Tales of Necessities and Narrowness

Closed Spaces and Crisis Heterotopias in Everybody in our family (Radu Jude, 2012)

Csilla Patrubány

venianahita@yahoo.com

Abstract: Radu Jude’s complex and versatile filmography seems to follow genre characteristics with a deep inclination towards topics like social and identity crisis, personal relationships questioned, dissonant conversations. The director’s approach and way of presenting the many nuances of post-communist urban existence slightly differs from the realism and immediacy that characterise the New Romanian Cinema. I propose to analyze his film, Everybody in our family (2012) looking at the way he combines melodrama elements with auteur style adapted to the very specific geographical and social aspects of a post-communist Eastern European setting. I will also argue how the chosen cinematographic style accentuates the subject and contributes visually to transform the movie itself in a crisis heterotopy, how closed spaces become figurative of failed connections and domestic crisis. I will also reflect on the deep understanding and empathy of the director, who instead of judging, ridiculing or over-dramatizing his subject and characters, shows a deep connection to the issue and chooses to be a part of this reality, to be present in these closed spaces and dead-end situations, no matter how hopeless and grotesque they become.

Keywords: New Romanian film, melodrama, heterotopia, domestic crisis, realism

Introduction: The “intense realism” of the new Romanian film

With the downfall of the communist regime, something got definitely disconnected in Eastern Europe, something beyond politics, in the private life of individuals too. As if the loosening from the restrictions of the regime did not bring the many polarities closer, but only accentuated the contrast between East and West, old and new, modern and conservative, as well as the differences between generations and cultures.

By the time Radu Jude’s 2012 film was finished, the filmmakers of the Romanian New Weave had become a household notion in international cinematography, harshly shaping the landscape of narrative and representation with their unique themes and cruelly realist style. The fall of the regime, but also the impact it had on different aspects of life, different levels of society become the main point of interest for this young generation of authors, who somehow try to define their ways in the in-betweenness of the historical and cultural changes. Disconnected largely from the generations before, who belonged to the socialist regime, even if it wasn’t a political connection or involvement, somehow they became fatherless, orphaned by the changing political climate and the invasion of the West, in every aspect. What is peculiar about these filmmakers of the Romanian New Wave is that they got close to their stories, talking about the people behind the big machinery of a system, I would say with tremendous humanism and empathy, an understanding for the humans that lived/survived the many shades of a half-century long oppression. They all tell the tales of the humans who did not have a voice or a face for decades, being only the spectators and passive subjects of their life dictated by authority. As Bergan points out, “although several of the new Romanian films can be taken as metaphors of Romanian society, they are, at the same time, almost documentary-like observations of it – disturbing works of intense realism, with an underlining vein of black humor” (Bergan 2008).

Choosing to relate about unseen and unheard stories of the socialist era, under the radar activities that people were forced to do to eschew the dehumanizing decisions that the Party made in their lives, – in a somber and heart-wrenching tone in 4 Months, 3 Weeks, 2 days (4 luni, 3 săptămâni şi 2 zile, Cristian Mungiu, 2006,) or in a humorous, parodistic tale-telling tone, that highlighted somehow the flaws and ridiculed the system, like in Tales from the Golden Age (Povestiri din Epoca de Aur, Cristian Mungiu, 2009), 12:08 East of Bucharest (A fost sau n-a fost, Corneliu Porumboiu, 2006), or presenting generational conflicts, over-protecting, or unacceptable parents, like in Child’s Pose (Poziţia copilului, Călin Peter Netzer, 2013) and The Happiest Girl in the World (Cea mai fericită fată din lume, Radu Jude, 2009) –, characters are generally caught somewhere on borderlines between East-West, capitalism-socialism, dealing with identity crisis, be that gender, age, vocation, belonging, bonding. Their life is full of unanswered questions and displaced, defocused situations. And somehow all conflicts they have to deal with seem to be way above their maturity level, knowledge, means and possibilities.

