Retreat into the Spaces of Consciousness (download pdf)(download pdf)

Miklós Sághy

Abstract: A distinct tendency can be detected in contemporary Hungarian film, namely the presentation of protagonists who leave public spaces and retreat to the “safe haven” provided by the private sphere. The term retreat can be applied to these kinds of movies which depict primarily the process of retreat as a real spatial movement, since the protagonists literary retreat from society, from public communal spaces, from the city, from the world of specific human interactions. As far as I can see, contemporary Hungarian films display yet another form of retreat, which can be interpreted not as a real but as a mental movement, as a retreat into mental spaces. From that perspective I analyze three Hungarian films: Liza, the Fox Fairy (2015), The Investigator (2008) and Adrienn Pál (2010). In my interpretation I show that the (male and female) protagonists live withdrawn into their body and mind. This state appears as a substantial closing down, and as a retreat to inner, mental spaces. Eventually, all three main characters will be able to step out of their mental and psychological isolation into the larger spaces of social (inter)action. However, the precondition of these stepping outs is facing their traumatic past.

Keywords: retreat, post-communism, post-socialism, contemporary Hungarian film, consciousness-film, traumatic past, Taxidermia, Delta, Liza, the Fox Fairy

Retreat into the private sphere

It has been observed and described several times that films directed by Hungarian directors starting their careers in the 2000s display a tendency in which films do not focus on specific social problems, they cannot be related directly to contemporary Hungarian reality, they do not put on themselves the presentation of topical social debates.[1] (Gelencsér 2014, 323; Gelencsér 2017, 238–242; Király 2015, 186; Király 2016, 71.) Their heroes do not fight for a community, do not represent a social group, but are a lot more likely to be standing in front of us as lonely, marginalised human beings struggling with personal problems. The disappearance of a specific reference obviously brought about a change towards the more abstract both in terms of the form of expression and that of the world depicted. Interestingly enough, Hungarian film (and literature) in the 1980s displayed a similar artistic predilection for more abstract expressions, and, similarly to contemporary films, it was also accompanied by a distinct turn away from social reality. As Ernő Kulcsár Szabó wrote about the 1980s: the difficulties of narration (e.g. the masterful creation of the text itself, reflection, wordplays) had become more important than the actual topic of the literary text. (Kulcsár Szabó 1993, 144–160) This tendency could be very easily explained in the 80s, when individuals had no possibility to exert any influence on public affairs during state socialism, especially if they held differing views from the principles of Communist ideology. So, as influencing public affairs and being actively involved in the political arena had become partially impossible and partially dangerous in Hungary, finding refuge in the private space after having retreated from the public sphere became a compelling strategy. As Jacqui True argues when writing mainly about the Czechoslovak state-socialism during the 1970s and 1980s because “possibilities of exercising influence in an outward direction – in the public sphere – no longer existed, people diverted more of their energy in the direction of the least resistance, that is, into the private sphere”. (True 2003, 34)

I argue that the cinematographic (and literary) alienation from social reality and social problems in the 1980s can be compared to the abovementioned tendency in film in the 2000s. The euphoria after the change of the political regime was soon followed by a period of disappointment and the recognition that the transformation of the mentality of people which was fashioned under a totalitarian rule, was a difficult and lengthy process. No wonder that the change of the regime in Hungary led to “an inhuman, unjust, unfair, inefficient, anti-egalitarian, fraudulent, and hypocritical system that is in no way at all superior to its predecessor, which was awful enough”. (Szeman and Tamás 2009 – quoted by Kalmár 2017, 11) Even then, the majority of people couldn’t feel as if they had a real say in public affairs, politics, or that they could have equal access to public goods in terms of their merits. In short, citizens of post-communist states had to face the fact that the change of regime (the accession to the EU) did not bring about fundamental social changes and that dealing with public affairs and running administrative errands still mimicked state-socialist patterns. In the light of this, it seems that retreating, turning away, or backing away from public affairs in the 2000s, after the 1980s, was a current strategy in Hungary and in post-communist states in general.

