András Hlavacska

Can Freud Cure Vampires?[1]

Therapy for a Vampire from the Perspective of Dracula’s Psychoanalytic Readings (download pdf)

hlavacskandras@gmail.com

Abstract. A common feature of the Dracula (1897) studies is that they always search for figurative meaning in the text. Most Dracula analyses replace the different segments of the story (for example the vampires, the vampire attacks, the transfusions of blood, etc.) with something else: for them these elements always point at another meaning. Although it would be an exaggeration to claim that the psychoanalytic readings established this method in the Dracula research, however there is no doubt that these analyses used it first in a comprehensive manner. In the last fifty years the psychoanalytic reading of Bram Stoker’s novel has been the subject of many debates: some confirmed, others denied its validity – and in the meantime the psychoanalytic interpretation became an inevitable part of the Dracula research. However, the psychoanalytic readings have no sole responsibility for the figurative interpretation of vampires: ambiguity was present for a long time in the popular culture based on Dracula – especially in cinema. Contemporary vampire movies have to take into account this psychoanalytic heritage: in my essay I would like to shed light on how Therapy for a Vampire [Der Vampir auf der Couch, 2014] deals with this heritage.

Keywords: Dracula, vampires, psychoanalytic readings, metaphorical interpretations, sexuality, David Rühm, Bram Stoker

There is no doubt that amongst the various theoretical approaches of Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) the most numerous and the most influential are the psychoanalytic readings. The first psychoanalytic interpretation of the novel was written in 1959 by Maurice Richardson (The Psychoanalysis of Ghost Stories). In the 1970s and 1980s many critics analysed the Dracula from the same point of view (Welsch 2009, 41–45). Yet from the 1990s these kinds of interpretations provoked sharp criticism: the Dracula research turned its attention towards the historical, ideological, cultural, technical, etc. context of the novel (see Arata 1990, 635; Spencer 1992, 197; Highes 2000, 3–4; Aikens 2009, 42). Mathias Clasen’s study is an example (perhaps the most explicit one) of this change: “enough with the talk of »bleeding vagina[s]« and evil mothers already. Dracula scholars would do well to leave Freud and his followers behind” (Clasen 2012, 380). However, contemporary vampire movies show just the opposite: they are proof of the persistence of Dracula’s psychoanalytic readings in the 2010s.

The Therapy for a Vampire [Der Vampir auf der Couch, 2014] directed by David Rühm epitomises this approach. A free adaptation of Dracula, its plot is far from the original novel’s story. However, the movie makes numerous references to the novel and its heritage. The vampire Geza von Közsnöm, one of the main characters, always recalls with great joy his relation with Romania, Hungary and Transylvania, all significant places in Stoker’s novel. Lucy, the name of another main character in the movie also turns up in Stoker’s novel. The action of the movie takes place in 1932 – just one year after the premier of the famous Dracula adaptation directed by Tod Browning. But what makes Therapy for a Vampire really interesting for the Dracula research is its affinity with psychoanalysis: the movie could be easily interpreted as a reflection of the relationship between vampire stories and Freudian psychoanalysis. For this very reason I will focus on the various psychoanalytic readings of Stoker’s novel reflected upon in the film in question.

Maurice Richardson’s statement („[only] from a Freudian standpoint – and from no other – does [Dracula] really make any sense”) (Richardson 1959, 427) and Mathias Clasen’s aforementioned reflection on this represents the two opposite poles detectable in the researchers’ approach to psychoanalytic readings of Dracula. While many studies written after Richardson’s essay proved that Stoker’s novel can be interpreted from different perspectives, Therapy for a Vampire and similar movies make it clear that the psychoanalytic readings cannot be disregarded once and for all.