Not only did they provide a defined thematic parameter but they encouraged a conscious use of style as meaning. The cinematographic style of these movies is as much remarkable as their stories are unprecedented. Opposed to the classic filmography of the past: sticking to hand held cameras, minimalist décor and color-board, plots that develop in one single day, or one single space, the imagery defined an austere, realist, often minimalist style, a prominently black humor and a quasi-documentary style.

Tales of claustrophobia and fury

Thomas Elsaesser in his essay on family melodramas quotes Douglas Sirk saying that in these films the focus in is on “the inner violence, the energy of the characters which is all inside them and can’t break through” (Elsaesser 1987, 43). Periods of intense social and ideological crisis tend to bring out themes of “suffering and victimization”, where “the moral/moralistic pattern which furnishes the primary content … is overlaid not only with a proliferation of ‘realistic’ homely detail, but also ‘parodied’’’ (Elsaesser 45). In a way they manage to present all the characters convincingly as victims. Melodrama is highly defined by its structure, visuality and sound, much more than narrative and action. Sound, as Elsaesser states “acts first of all to give the illusion of depth to the moving image, and by helping to create the third dimension of the spectacle, dialogue becomes a scenic element, along with more directly visual means of the mise en scene.” (Elsaesser 48) The restricted scope for external action is determined by the subject, and is necessary because in melodramas the important changes happen on the inside.

Radu Jude is a director who remained internationally unknown, somehow flying under the radar for years, maybe because of his original and quite out of ordinary approach to subjects and style. I see him having a different view of content than his fellow film makers of the new Romanian cinema: with a deeper understanding and attention to relationships, his characters, their motivations, and a deep empathy towards them. His focus is not so much on the particular aspects of life under communism and the specific characters this era had produced, but on the generation and years after its fall. Dealing with everyday life and the challenges dysfunctional relationships bring, his characters are presented with great humanism and a lot less irony than many movies have got us used to. Also his cinematographic style is a bit further from documentary and closer to a highly conceptual constructed camera use, where the way of telling the story is a reflection of the story itself.

Everybody in Our Family tells the story of Marius, a divorced dental technician living on the perimeters of Bucharest, who plans on taking his little girl, Sofia on a three day vacation to the seaside. When Marius arrives at his ex-wife’s house, he is told that she is ill. He doesn’t believe it and insists that she go with him on the trip and the soon erupting quarrel will slowly but surely reveal the hidden frustrations and critical domestic crisis.

In this accomplished auteur movie Jude implements the fundamental paradigms and characteristics of the classic family melodrama – focus on the inner struggle, great attention on setting and detail, a repressed, tense energy that surfaces – in a very different social and geographical climate, that of the Eastern European harsh reality of big city life and estranged, damaged relationships, struggling on the borderline between old and new, East and West, capitalism and socialism, modern and Balkan. This movie highly lacks action, and the plot builds up in a circular, rotating spiral of non-achievements and the fatal intersection of space and time. Compressed in one single day, or rather in one single morning, the pressure of limited time takes its toll on the characters’ psychology as much as the spatial limitations of the claustrophobic homes do so.

Just like in all well delivering melodramas, orality becomes the main way problems are solved. Or better said: addressed, since solutions don’t really occur as much as the protagonists struggle for them. Regardless of the effort to construct a web of relationships and universe that is familiar, they discover that this world has become “uninhabitable because it is both frighteningly suffocating and intolerably lonely” (Elsaesser 54). Incapable of action, they somehow try constantly to talk their way out of the conflict zone. It is not so much an impossibility for action, nor is it a choice, much rather an incapability. They verbalise the problems and their disagreement, yet fail to take any action that would/could result in a more favorable outcome. They are somehow bound in their sorrow, misfortune, failure, and besides being sad/agitated/angry they just let off steam by verbally fighting. Marius, at the point where he runs out of more or less rational and more or less appropriate arguments, takes the way of action, but in a very wrong and displaced, childish way. A way that is certainly doomed, and will drive him even further from his intention, to what Elsaesser calls in his discussion of classic melodramas an “evidently catastrophic collision of counter-running sentiments” (Elsaesser 60).

