of behaviour and attitudes in general, and the subject also of relationships to oneself. It is insofar as one is this subject who uses, who has certain attitudes, and who has certain relationships, etc., that one must take care of oneself. What is crucial here is the way in which one thinks the relationship between care and use, between care-of-oneself and use-of-oneself (Agamben 2015, 31-34).

[8] See Ureczky 2016 (Post-bodies).

[9] In the early modern era, the hospital was a house of mercy, refuge; while in the Renaissance its central task was to protect and restore working citizens as a house of rehabilitation. By the eighteenth century, state power focused on economics, science and health, and in the 19th century, the hospital especially appears as a house of cure, teaching and research, but also dissection and surgery. In the early twentieth century it was primarily seen as a house of science and high technology, while today’s post-modern hospital may also be failing patients physically just as much as spiritually (Risse 1999, 675-685).