In my analysis I will emphasise one of the features of the psychoanalytic readings – namely the metaphoric interpretation of the novel. The Dracula studies’ common feature is that they always search for figurative meaning in the text. Most Dracula analyses replace the different segments of the story (for example the vampires, the vampire attacks, the transfusions of blood, etc.) with something else: for them these elements always point at another meaning. Although it would be an exaggeration to claim that the psychoanalytic readings established this method in the Dracula research, however there is no doubt that these analyses used it first in a comprehensive manner. C. F. Bently sees the vampirism as “a perversion of normal heterosexual activity” and the blood fusion as a symbol of sexual intercourse (Bently 1972, 29); Phyllis A. Roth reads the female characters’ transformation into vampire as the awakening of their sexual desire (Roth 1977, 114–115); Alan Johnson argues “that the novel’s form is largely determined by its presentation of the vampire Count Dracula as a literary double for the unconscious or only partly conscious rebellious egoism experienced first by Lucy and then by Mina in reaction to the constrains and condescension which have been inflicted on them by their society.” (Johnson 1987, 20) and for Christopher Craft the vampires blur the conventional Victorian gender categories (Craft, 1999, 93–118). We could continue the list, but these examples sufficiently exemplify the psychoanalytic interpretations of the novel. In the last fifty years this perspective has been the subject of many debates: some confirmed, others denied its validity – and in the meantime the psychoanalytic interpretation became an inevitable part of the Dracula research. In 2006 Elizabeth Miller already wrote that it is hard to “imagine a Dracula in which wooden stakes are wooden stakes, and blood is merely blood.” (Miller 2006)

But the psychoanalytic readings have no sole responsibility for the figurative interpretation of vampires: ambiguity was present for a long time in the popular culture based on Dracula – especially in cinema. To take just one example: in Roman Polanski‘s horror-comedy, the Dance of the Vampires; The Fearless Vampire Killers, Or Pardon Me but Your Teeth Are in My Neck (1967) vampirism and vampire attacks obviously have a sexual overtone. In the first half of the movie vampires attack young women only when they are naked or half-naked. These attacks in itself would not have been significant, but later events in the castle shed new light on them. For example, at their first encounter in the castle, Herbert, the homosexual son of the vampire count Krolock, shows his affection towards Alfred, the young vampire hunter. Later Herbert attacks Alfred [Figs.1–4.].

The scene where Sarah uses the bathroom next to Alfred’s room is also a striking example that vampire attacks have sexual overtone. Alfred finds himself in a dilemma: he really likes to peep Sarah through the keyhole, but his conscience does not allow him to do it. This is when Count Krolock turns up – as if he would be the manifestation of Alfred’s desires – and does what the young vampire hunter would like to do: first he peeps Sarah through the skylight, then flies into the bathroom, bites her neck and runs away with her [Figs.5–8.].

Alan Johnson in Bent and Broken Necks: Signs of Design in Stoker’s Dracula mentions many other novels from the 19th century in which a character is presented as a – usually evil or immoral – double of a main character. As Johnson writes: “the second-self character enters the narrative at just the point when the central character is, or supposed to be, feeling or thinking what the second character personifies.” (Johnson 1987, 20).

The last example is important for the psychoanalytic readings of Dracula for two reasons. On the one hand, it shows how the central theme of the psychoanalytic interpretations, sexuality, lives on in a vampire movie closely related to Stoker’s novel. On the other hand, it illustrates that the main method of the psychoanalytic analyses, the metaphorical reading can be applied both in the novel and in its cinematic heritage.

The Therapy for a Vampire has an ambivalent relation to the psychoanalytic interpretations of Dracula and the metaphorical readings. At first sight it may appear that the movie parodies both these analyses and the methodology. At the beginning of the movie Geza von Közsnöm visits Freud and asks for his help. Once during the treatment the Count talks about his dead lover. Suddenly he quotes from the 4th chapter of Totem and Taboo: “»We know that the dead are mighty rulers«”. Then Freud says that this is a misinterpretation of the sentence, but Közsnöm replies: “The true meaning of this sentence hasn’t been grasped yet. Maybe you underestimate its depth yourself.” This comical scene – a vampire explains the true meaning of the Totem and Taboo to its author – becomes even funnier if we associate it with the psychoanalytic readings of Dracula. In the Dracula research time and again the question arises to what extent the “design” of Stoker’s novel was intentional. Some argue that Stoker intentionally wrote an erotic, quasi-pornographic novel, while others on the contrary describe him “as an author unconscious of the essential nature of his novel” (see Johnson 1987, 18).