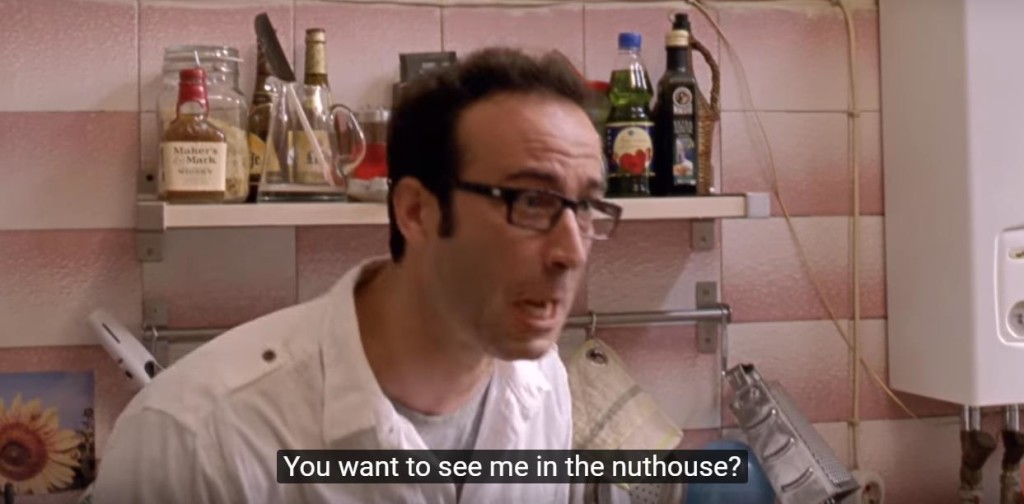

[Fig.1.]. Marius desperately trying to solve the domestic conflicts

In his vast, conceptual work on movies of contemporary Romanian cinema, Hesitant Histories on the Romanian Screen (2017), László Strausz sees this as a failure of the protagonist’s masculinity. I rather see it as a failure of his adulthood. And not because he is infantile, much rather because of the situation he is forced into. Strausz states that many movies build around “leading male characters who experience an identity crisis manifested in their relationships with other family members,” “Under the paternal leadership of the regime, the identity of the male leader of the household is questioned: the parent-state performs and takes over the role of the paterfamilias” – (Strausz 2017, 217) I rather see this as a crisis in their relationship, not neccessarily of their identity and above all not a crisis of his masculinity – whatever that means. His identity remains the same, his possibilities are the ones that diminish.

Of course, his childish and abusive behavior cannot and must not be absolved with this argument, but certainly the circumstances and the people in his complicated relationship web have a great fault in placing him in this rancid, desperate string of events, just as much as he does. It is not an impotence of his masculinity, but just of a certain type of masculinity, the aggressive and dominant paternal way that was a signature for the generations before, and also the way the communist regime exercised its power. And we salute the failure of the paternal, controlling, abusive ways. Marius does not want to assume this role, it is just not the way “modern families” deal with issues. While this movie certainly tries to deal largely with emotional and moral identity, it also registers, and does so with great empathy too, the failure of the protagonist to act in a way that could grant him success and realization in the aspects that matter to him and aspects that validate his entry to a “good life,” one that would allow him to assume the identity of this new and self-assured growing-up/adulthood. The world and the possibilities are closed, the characters fail to have any kind of influence on the environment, emotionally or socially, this “progressive self-immolation” leads to resignation and, as Elsaesser points out about melodrama characters, “they emerge as lesser human beings for having become wise and acquiescent to the ways of the world.” (Elsaesser 55) Marius, the protagonist of the film and an orthodontist technician, wakes up in a suffocating, crowded studio apartment in the peripheries of Bucharest. Although it’s only early morning, it seems impossible to breathe, the air is already steaming hot and noisy, the agitation of the big city flows in through the open windows like the heat weave. As he twirls around the tiny space, trying to pack and get on the road, we only feel uncomfortable by his closeness and fast movement, but as the plot slowly develops we realise that it is not only his living space that is unbearably tight and frustrating, but his life itself is a well-managed crisis, that is restrained from exploding with great effort.