György Kalmár in his essay Rites of Retreat in Contemporary Hungarian Cinema analyzed thoroughly and persuasively the modes in which the different (social) strategies of turning away and retreating are present in contemporary Hungarian films. According to him, similar cinematic phenomena from before the change of regime are straightforward predecessors of these: “I would argue that post-communist cinematic returns and retreats can be interpreted as a reinvention of an old, well-used pattern of behaviour on the part of Eastern-European men.” (Kalmár 2017, 23) In the 2000s, Kalmár argues, Hungarian society was characterised by a disillusionment and demoralization similar to that of the decade before the change of regime. The impossibility of fair and sensible public activity inspires protagonists in films to leave public spaces and to retreat to the safe haven provided by the private sphere. Or, as Kalmár puts it “many male protagonists of post-communist Hungarian cinema tend to return from their westbound journeys, often so as to withdraw from the open, public (traditionally masculine), usually urban spaces of self-liberation, from the possibilities of establishing more authentic, publicly accepted identities, thus creating unusual spatial patterns and peculiar masculinities.” (Kalmár 2017, 10) Kalmár uses the term retreat film to designate movies which depict such movements and retreats and describes the path taken by protagonists as follows: “Their spatial trajectories may typically lead from Western cultural centres to Eastern homelands, from cities to the countryside, from the public sphere to the private, sometimes symbolically from the future to the past, and often from the realm of desire to that of Thanatos. The men of these films tend to struggle to find places of their own on the margins of society, away from public spaces: what they seem to have in mind is a place to hide, somewhere to retreat.” (Kalmár 2017, 11)

Kalmár, therefore, 1) primarily describes the process of retreat as a real spatial movement, which, at the same time, 2) is also used to determine the creation of a new masculine (counter) identity. Or, in short, spatial movement, as described by him, embodies the possibility of the creation of a new male identity.

György Pálfi’s Taxidermia (2006) and Kornél Mundruczó’s Delta (2008) figure in Kalmár’s analysis, among others. The protagonist of the latter, Mihail returns to his homeland, the estuary of the Danube, after having spent a longer period of time working in Western Europe and “he would simply like to build a log-house on the river in the astonishingly beautiful and untamed wetlands of the Danube Delta (where his father used to have a fishing hut), so as to hide away from the world.” (Kalmár 2017, 16) [Fig.1.] The last progeny of the family whose story is depicted in Taxidermia is called Lajoska, who works as a taxidermist. He retreats into the sterile world of his own workshop, or, in other words, he exiles himself to the midst of prepared, stuffed animals even though he does not disclose the external reason for his exile. [Fig.2.] Kalmár supposes there are nebulous psychological reasons behind his exile, and, partially, some family history: “there is no outside power forcing him into exile. No visible »outside« factor destines Lajoska to live his life surrounded by dead things in his cold, literally lifeless labyrinthian den. The film suggests that his miserable existence is only due to opaque psychological reasons, or the weight of the family history on his shoulders.” (Kalmár 2017, 15)

Kalmár’s excellent analyses focus primarily on real spatial movements, as the protagonists in the films he chose for analysis literally retreated from society, from public communal spaces, i.e. from the city, the village, from the world of specific human interactions.

As far as I can see, contemporary Hungarian films display yet another form of retreating, which can be interpreted not as a real but as a mental movement, as retreating into mental spaces. Obviously, Kalmár always connects movements in real spaces with the process of identity formation, so in that respect, he also speaks about metaphorical, symbolic spaces; however, in the cinematographic examples he cites, the spatial/physical markers of retreat can also be observed and identified (which, accidentally, are/can be experienced by the other characters in the movies, so they are part of the (common) reality). In what follows, I will focus on the representation of this mental retreat in some Hungarian films.

Retreating into the mental sphere

But what does exactly this mental, non-real, non-spatial retreat mean? To illustrate, let me introduce Károly Mészáros Újj’s movie, Liza, the Fox Fairy (Liza, a rókatündér) released in 2015 in Hungary.

