Rites of Retreat in Contemporary Hungarian Cinema[1] (download pdf)

György Kalmár

Abstract: On the basis of three Hungarian films of the last decade, the present paper investigates a special sub-category of so-called “return films” (Gott and Herzog 2015, 13), one that I will hypothetically call retreat films. In these films returns become ritualistic retreats with masculinities on “regressive journeys” (Király 2015, 170; see laso Sághy 2016; Sághy 2017). Their spatial trajectories may typically lead from Western cultural centres to Eastern homelands, from cities to the countryside, from the public sphere to the private, sometimes symbolically from the future to the past, and often from the realm of desire to that of Thanatos. The men of these films tend to struggle to find places of their own on the margins of society, away from public spaces: what they seem to have in mind is a place to hide, somewhere to retreat, that is, a closet of their own.

Keywords: Hungarian films, return, retreat, masculinity, crisis

Introduction: Shifting Trajectories

One revealing aspect of recent Eastern European gender politics (and Eastern European history in general, for that matter) is that “return films” have become an important group of post-1989 Eastern European cinema (see: Gott and Herzog 2015, 13). Apparently, many male protagonists of post-communist Hungarian cinema tend to return from their westbound journeys, often so as to withdraw from the open, public (traditionally masculine), usually urban spaces of self-liberation, from the possibilities of establishing more authentic, publicly accepted identities, thus creating unusual spatial patterns and peculiar masculinities. As Hajnal Király argues in a recent paper that my present research is much indebted to:

In Hungarian and Romanian films of the last decade, the central dilemma frequently revolves around mobility, that is, whether to stay or move on, whether or not to leave (the country, the family, a traumatic situation, a beloved person, or ultimately life), which frequently escalates to a deep existential crisis and which signals the ultimate impossibility of either staying or moving on/leaving. Places and spaces performed by bodies in distress become sites of a dysfunctional society, often revealed in the narrative of an aborted, circular, interrupted or regressive journey. … Additionally, many Hungarian and Romanian films feature characters who return from Western Europe, only to realize that home is not an ‘authentic’ place anymore… (Király 2015, 170)

The present paper investigates a special sub-category of these “return films,” one that I will hypothetically call retreat films. I am going to focus on three Hungarian films of the last decade: Taxidermia (György Pálfi, 2006), Delta (Kornél Mundruczó, 2008), and Land of Storms (Viharsarok, Ádám Császi 2014). In these films returns become ritualistic retreats with masculinities on “regressive journeys.” Significantly for the purposes of the present study, all three films present male protagonists in some kind of crisis, and the drama of these crises are played out in spatial terms. The spatial arrangements and movements found in these films may be analysed as ritualistic retreats, where (usually as a result of some kind of frustration or trauma) characters turn their backs on mainstream identity-formations and the associated desires, and withdraw into secluded places so as to hide, heal, find their way back to their roots, or simply die. Their spatial trajectories may typically lead from Western cultural centres to Eastern homelands, from cities to the countryside, from the public sphere to the private, sometimes symbolically from the future to the past, and often from the realm of desire to that of Thanatos. The men of these films tend to struggle to find places of their own on the margins of society, away from public spaces: what they seem to have in mind is a place to hide, somewhere to retreat.

Clearly, these films and the spatial movements of their male protagonists cannot be fully understood without the “profound disillusionment” (Shaviro 2012, 25) experienced in Hungary not long after the fall of communism, without “the problematic and largely unfulfilled fantasies of integration and redemption that have accompanied Hungary’s so-called ‘return to Europe’” (Jobbit 2008, 4). Today, twenty-five years after the fall of communism, it is clear that Eastern Europeans had much distorted, idealised views of the West, that is, of consumerist liberal democracies, as well as of their chances of turning into such a society from one day to the other. They (or rather we) were wrong about both issues: transforming a society (together with people’s attitudes) takes a long time, (totalitarian) history is not so easy to leave behind, and even if we do manage to change, consumerist liberal democracies are not necessarily the “culmination of all human effort and hope” (Shaviro 2012, 26). As Gáspár Miklós Tamás argues, the regime change in Eastern Europe led to “an inhuman, unjust, unfair, inefficient, anti-egalitarian, fraudulent, and hypocritical system that is in no way at all superior to its predecessor, which was awful enough” (Szeman and Tamás 24). I would argue that this “atmosphere of disillusionment and demoralization” that Shaviro also considers to be a key background to the film Taxidermia (26) has shaped Eastern-European masculinities and the spatial journeys they take (see also: Sághy 2016; Sághy 2017).