In the first round, the situation is just unpleasant: summer, panel, heat, and hesitations from early morning. But for now there is no tragedy, no life-death matter. However, the private drama, the family crisis is becoming acute to the extent that it exasperates the walls of the panels and the limits of human tolerance. The spaces in which he moves, in the same way as his life situations, are hopeless, overwhelming, and close in like jail bars on all outbursts of intent to escape. No rooms with a view are available in this film.

The mess is only partially intimate, most of it is chaos. There is no order and transparency, the characters move around the objects of their space as well as the remains of their past. Like narratives of pressure condensed in the objects of everyday life, all are meant to build up tension and deliver one more revealing aspect of the character’s well contoured profile. Every step must avoid something; it must be a strategic maneuver, a movement that is not driven by intent and élan, but by necessity and tactics. It sets of, gets lost, reroutes. Two steps ahead, one step back. One step ahead, one on spot.

[Fig.2.]. Chaos and mess, as the visual elements for building up domestic crisis

Yet, in this first scene the situation seems under control: the alarm clock works, the luggage will be ready, all packed for the trip. Although we are choppy and stalled in a claustrophobic studio, the long settings and the motionlessness of the fixed camera counterbalance the closeness of the space and Marius’s agitation in it. There is no crisis yet, there is still hope and a journey follows. Check: clothes, books, child seat for bicycles, a giant toy octopus with all eight arms, backpack, some plaster dental prints. Marius is not necessarily an anti-hero in the overture, although he is certainly vulnerable in the Bucharest traffic, being on a bike, accompanied by a giant, stuffed octopus. But he is still in the saddle. The film is moving forward slowly, with the calm and cool of a resonator who sees everything, is present everywhere but never interferes. The clashes and ruptures of the laid out fabric of the story are still well tucked under the sunny scenery. Like a bon-vivant character in a nouvelle vague film set in Paris, Marius rides his bike oblivious to the chaos that the events turn into. None of the hysteria bubbles to the surface just yet, we are below boiling point.

On the inside, looking out

As we move forward from place to place, the space is getting narrower, tense, warmer and more and more conflict follows, in a domino effect way. The mobility of the protagonist – which has a key meaning, as it allows him distancing in both space and time from the role and the situation he is forced into – becomes increasingly restricted, senseless and bound nowhere. The film uses an interesting contrast game between the use of internal and external spaces, in order to build up the structure of tension. The inner spaces are small, seemingly closed regardless of the open, ventilated windows, choked with frustration: full of objects of life that fill every shelf, tossed around every corner, taking up every space. The outside, the public space is one of a crowded, agitated streets of a big city, but very clearly not a western one, but a cramped up and noisy Balkan atmosphere.

Although at a cost of a few rounds of near-stroke stand-offs, Marius manages to leave his parents’ flat and even gets a tool to make it easier to get the job done: he borrows his father’s car and escapes followed by the avalanche of curses and grievances, but ultimately gets rid of the situation, the flood of reproach of his father and the apartment blocks hovering around him.

Although the crisis situation between generations is a given, as in many films of the New Romanian Cinema, here it is not of central importance. Yes, the relationship and communication towards the elderly generation, accustomed to the communist regime and socialist ways, is permanently damaged, but here it is merely of secondary importance, it is just a step in the direction of the big showdown. Stela Popescu and Alexandru Arșinel, who play the protagonist’s parents and are well known actors and TV stars in the country, give a stellar performance, making these pajama and slipper clad, make-up free characters memorable and very revealing. Although Marius is almost thrown down the stairs by the mahala[1]-style family argument, he goes on undisturbed, because this team is still on his side, cheering on him.