The protagonist of the film is Liza who leads a lonely and withdrawn life. The film, however, does not provide a logical explanation for her loneliness (it rather uses a fairytale-like one: Liza was cursed just like a Japanese lady called the fox fairy, who accidentally killed every man who became close to her). In the film Liza’s loneliness, however, is not depicted as a depressive, desolate, bleak state, but as a colorful, musical, fabulous world, populated by Liza’s dreams and fantasies. The most important character there is Tony Tani, a long-dead Japanese pop singer. [Fig.3.] Liza escapes from a scary and cryptic world into one created by her own imagination, a beautiful, romantic one; in short, her retreat from her (crippling) loneliness is her imagination. In the case of Liza, the Fox Fairy a mental, subconscious space serves as shelter from loneliness, from where only another lonely hero, blessed with similar (musical) fancies, Zoltán, can save her. According to Hajnal Király, the film offers a “playful alternative to the narratives of disenchantment and escapism pervasive in contemporary Hungarian cinema.” (Király 2017) The plot lines of retreat and escapism appear in this movie, but Liza, the protagonist escapes into mental spaces instead of real external spaces. I would like to emphasise again that Liza is capable of stepping out, eventually, of the state of retreat and loneliness with the help of Zoltán.

In the following analyses I will focus on two films which, on the one hand, represent the way from isolation and retreat towards some kind of a way out (just like in Liza, the Fox Fairy), and, on the other hand, in which the state of isolation and retreat figures as a mental state; however, the mental states of the protagonists do have spatial poetical aspects. The two cinematographic examples are Attila Gigor’s The Investigator (A nyomozó, 2008) and Ágnes Kocsis’ Adrienn Pál (Pál Adrienn, 2010).

Retreat from the world of the living (The Investigator)

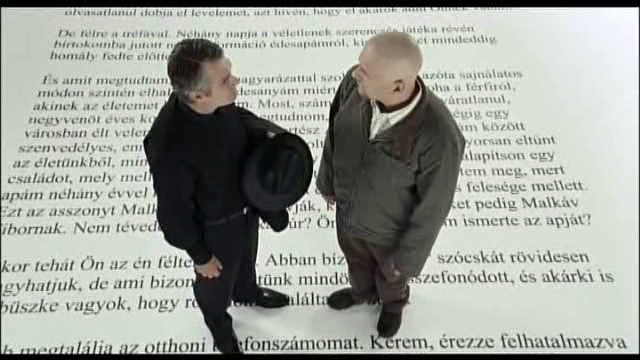

Tibor Malkáv, the medical examiner protagonist in The Investigator is depicted, even at the very beginning of the story, in complete isolation. He has closed most communication channels towards the outside world: he rudely turns down his colleague’s regular invitation to parties, and his verbal utterances are limited to a bare minimum. The character shuts himself down and the most spectacular way of showing this is his blank, expressionless face, as no joy, no sorrow, and no emotion can be detected on Tibor’s face. [Fig.4.] The lack of communicative needs and the extent of his isolation is clearly shown by his limited language usage. In several scenes in the film it turns out that he is incapable of reading between the lines or understanding indirect speech acts, as if he hadn’t studied his mother tongue among people but from a book (alone).

The fact that he works as a pathologist, amongst the dead, clearly marks his retreat from the world of the living. He spends his days among dead bodies, in the border realm between life and death.[2] (The vacant, unflappable face of the protagonist resembles considerably the lifeless face of the dead.) Tibor is (still) alive but he has withdrawn himself completely to the confines of his body without sending hardly any communication signals. Even though there are tale-like, fantastic scenes in the film which allow a peephole into Tibor’s inner world, similarly to Liza, the Fox Fairy, these “products” of his imagination are invisible to the other characters in the movie (because they cannot see inside the investigator’s head), so for them, Tibor’s dull, expressionless face is the “real” experience. [Fig.5.]

The film does not inform its audience about the reason for Tibor, the investigator’s isolation. There is a short allusion though to the notion that his past and his upbringing is to blame for how he is now: once when he touches his old, unconscious, sickly mother, she starts to bawl desperately as if human contact caused her physical pain, an allusion to the idea that in her family the expression and display of emotions was never allowed.

There are two sources of inspiration which force Tibor to leave his mental and real seclusion. On the one hand, he is coerced into committing a murder to save her mother (to raise money for the expensive medical treatments). On the other hand, he realises that the murder was an ambush so he starts his own investigation to uncover who set the trap for him. During the investigation it turns out that his victim is his half-brother, Ferenc, a son his father had in a previous marriage, and Ágnes, who commissioned him for the task also turns out to be a half-sibling who wants the considerable inheritance for herself. As the plot lines around and details of the murder uncover unfamiliar relationships and ties for Tibor, the process of the investigation serves as the mapping and understanding of his own past. The fundamental question of Tibor’s investigation, therefore, does not focus exclusively on who set the trap for him but equally importantly also on the family secrets buried deeply by his mother. Facing his personal past and the transgenerational silences allows Tibor, the medical examiner to step out of his isolation and to move over the borders of his claustrophobic world.