Apparently, the history of gender has unpredictable turns in Eastern Europe, ones leading away from the Western liberal narrative of gradual liberation and self-fulfilment in a consumerist democracy. For men of the third millennia to find themselves in Virginia Woolf’s 1929 shoes must come as a shocking surprise. Yet, apparently, some room (or place) of one’s own was not only important for women in 1929: the films under analysis imply that being a woman is not the only form of marginalised subjectivity, and the 2000s are not as much fun as we thought they would be. In these Hungarian films men as well – all sorts of them, white and coloured, straight and gay, bastards and orphans, artists and sportsmen, migrants and catatonic – may find themselves homeless in the “new Europe”. The dream people had under state-socialism, the dream of freedom, happiness and self-realization is over: these men have seen democracy and consumerist capitalism, many of them have even tried their luck in the West, yet they have all turned back, bitter and disillusioned, towards the past, their (real or imaginary) roots, the local Eastern home(less)land, or plainly death, the ultimate goal of such regressive journeys. Their narratives are typically not victorious stories of liberation and acceptance (coming out of the closet), but rather those of retreat, hiding, escape and exile. They are all defeated in their own ways, usually even before the film’s narrative begins. What we see is already plan B (or C or Z), the last resort, the last try to be someone, someplace.

The protagonists of the above mentioned films are clearly and markedly different from the privileged types of contemporary Hungarian society. Their masculinities are reactionary and regressive, based on the rejection rather than the legitimization of the dominant patriarchal culture. In the context of the films’ narratives the pale, anorexic taxidermist Lajoska of the last episode of Taxidermia (which I will analyse), Mihail, the silent, mysterious hero of Delta, who comes home from abroad so as to build a log-house in the Danube Delta with the help of his sister-lover, or the gay failed footballer of Land of Storms returning from Germany to conservative rural Hungary, are all cinematic examples of non-hegemonic masculinities (see: Connell 2005, 76). The difference or distance from hegemonic, normative gendered and racial identities often appears in these films through spatial arrangements, as distance from human communities and settlements. These male characters try to establish a room or place of their own, a habitat, a home, where their dishevelled embodied identities can take place.

What we see in these films can be read as spatial renegotiations of selfhood, or desperate relocations of embodied identity, where such issues are at stake as national belonging, personal dignity, relating to one’s roots, finding spaces in which one’s preferred sexuality can be practised, establishing an accepting, caring relationship with others, feeling at home in the world, creating a habitable place where one is accepted and loved, escaping fields of defeat and frustration, or at times simply survival. Cultural geography’s Lefebvrean-Foucaldian axiom that “geography matters, not for the simplistic and overly used reason that everything happens in space, but because where things happen is critical to knowing how and why they happen” (Warf and Arias 2009, 1) goes at least as much for cinema as for ordinary social phenomena. In other words, “the geographies become vital: far from being incidental outcomes of power, they become regarded, in their ever-changing specifics, as absolutely central to the constitution of power relations” (Sharp et. al. 2000, 25).

In what follows I am going to analyse the three films one by one from the above outlined perspective, following a chronological order of their making.

Taxidermia

Taxidermia is the art of mounting, turning once living, now dead bodies into mummies, artworks or bodily memorials. Taxidermia can be an allegory of the film itself: not only á la Bazin, who thought that filmmaking in general is driven by the urge to mummify the living and preserve it in dead, celluloid form, but also because Pálfi’s film tells the story of three generations of Hungarian men, all defeated and dead by the time of the act of storytelling (see: Bazin 2005, 9-10).

All three generations are characterised by the spatialised mechanisms of defeat and retreat. “Each part juxtaposes the private and the public: a body horror case study in imploding masculinity is joined with a parody of the spectacles of power and privilege” (Shaviro 2012, 26). The grandfather Morosgoványi, the halfwit orderly living a debased, subhuman life at an army outpost during World War 2 is clearly a loser, who is trained, ordered around and humiliated on a regular basis by the lieutenant he serves. He is also isolated and confined (see: Shaviro 2012, 26-27, Strausz 2011, 2): not only to the outpost in the middle of nowhere (the whole episode takes place on a few hundred square meters), but also to the little wooden shack next to the pig-sty and the loo, outside the house. The father’s life is not much better: he is a fast-eating almost-champion, living and competing (in this imaginary sport) in state-socialist Hungary. His story is another failure narrative: first we see him fail at a competition (his jaw gets locked in the final moments of the competition – a meaningful bodily metaphor in the present context – after which he faints), then we see him being cheated on at his wedding night, not having the money to make the operation that helps sportsmen of other nations, and not making it to the West where he thinks he could be a star. By the time of Lajoska’s story he is confined to a small apartment. He is so grotesquely overweight that he cannot even move: it is Lajoska who changes the pot under him and brings the enormous amount of food that he and his huge, trained cats consume. Now he is not simply locked up behind the iron curtain, but also in his huge body and in this small apartment that smells of urine and excrement.