But as soon as the story approaches to his ex-wife’s home, things seems to take an irremediable turn towards chaos, which eradicates intent with the technique of tiny steps and small cuts. A vivisection that clears up all possible escape routes and invalidates all illusions of Marius regarding himself and that he was trying so hard to keep up: the peaceful human, decent man, the good father, the good citizen that he was so attached to.

In this movie, the so quintessential motifs of Eastern European movies, movement and crisis situations are presented and built up with the sensitivity of a master-psychologist: there is no spectacular action or world-changing game, but the crisis is unstoppably escalating so inevitably that Éris herself could not have done it better. As Elsaesser states,

the discrepancy of seeming and being, of intention and result, registers as a perplexing frustration, and an ever-increasing gap opens between the emotions and the reality they seek to reach. What strikes one as the true pathos is the very mediocrity of the human beings involved, putting such high demands upon themselves trying to live up to an exalted vision of man, but instead living out the impossible contradictions that have turned the American dream into its proverbial nightmare. It makes the best American melodramas of the 50s not only critical social documents but genuine tragedies, despite, or rather because of the ‘happy ending': they record some of the agonies that have accompanied the demise of the ‘affirmative culture’. (Elsaesser 67-68)

And the protagonist, despite all his efforts to avoid sinking, gets snatched by the whirling of the vortex and is nullified in his freedom and choices. Locked up, literally, in a prison with no walls, from where he can only shout and curse his way out, his angry rant being the only tools of making himself visible, existent.

Using frames as narrative defocalisation

It seems as if the downfall of walls, confined spaces and physical delimitations of the communist regime was in vain, the catharsis failed against all efforts to make it happen. Confinement can be anywhere: constraint and strict timetables, limitations of schedule, small spaces, and bad relationships will give the human soul unnoticed damaging and hopeless subversion that is more harmful, as it is an invisible, silent erosion, than the political system. As Elsaesser argues, “Melodrama is iconographically fixed by the claustrophobic atmosphere of the bourgeois home and/or the small town setting, its emotional pattern is that of panic and latent hysteria, reinforced stylistically by a complex handling of space in interiors … to the point where the world seems totally predetermined and pervaded by ‘meaning’ and interpretable signs.’’ (Elsaesser 62)

Access to spaces already is a problem, and from this point on, doors will have an important role as gateways of possibilities. There are plenty of doors in this house, like in a nightmare from a Hitchcock movie, like the castle of Bluebeard, and as it happens in this archetypal story, they are all locked and they all hide something. A new space for the crisis, a new shade of conflict, the direction being: in and down. One has to ring, knock, identify oneself, repeated several times. Getting in and out is not a simple step that one always does in everyday life as an unnoticed automation. But once a door is locked it becomes a marked event, a crisis, a polarization between inside and out. But there is trouble here, and the cumbersome, difficult advancement also indicates that here the order is broken at all levels. Calmness and smiles are neither peace nor consensus. They are a fragile glaze, a fable, a compulsive game that breaks down human relationships and the basic values of civic existence: respect, family, love, harmony and well-being. As Foucault states, “the heterotopic site is not freely accessible like a public place. Either the entry is compulsory…or to get in one must have certain permissions and make certain gestures always presuppose a system of opening and closing that both isolates them and makes them penetrable.” (Foucault 1986, 26)

Opening each door is a situation to be solved, a task, a challenge and a crisis situation at the final stage. Marius enters his ex-wife’s apartment, which, though more spacious than the previous spaces and, in principle, in the past, was his own and well-known terrain, now becomes a crisis heterotopy. There is no entry for our hero, not for financial reasons, but because the contract guaranteeing entry was dissolved: he is divorced, and kicked out from his marriage, his home, his life, his fatherhood, the whole order and is declared persona non grata, against his will.