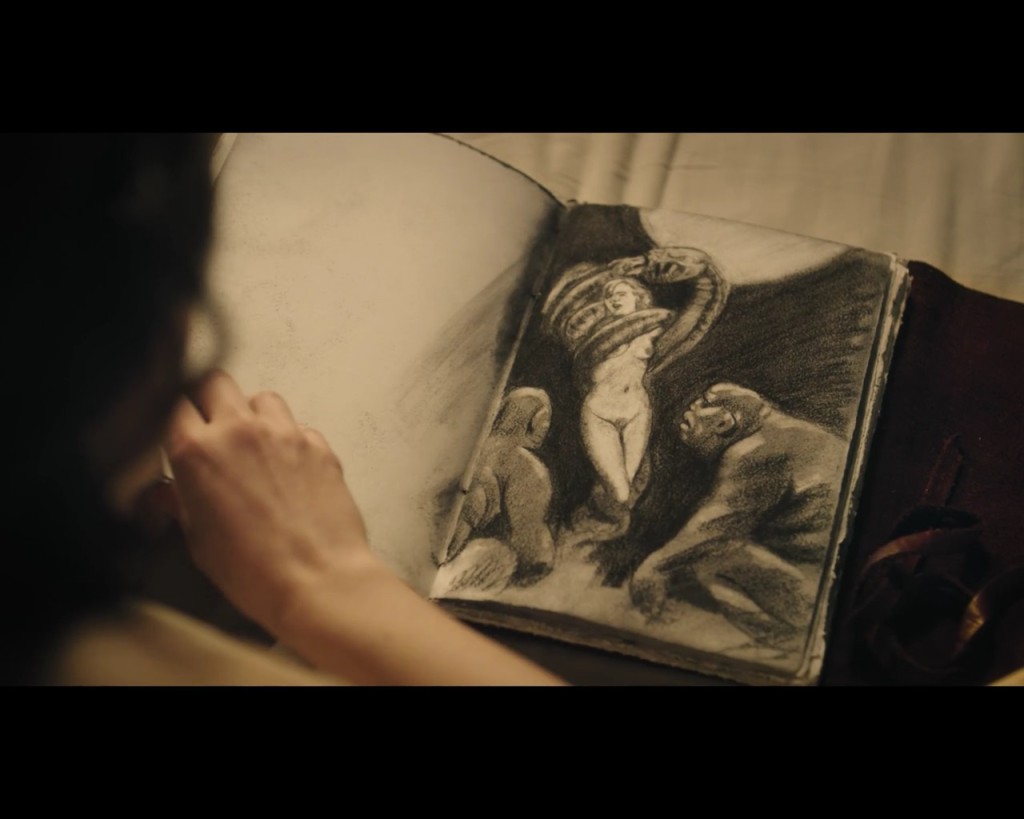

In the movie Geza von Közsnöm gives Freud a taste of his own psychoanalytic therapy, and shows that the meaning of a sentence cannot be determined by the author’s intention, rather by the reader’s interpretations. The movie also parodies the psychoanalytic interpretation of monsters appearing in dreams. At the beginning of the story Freud asks his friend, Victor, to draw his patients’ dreams. The scene takes place as follows: Freud is lying on the sofa and he is reading his notes (“Then the tree turns into a hybrid creature of a wolf and man. The young damsel is now lying in a cave on a big rock, and the mythical creatures lurk around her with excitement. She feels lust and guilt at the same time.”), while Viktor is drawing in a sketchbook. Suddenly Viktor interrupts Freud and says that these dreams “could interest a wider audience.” But Freud replies without hesitation that all these cases must be handled with absolute discretion. “Discretion” and “lust” strongly suggest that these dreams about mythical monsters have a sexual characteristic. (Later when Victor’s girlfriend, Lucy looks into the sketchbook in secret, we can see that Victor has drawn the dreams like erotic images) [Figs.9–10.].