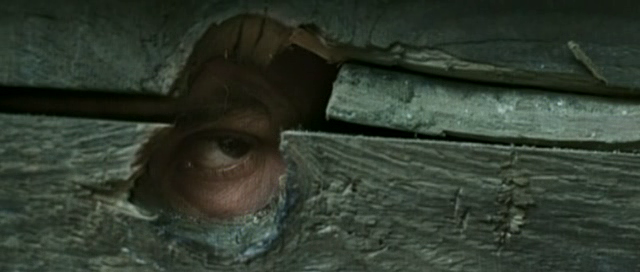

Both Morosgoványi and Kálmán have lost the most important battles of their lives, and are forced into exile. As László Strausz argues in the context of embodied memory practices, “Morosgoványi is repressed and he creates a secular bodily mythology and retreats into a private world. Eating for Balatoni is a sport that allows him to escape the repressive bounds of the system, although his body becomes seriously disfigured in the process” (Strausz 2011, 3). Moreover, both the little shack and the apartment in Budapest seem small, dirty, and confining, spaces for sub-human existences without dignity or love. Both characters’ solitude and frustration are expressed through visual and spatial symbols. Morosgoványi’s main hobby and passion is to peep at the officer’s daughters, two young and beautiful women living in the house. He watches them through the window of the house or through the holes in the wooden planks that separate him from “proper” human beings (see: [Fig.1.]), while often masturbating (see: Strausz 2011, 2). Kálmán’s confinement is also emphasised by a poster of a seaside resort behind him on the wall (a common and ironic phenomenon of state-socialist building block apartments). In his case it is the TV that fills the function that the window and the holes in the walls did in case of the Morosgoványi part: during his son’s daily visit (when he brings the food, and empties the pot), Kálmán usually watches a video recording of an American fast-eating competition. While he is boasting to his son how better he would do than these “losers” and “arseholes”, we notice his ex-wife, Gizi in the video, supporting or coaching one of the competitors. The motif of the first episode is clearly repeated: Kálmán watches Gizi and images of sports success similarly as his father Morosgoványi watched the unreachable young women through the window and the plank wall. Both are separated from their dreams, and both fail when they try to surpass their limitations. One telling, spatially arranged and highly symbolic representation of this situation is the scene when Morosgoványi watches the two young, joyful women’s snowball fight outside his shack. He gets aroused at the sight and starts masturbating: he finds a hole in the wall, coats it with lard, pushes his penis through it, “thrusting it frantically in and out” (Shaviro 2012, 27). His sexual practice can be seen as an attempt to exceed the limitations of his life, to go past the borders that separate him from his objects of desire. Significantly, the scene ends before he could reach orgasm, when a rooster (a markedly gendered agent of power) notices his penis on the other side and pecks at it…

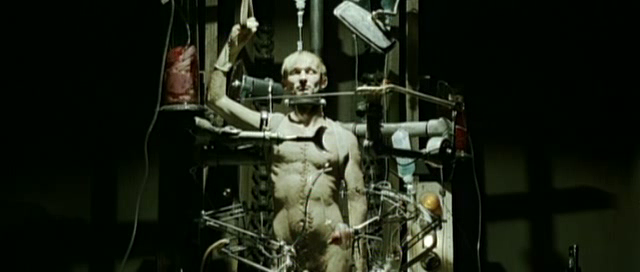

This pattern changes somewhat when the film gets to the story of the Lajoska. The genre of the family novel already ascribes him, as the member of the third generation, a position of degradation: in the novelistic tradition this is a time of the fall of the family with the appearance of artist figures to record the stories of the past generations. Taxidermia seems to follow this pattern: Lajoska’s story starts with the picture of a pigeon’s back side, from which shit falls to the pavement in front of the taxidermist’s entrance. The camera moves from the white stain through the door, into the house, through the claustrophobic corridors of the workshop decorated with hundreds of furs and stuffed animals, till it finds him, pale and thin, working on a huge bear. From the beginning, Lajoska is associated with white: the baby’s clothes in the hospital before the camera goes through the window to the pigeon, the bird’s excrement, the tiles in the workshop, and his almost albino-like skin. However, in Taxidermia white is not the colour of purity, but rather that of a bloodless, lifeless body, a meaningless life, a traumatised subjectivity and death. Lajoska lacks the sexual passion of his grandfather (he does not have a partner, he fancies a pretty cashier woman in the supermarket whom he ineffectively courts by shyly handing over a lollipop each time he pays for his father’s supplies), but he also lacks the superhuman appetite of his father (he is skinny as an anorexic, and we never see him eat during the film). I would argue that Lajoska’s obsession with dead things, as well as his lack of sexual desire and appetite can be read as physical forms of resistance to the paternal order, a practice of self in defiance of the qualities, ideologies and identity-formations of his fathers.