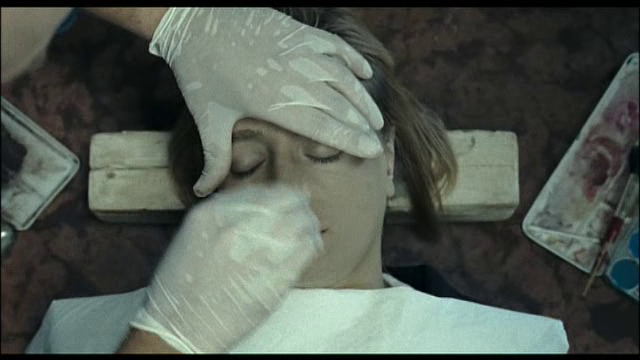

It is important to mention that a female character provides great help for him during the course of the investigation of his past, and simultaneously assists him when stepping out of his isolation. She is a waitress who maintains throughout the movie her belief that Tibor’s expressionless face, his “death mask” hides a living and feeling human being. There is a lovely scene at the end of the film when the investigator is making up the waitress’ face. After all, he does have sufficient experience with applying make-up on dead bodies when preparing them for funerals, but this time, the face being made up springs to life: the eyes open and stare at him. [Fig.6–7.] This first frightens Tibor, then, after a couple of seconds of hesitation, he continues his work, accepting, in this symbolic scene, the fact that from now on he will be working with the living, not only with the dead.

Retreat into an obese body (Adrienn Pál)

The protagonist of the film titled Adrienn Pál, Piroska is in a way the female counterpart of Tibor, the investigator. Her face shows no emotions, and she leads a lonely life exiled into an obese body. [Fig.8.] She has a fiancé but she is not attached too much to him: she listens to his monologues with a blank expression on her face. So, not surprisingly, one day he packs his suitcases, leaves a short telephone message and leaves Piroska’s life for good. Piroska resembles the investigator in terms of her job too: she also spends her (work)days among the dead and the half-dead, as she works in a hospital, in a ward where the terminally ill patients are treated. These patients are unconscious bodies, mainly “sentenced to death” and her job includes taking care of them, washing them, and eventually transporting them to the morgue.

In the movie we can see Piroska several times (both at her workplace and at home) withdrawn into the bathroom which she doesn’t use but where she hides, retreats from the others. In one scene she is at home, sitting on the toilet, and she is going through a suitcase of photographs and mementos of the past. We get to know that her fiancé doesn’t even know this suitcase exists because he has an angry outburst when its existence comes to light. In this sense, the toilet is the real space of complete retreat and retirement, her “own space”.

The film does not explain what compels Piroska to such a mental withdrawal and isolation, but as no obvious external reasons seem to play a role in this, psychological problems are more likely. This suspicion is reinforced by Piroska’s eating disorders: we see her several times gorging and vomiting.

Another commonality between the stories of Piroska and the investigator is that they are both driven to step out of their own mental isolation by an unexpected, personal event in connection with their (traumatic) past: there is a new terminal elderly patient named Adrienn Pál in the ward where Piroska works, who shares the name of Piroska’s best friend in primary school. This coincidence pushes Piroska to look for her former friend but her efforts are fruitless. Piroska visits several former classmates and teachers in vain as she cannot find any clues to Adrienn Pál’s whereabouts. Moreover, during the course of this “investigation” into the past Piroska constantly gets confused with Adrienn, as if Adrienn and Piroska were one person. It is no accident that Piroska speaks about the “mysterious” Adrienn as her twin sister and the other part of her soul. Therefore, the investigation into Adrienn Pál can be interpreted as Piroska’s quest for her childhood self in order to understand how she ended up as an adult in a state of physical and mental isolation (and quasi-clinical death).