Thus the movie emphasises that, from the Freudian psychoanalytical perspective, monsters – such as wolf men, minotaurs, vampires, etc. – always have a sexual overtone. In the Dracula scholarship it is not uncommon that a psychoanalytic reading is based on this assumption: it neglects the context or the description (of the monster) and – referring to psychoanalytic experiences – takes for granted that events associated with vampires have sexual meaning, which only should be confirmed with a closer look of the text or the scene (see Bentley 1972, 27). Contrary to this approach, the movie reveals the importance of the context. It not only presents sketches of monster-dreams, it also provides insight into such a dream. One night Geza von Közsnöm helps his pickled wife, Elsa to lie down. Then he sits down beside her coffin and holds her hand until she falls asleep. But once his wife is asleep he leaves the crypt. However, shortly afterwards we see him again sitting near his wife’s coffin. He looks at his wife with loath and hate, takes a sharp wooden stake, places it right over his wife’s heart, and strikes it with a hammer. Next the Count is startled awake in his car and it becomes clear that he only dreamed the previous scenes [Figs.11–13.].

To strike a wooden stake into the heart of a vampire is a well-known method of destroying an undead; therefore the scene can evoke not solely the Dracula but many different vampire narratives. However, in some elements of Geza von Közsnöm’s dream we can easily recognise a similar episode from Stoker’s novel. In that chapter the vampire hunters – led by Van Helsing – destroy Lucy Westenra, a young vampire. Arthur Holmwood, Lucy’s fiancé must execute this terrible act; he strikes the stake into her heart. This episode became a cornerstone of Dracula’s psychoanalytic readings: researchers supporting the sexual interpretation never miss to quote it. For example C. F. Bently claims, that “[t]he methods used to destroy vampires also contain sexual implication […]. Lucy, who becomes a vampire after succumbing to Dracula’s attack, is released from her »undead« state into true death by her erstwhile fiance Arthur, who drives a hardened and sharply pointed wooden stake through her heart. The phallic symbolism in this process is evident” (Bentley 1972, 31).

Yet there is no sexuality in Geza von Közsnöm’s dream. The movie – with the crypt scene – evokes Stoker’s Dracula and its psychoanalytic readings and – by Victor’s sketches – also refers to the reference framework of these readings. However, the only monster-dream in the movie does not imply any sexual symbol. The movie sends a clear signal: it is fully aware that vampire stories could have sexual meanings, but at the same time it claims that these are not always relevant.

Therapy for a Vampire mocks the associations which connect vampirism (blood sucking) to sexuality. There are two scenes in the movie where a character misunderstands bloodsucking because he interprets it as a sexual act. Towards the end of the movie Elsa bites and transforms Victor’s girlfriend, Lucy into a vampire. Geza von Közsnöm tries to protect Lucy so he takes her under the supervision of Freud and lays the unconscious girl down in the doctor’s bed. Shortly afterwards Freud – who has taken sleeping-pills earlier – also falls asleep. Lucy waking up in the middle of the night experiences strange changes on herself: her sensory system becomes extremely sensitive; she hears the blood pulsing in the professor’s jugular vein loudly. She cannot resist the temptation, she bites Freud’s neck and starts sucking his blood. In this very moment Victor wakes up in the room next door. He hears voices from the doctor’s room so opens the door and catches sight of Lucy pressing her lips tightly to the doctor’s neck [Figs.14–17.].

It is a strongly ambiguous scene – not a surprise that Victor misunderstands Lucy’s act: LUCY: “Something crazy has happened.” VICTOR: “I can see that. You, in his bed? […] That old geezer? […] Why are you in his bed? […] What are you doing in his bed?” However, in a later scene it is Lucy who misunderstands Victor’s words. When she asks the painter about the nature of his relation with Elsa, and Victor replies that Elsa “just drank my blood”, Lucy is shocked by this answer (“That’s pretty intimate!” – she says). Therapy for a Vampire shows that sometimes we misunderstand the situations if we interpret blood sucking as a sexual symbol – as it was the case of the monster-dream.