The home he once belonged to becomes a morphed space of vast failure specter: instead of bringing the place where safety, familiarity, reassurance and happiness dwell, it becomes the exact opposite of all these conditions of a decent life. Marius, once he lost access to call this place a home, loses all the emotional connections to it too, and we can watch the marital home being turned into nut-house, the locale of crisis of the family. A crisis heterotopy is a delimited space that exists in the real/non-critic life, but is enclosed not only in space but also time and it is meant to house individuals who are in a situation of crisis. Modern day heterotopias are also conditioned spaces, with limited access, and one must have entry granted by some form of token. It is very important that they are never owned by their inhabitants, their stay almost always being closely connected to time and time limitations. Prisons, hospitals, police offices, asylums are evident examples to these “other spaces” that are not able to produce good experiences or memories worth keeping, they manifest some form of restraint, are closed and therefore tense with pressure. Exactly what his former home has become to our protagonist. Marius does not want to be here either: he just wants to take his daughter with him, for two days of vacation by the sea. But all his efforts to be well groomed and accepted, to be granted entry are in vain: although he comes with a smile, a white shirt and gifts, as the etiquette demands him to do, acting exemplarily, no is the answer to all his questions and movements. There are not even this many no-s in the whole world and in line with the outing of all his plans he becomes more and more lost and his reactions are those of necessity and escape of a cornered animal.

The house itself is an uncanny labyrinth system full of traps. And the life situation as well. Marius does not want anything except to bring out the most from the humiliating, even worse situation than Sunday’s fatherhood: to not be forgotten, thrown out of his child’s life and love. But life follows, like an attentive and diligent saboteur, and overwrites his intentions. On this obstacle course he has to finish, the problems to overcome and be solved are growing, always with a circle narrower, one degree warmer, with a shade more hopeless. Marius is greeted with the news that his ex-wife is not at home, his daughter, Sophie is ill, she cannot go to him, she sleeps, is not visible, his ex-wife does not answer the phone, his ex-mother-in-law’s kindness is useless, she is rather a kind of moving toy than an adult (portrayed by Tamara Buciuceanu-Botez’s wonderful acting).

The many doors in the house and in the film constantly open and close, but mostly close. For a moment Marius seems to be able to get out when he knocks out his ex-wife’s current partner with the door, but his small daughter, scared of the circus, runs back inside. And with Otilia, his ex-wife coming home, the intense emotions and anger held civilised so far with great effort, wash over the space and storyline as an inevitable tsunami wave. The characters engage in a ludicrous word fight, twitch and rotating hysteria, which puts to shame a New Year’s Eve cabaret in ecstatic and the very uncomfortable couple of Liz Taylor-Richard Burton from Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf (1966) in hurting each other in an elaborate way.