There are no real results of the investigation of the past (there are no traces of Adrienn), but walking in the spaces of her past and facing her past resuscitates Piroska. The final scene of the film suggests this. First we see as Piroska and her young colleague are staring at the EKG monitors in the observation room, without saying one word. [Fig.9.] We hear several heart monitors beeping accompanying the EKG graphs on the monitors. The cacophony of heart beats is gradually replaced by the sound of a single pulsating heart as the camera closes up on Piroska’s face. The linking of the lonely heartbeat with the close up can mean that we hear the sound of Piroska’s “reviving” heart, or the story comes to a close with her “awakening” from her “coma” and leaving her prison of loneliness. [Fig.10–11.]

Conclusion

In the beginning of the films The Investigator and Adrienn Pál, both the male and the female protagonists live withdrawn into their own body and mind. This state can be characterised towards the exterior as a substantial closing down, and as retreating towards the inner, mental spaces. Both films imply that the isolation is the result of some past (not necessarily conscious) trauma or injury because facing the past, investigating the past makes the protagonists step out of their mental retreats eventually, or, at least start on the path. In other words, they leave the dead of the morgue and the half-dead of the terminal ward for the world of the living.

If György Kalmár describes the plot line of the retreat films as withdrawing into narrower and more personal spaces, I argue that the protagonists of The Investigator and Adrienn Pál walk an inverse path: they are capable of stepping out of their mental and psychological isolation into the larger spaces of (social) action, eventually.

References

Gelencsér, Gábor. 2014. Az eredendő máshol. Magyar filmes szólamok [The original

elsewhere. Trends in Hungarian film]. Budapest: Gondolat Kiadó.

Gelencsér, Gábor. 2017. Magyar film 1.0 [Hungarian film 1.0]. Budapest: Holnap Kiadó.

Kalmár, György. 2013. Body memories, body cinema: the politics of multi-sensual counter-

memory in György Pálfi’s Hukkle. In Jump Cut No. 55, Fall 2013.

http://ejumpcut.org/archive/jc55.2013/kalmarHukkle/index.html. Last accessed 16. 06.

2017.

Kalmár, György. 2017. Rites of Retreat in Contemporary Hungarian Cinema. In

Contact Zones 2017/1. 10–25.

Király, Hajnal. 2015. The Alienated Body. Smell. Touch and Oculocentrism in

Contemporary Hungarian Cinema. In The Cinema of Sensations, ed.Ágnes

Pethő. 185–208.Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Király, Hajnal. 2016. Playing Dead: Pictorial Figurations of Melancholia in Contemporary

Hungarian Cinema. In Cinematic Bodies of Eastern Europe and Russia. Between Pain

and Pleasure, eds. Ewa Mazierska, Matilda Mroz and Elzbieta Ostrowska, 67–88.

Edinburg: Edinburgh University Press.

Király, Hajnal. 2017. Sonorous Envelopes: Pop Music, Nostalgia and Melancholia in

Dollybirds (1996) and Liza, the Fox Fairy (2015). (Manuscript)

Kulcsár Szabó, Ernő. 1993. A Magyar irodalom története 1945–1991 [History of Hungarian

Literature 1945–1991]. Budapest: Argumentum Kiadó.

Strausz, László. 2011. Archeology of Flesh: History and Body Memory in György Pálfi’s

Taxidermia. In Jump Cut No. 53, Summer 2011.

https://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/jc53.2011/strauszTaxidermia/ Last accessed 16. 06.

2017.

Szeman, Imre. 2009.The Left and Marxism in Eastern Europe. An Interview with Gáspár

Tamás Miklós. In Mediations, Vol. 24. No. 2.

http://www.mediationsjournal.org/toc/24_2 Last accessed 16. 06. 2017.

True, Jacqui. 2003. Gender, Globalization, and Postsocialism. New York: Columbia

University Press.

1This article was supported by the János Bolyai Research Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, and by OTKA 112700 Space-ing Otherness. Cultural Images of Space, Contact Zones in Contemporary Hungarian and Romanian Film and Literature.

[1] Or if they refer to tragic and traumatic Hungarian past after all, they do it in symbolic or metaphoric way. (cf. Kalmár 2013; Strausz 2011)[2] Cf. Kalmár localizes the space of exile on the border of life and death. Mihail, returning to the Danube Delta positions his shelter on the water as a non-place, which belongs to the realm of both life and death. He writes “However, this new place is on the water, a symbolic element that stands just as much for death as for new life at least since Ulysses decided to head back to Ithaca. The ambiguity of the project and the place of retreat (as a figure of both life and death) is emphasised by several details.” (Kalmár 2017, 19)