The movie not only parodies the psychoanalytic readings but generally mocks all metaphorical interpretation. It is most clearly represented in the conversations of the vampire Count and Freud, but other episodes of the movie also confirm this assumption. At their first encounter, Geza von Közsnöm says to Freud: “I’m not good at self-reflection. I need your help. […] There’s nothing left for me to discover. […] My blood flows languidly and cold through my veins. I’m fed up of this everlasting night. This eternal darkness, swallowing me up. I long for light. Bright light, where I can disappear and dissolve.” The viewer – who already knows that the Count is a vampire – perhaps finds this scene comical because he understands the ambiguity of these sentences. But Freud does not observe the Count from this point of view; he tries to interpret what he heard with his own psychoanalytic theory. Towards the end of the movie, he displays the same attitude when Victor wakes him up in the middle of the night. “She’s [Elsa] a vampire, an undead. She has no reflection, I saw it.” – the painter says. It is obvious that Victor needs immediate and urgent assistance but he only gets a big dose of sedative from Freud. The message of these scenes seems clear: sometimes we do not need to interpret the vampires’ existence, just accept them as they are: vampires, bloodsucker monsters. This is the only way to help them or those who fight against them. If we search for a figurative meaning we find nothing.

Two other scenes of the film demonstrate the same perspective. In Victor’s apartment the artist is about to paint Elsa when the vampire woman steps closer to him and whispers into his ear: “If you manage to paint me, you’ll become immortal.” As in the case of Közsnöm’s monologue quoted above, only the viewer can perceive the ambiguity of the sentence. Victor – since he does not know that Elsa is a vampire – only could think that the painting will make him famous. He cannot suspect Elsa’s covert offer (if he paints the vampire woman she transforms him into an immortal bloodsucker).

In the second scene the same characters are having a dinner in a restaurant. When Victor orders stake with garlic sauce, Elsa immediately interrupts him saying that they do not need the garlic sauce. Victor first seems confused but then breaks into a smile: “Who knows what the night will bring.” For the viewer (as in the last scene) it is obvious that Elsa was misunderstood: she does not refuse the garlic sauce because she has an intimate plan for the night but because she – being a vampire – hates it. The conclusions of the scenes are similar: Victor could only understand Elsa if he saw her true identity, her vampire-self.

Nevertheless, many features of Therapy for a Vampire make the parodic interpretation of the movie uncertain. It is very revealing that the vampire goes to Freud and not the other way round. As I mentioned above, when Freud asks Geza von Közsnöm what the purpose of his visit is, the vampire replies: “I’m not good at self-reflection. I need your help.” The ambiguity of the first sentence is clear for everybody who is familiar with the vampire lore: it refers to the “disability” of the vampires that they have no reflection in the mirror. If we know this, the vampire’s answer to Freud could easily mean that he looks for practical and not psychological help. However, in this case he would have certainly visited someone else, not Freud: this is made clear in the movie with Elsa’s story – when a vampire needs practical help he or she goes to a painter.

The narcissistic Countess wants to see the image of her face at any cost, as she would like to know how she really looks: at the beginning of the movie she asks her husband to give a detailed description of her face. Later we see her in front of a mirror applying a lot of makeup powder because she expects to see her face in the cloud of the powder [Figs.18–19.].

When she finally asks for external assistance she has no intention to visit a psychiatrist, rather she hires a painter. If Geza von Közsnöm would have the same kind of problem, he would probably act similarly. So the fact that he visits Freud suggests that the nature of his problem is of different nature and he thinks that Freud could help him. It is clearly not the case that Freud completely misunderstands the vampire during the therapy – just as Victor misunderstands Elsa –, but rather that Geza von Közsnöm uses ambiguous expressions on purpose: he is aware that the primary meaning of them is not understood by the doctor, however he wants to know how Freud interprets them. The therapy is not a game at all for the vampire: he does not go to Freud to mock him, rather he would like to see how someone not knowing that he is a vampire interprets his existence – he simply wants to increase his self-awareness through the therapy. In short, he would rather like to understand how a psychologist interprets the vampire existence with psychoanalytic method. The fact that Geza von Közsnöm does not reveal his vampire identity during the therapy – even when Freud asks about it – demonstrates this assumption. Talking with the doctor about his ex-lover, Nadila, Geza von Közsnöm claims, that “[s]he made me what I am today.” This sentence has a connotative meaning: it could mean that Nadila transformed the Count into a vampire. However, when Freud asks what he is today, the vampire’s response is evasive: “That’s why I’m here. I’m not myself. Or what I used to be. That’s my problem.”