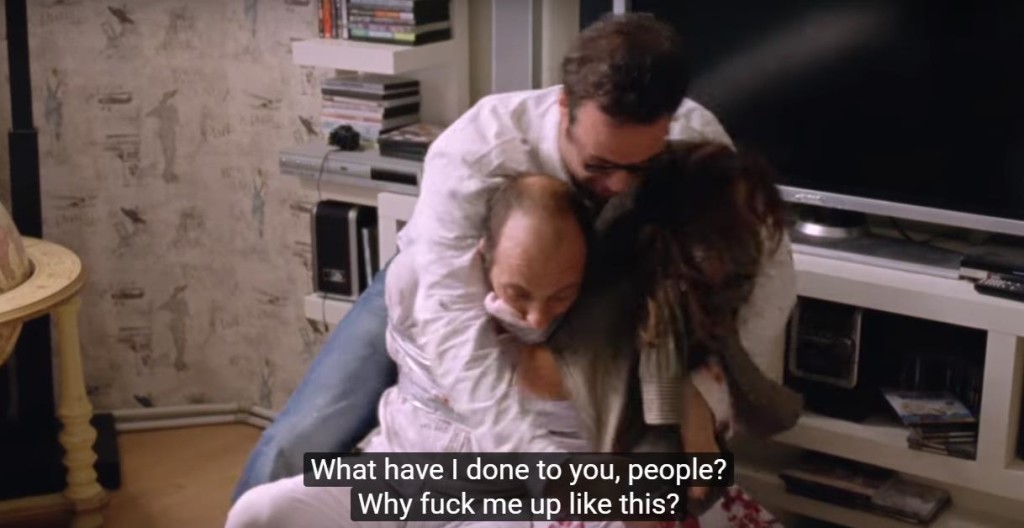

In line with the main character of the melodrama, that somehow manipulates tension and displacement to emphasise pathos and irony, the movie intentionally leaves the grotesque and drama next to each other. With the constant banging and ringing of the police, Marius cannot win a battle: to take the child, to exercise his rights or to go away with intact self-esteem. In fact, he can’t leave in any way. He ties up Aurel (Gabriel Spahiu) and Otilia (Mihaela Sîrbu) not because they pose a threat, but to create a somewhat identical vulnerability, to level up the uncomfortable, speechless state in which he was pushed and bound in.

[Fig.3.]. Lack of consensus and forms of restraint as effects of alienation

But like any attempt to act tough, this one also turns out somehow absurdly funny, as there is no way out, they are upstairs, the police is in the doorway, the report has been made, and although the two opponents are immobilised, he does not win this battle.

Though the film remains in the frames and styles of realistic depiction, it still has important added content, and apparently conceptualises and formalises certain objects, figures, and replicas.

The attention given to all the details and elements of décor, costumes, location arrangement and placing of the objects seems to pay well off, because they all prove to help build the structure of this intense family melodrama as well as compress tension and character depiction amazingly well. The setting is built with millions of objects, pictures, kitsch, and also costumes are chosen in a way that would allow the actors them to create memorable characters even in very small roles. As Elsaesser states,

the banality of the objects combined with the repressed anxieties and emotions force a contrast that makes the scene almost epitomise the relation of decor to character in melodrama: the more the setting fills with objects to which the plot gives symbolic significance, the more the characters are enclosed in seemingly ineluctable situations. Pressure is generated by things crowding in on them and life becomes increasingly complicated because cluttered with obstacles and objects that invade their personalities, take them over, stand for them, become more real than the human relations or emotions they were intended to symbolize. (Elsaesser 62)

As in the 17th century Dutch painters’ pictures, interlocking room interiors and intimate details are opening in front of us, and we become part of the plot, as keyhole peepers and eavesdroppers. The many openings lead the viewer’s gaze through a series of thresholds and spaces and also “stage a plunge through…an entrance to a deep interior.” (Pethő 2016, 45) The film often emphasises the act of looking in and out, Marius himself is constantly looking out on the windows, longing for the outside, panning, spying, searching.

[Fig.4.]. Forms of delimited spaces to emphasise the lack of connection

Windows and doors being the markers of borderline, the things that separate two different spaces, inside and outside, private and public, the people placed next to them are themselves in some way and aspect of their identity or life in a “liminal” situation” (Pethő 46). Still, the many small details and the interconnected spaces do not shape a space and sense of intimacy and family nest, but one of chaos and dizziness, because there is the lack of cohesive power, the love that makes the house a home. The rooms are all fragmented, space is divided by all kinds of frames, the image is not whole, there are missing pieces, like in a jigsaw puzzle. The play with “framing and de-framing, upon the visible and the invisible” allows to peep through windows, but the inner walls are “impenetrable to the gaze” (Pethő 50) and the objects of everyday life function as limitations, “occluding the view.”

The separation of spaces, of what is in the frame and off-frame is emphasised with the characters’ interaction with the inhabitants of the space not visible on frame/to the viewer. They interact, talk trough doors, interphones, phones, walls, doors, they constantly relate to a presence that is not physically present but constitutes a source of conflict. It is a good way to underline the estranged relationships of the protagonist, of domestic alienation. It is never a face to face discussion, people even if they eventually get in the same place, they instantly ignite an argument that leaves one of them offended and abandoned. Their familial interactions are constantly interrupted by some external factor: the police, the funeral, the car claxons, the TV, the phone. Connection between people fails to come into being.

Space and subject together determine the position of the camera: the camera and the viewer become a part of the action. We cannot escape the drama, just like Marius, we cannot go outside, it is locked in the crisis and the viewer also. It is not only the signature imagery of the contemporary Romanian film but plays an important part in building up the tension. At the same time, it is a masterpiece of the cinematographer: we follow the running of the actors in this cave system with a handheld camera, and thanks to the continuous movement and the long takes, we as viewers have no options either, no escape, no comfortable distance, we have to stay in the center of the fire with the characters.

The position of the viewer is that of an observer who shares the domestic space with the feuding family members. The medium shots place us in the close proximity of the characters, and the bewildered pans and tilts of the handheld frame establish the viewer’s observation of the heated conversations by curiously exploring gestures and reactions, as if inquiring about the outcome of the events. The heat is almost suffocating the viewer and we stumble across spaces trying to figure out which is the right door that could finally lead out from the chaotic circus, not constantly deeper and deeper down on the spiral stairs, to an emotional rock bottom with a basement. The film’s important feature is that it creates a point of view that does not get involved, stays outside, but still affects us deeply. It is out of the action, it does not interfere, but follows its characters wherever the story takes them, to the deepest level, in every space and in every debate. And perhaps this is the most empathic behavior that man can apply in a crisis situation: non-flogging, no-judgment, presence that also ensures the warring without words: you are not alone. Radu Jude is the master of this selfless, deeply human and discreet empathy: he is not cheering but neither condemns. He does not offer a solution to his protagonist, but neither does he leave the site of his characters in the chaos of border zones.

The film has no final solution. The ending is just as grotesque, somewhere near the boundaries of comedy and tragedy as the rest of it: Marius locks up everyone in a space and then escapes, that is, he jumps, scared to death, in a hideous inner courtyard filled with debris, without exit, surrounded by firewalls, sky high stone walls defining the escape route. When he finally makes it to the streets, bruised, bloody and tormented, he is bandaged up in a pharmacy, he takes off his white shirt, the white banner of peace that he took for the sake of formality at the beginning of the day, throws it into the trashcan, replaces his magic-stick “electronical Zigarette” he asks for a “real” cig from the pharmacy security guard who cries out with the proper irony of the film’s biblical closing phrase: “Lazarus, get up and walk!”, and this irony is exactly the element needed, “to underscore the main action and at the same time ‘ease’ the melodramatic impact by providing a parallelism” (Elsaesser 45).

Retrieving movement and mobility is, however, an optimistic closure, a bright solution to the problem, which has been dancing on the borderline through the entire movie and puts on a comic finale. Although senseless, although grotesque, disintegrated and out of sight, Marius, just like any person in crisis, does not become ridiculous, but in some ways will be a marker of survival and faith in change. And this is life as compared to frozen immobility.

References

Elsaesser, Thomas. 1987. Tales of Sound and Fury. Observations on the Family Melodrama. In

Home Is Where the Heart Is, ed. Christine Gledhill, 43−70. London: BFI Publishing.

Foucault, Michel. 1986. Of Other Places. Diacritics, Spring 1986, 22−27.

Király, Hajnal. 2015. Leave to live? Placeless people in contemporary Hungarian and Romanian

films of return, Studies in Eastern European Cinema, 6:2, 169−183.

Pethő, Ágnes. 2015. Between Absorption, Abstraction and Exhibition: Inflections of the

Cinematic Tableau in the Films of Corneliu Porumboiu, Roy Andersson and Joanna Hogg, Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, Film and Media Studies, 11, 39−76.

Strausz, László. 2017. Hesitant Histories on the Romanian Screen. Palgrave Macmillan.

[1] Mahala is a Balkan word for neighborhood or quarter on the peripheries of urban settlements.