To sum up, Therapy for a Vampire parodies the Dracula and its psychoanalytic readings. Many scenes suggest that sometimes if we try to interpret metaphorically the vampire stories, we easily misinterpret them. However, it would be misleading to state that the movie generally parodies the metaphorical interpretations. While Therapy for a Vampire usually mocks these kinds of approaches, it cannot be disregarded that sometimes the movie itself uses strong metaphors – and wants us to recognise them.

The best example of this is a scene at the beginning of the movie where Lucy has a fight with Victor. At the end of the scene Lucy storms out from the apartment and Victor slams the door. In the next moment the movie shows a withered bouquet which – due to the slammed door – loses its last petal [Figs.20–21.].

Earlier we saw that Victor gave this bouquet to Lucy. The bouquet and the falling petal clearly indicate that their relation came close to an end. The image of the withered bouquet is an example of the film’s visual metaphors; we could understand this conventional metaphor as a signal towards the viewers: Love is a Flower is a classical metaphor, most of the viewers will note it. Thus the movie with this metaphor not only makes the changes in the relation between Lucy and Victor more tangible, it also draws attention to its own figurativity, calling out for a complex interpretation.

References

Aikens, Kristina. 2009. Battling Addictions in Dracula. Gothic Studies. vol. 11 no 2: 41–51.

Arata, Stephen D. 1990. The Occidental Tourist: Dracula and the Anxiety of Reverse Colonization. Victorian Studies. vol. 33 no. 4

(Summer): 621–645.

Bently, C. F. 1972. The Monster in the Bedroom: Sexual Symbolism in Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Literature and Psychology. vol. 22 no. 1:

27–34.

Clasen, Mathias. 2012. Attention, Predation, Counterintuition: Why Dracula Won’t Die. Style. vol. 46 no. 3–4: 378–398.

Craft, Christopher. 1999. ‛Kiss me with Those Red Lips’: Gender and Inversion in Bram Stoker’s Dracula. In Dracula, ed. Byron Glennis,

93–118. London: Macmillan Press.

Highes, William. 2000. Beyond Dracula: Bram Stoker’s Fiction and its Cultural Context. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Johnson, Alan. 1987. Bent and Broken Necks: Signs of Design in Stoker’s Dracula. Victorian Newsletter. no. 72 (Fall): 17–24.

Miller, Elizabeth. 2006. Coitus Interruptus: Sex, Bram Stoker, and Dracula. Romanticism on the net:

https://www.erudit.org/revue/ron/2006/v/n44/014002ar.html, accessed 2016. 01. 07.

Richardson, Maurice. 1959. The Psychoanalysis of Ghost Stories. Twentieth Century. vol. 166 no. 994: 419–431.

Roth, Phyllis A. 1977. Suddenly Sexual Women in Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Literature and Psychology. vol. 27 no. 3: 113–121.

Spencer, Kathleen L. 1992. Purity and Danger: Dracula, the Urban Gothic, and the Late Victorian Degeneracy Crisis. ELH. vol. 59 no. 1

(Spring): 197–225.

Welsch, Camille-Yvette. 2009. A Look at the Critical Reception of Dracula. In Dracula: Critical Insights, ed. Jack Lynch, 38–54. Pasadena:

Salem Press.

[1] This work was supported by the project entitled Space-ing Otherness. Cultural Images of Space, Contact Zones in Contemporary Hungarian and Romanian Film and Literature (OTKA NN 112700).