From the three generations of men Lajoska is the most emblematic figure of the motifs of retreat, confinement and escape, as there is no outside power forcing him into exile. No visible “outside” factor destines Lajoska to live his life surrounded by dead things in his cold, literally lifeless labyrinthian den. The film suggests that his miserable existence is only due to opaque psychological reasons, or the weight of the family history on his shoulders (see [Fig.2.]).

The spaces of his life and his bodily practices are most informative: each day he goes through the same routine: he works in his taxidermist workshop (apparently he also lives there, though we never see any furniture hinting at that), he buys food for his father (always the same quantities of margarine and chocolate), hands over the lollipop to the cashier girl, has a coffee alone in the hall outside the supermarket, and visits his father to clean and feed him and his cats. All these spaces appear empty, cold and lifeless, and all these activities seem joyless repetitions. His life is without passion, his body is pale as that of dead people. He never laughs, eats or has sex, his work is the art of death and mummification, so when the spectator glimpses at his suicidal self-mounting machine, one is not very surprised. His regressive journey through his den of death towards self-mounting is foreshadowed by his last work, the tiny human embryo he mounts for the narrator. I would argue that this small object may be interpreted as a visual metaphor standing for his regressive subjectivity. This figuration could entail seeing his place of retreat, the partly subterranean den of death as a womb, as the non-place of the pre-Oedipal mother, where Oedipal subjectivity is dissolved in something greater and more primordial.

As we have seen, none of the three men in Taxidermia manage to overcome the confining difficulties of their lives, all escape into meaningless bodily activities (Strausz 2011, 3), such as sex without a partner or reproduction, eating for the sake of eating, stuffing and collecting dead animals only to eventually become one of them. Marosgoványi and Kálmán had a view of what they wished for, only they could never reach it. Lajoska, on the other hand, lacks any view of happiness, he has been lost all along and does not even seriously try to escape these spaces of retreat and exile.

Delta

The regressive movement towards death may be less apparent in Kornél Mundruczó’s Delta (2008) than in Lajoska’s story in Taxidermia, but it is just as essential for the coherence of the plot and the motivation of the main character. The film tells the story of the homecoming of a prodigal son, Mihail (Félix Lajkó). He does not collect dead animals as Lajoska, nor is he pale and anorexic-looking: he would simply like to build a log-house on the river in the astonishingly beautiful and untamed wetlands of the Danube Delta (where his father used to have a fishing hut), so as to hide away from the world. “Mihail looks fragile, shy and stylish in his cord velvet jacket, a trademark of the Western bohemian. Significantly, his character is played by Félix Lajkó, an ethnic Hungarian violin virtuoso from Serbia” (Király 2015, 179). Mihail has been to the West, as his banknotes also reveal, he has travelled the world and is back now. Yet, in this Eastern European version of the prodigal son, there is no loving father to welcome him. The remains of his family, his mother (Lili Monori), sister (Orsolya Tóth) and his mother’s tyrannical, bad-tempered lover (Sándor Gáspár) live in a nearby village, in physical and emotional deprivation. They run the local pub, a run-down place for faces well-known from Tarr’s films. When his mother asks him how long he wants to stay, he does not answer. Apparently, he has come back for good.

We do not learn the reason of either his leave or his return: these details of the story (as many others) are left in mystery. What matters in Mundruczó’s poetic and almost mythical piece is beyond or beneath such practical or rational details. His return is simply inevitable, just as his leave was. His slightly disturbed, traumatised look and silences, his need for solitude and pálinka (home made, strong brandy) all talk about a troubled past, but that is taken for granted in this tradition of Eastern European art-house cinema reminiscent of Béla Tarr’s works. Return and repetition – as Freud so famously theorised apropos of war neurosis (what we call PTSD today) in Beyond the Pleasure Principle – are intimately connected to trauma and death (Freud 1961). The revisiting of the traumatic site, as well as the symbolic gesture of abandoning the search for a better future so as to turn back towards the past may very easily lead outside the realm of what Freud called the pleasure principle, the world of desire and satisfaction, towards the inorganic. In that sense the time of the film is as important as the place: similarly to Lajoska’s story, it is set after the time of desire, action, adventure and conquest, when all these have been tried and all have failed. Time as a measurable, calculated forward movement (towards objects of desire) has stopped. So it is time to return.

In the Hungarian context, however, the inevitability of return to the (ambiguous) roots and homeland is a long established poetical figure. Let me only refer to one of the most well-known poems of Endre Ady, arguably the greatest Hungarian poet of the first half of the 20th century, A föl-földobott kő / The Tossed Stone, a key work of the Hungarian literary canon, a poem still many students have to learn by heart in secondary schools. By comparing himself to a stone thrown up again and again only to fall back to the ground, the poem addresses precisely the desire to go away and the inevitability of coming home. Significantly in the context of Delta, it also speaks about a certain sadness (that Ady saw as a national characteristic), which cannot be left behind wherever one goes, moreover it also formulates the intimate connection between returning and death. Ady also rephrases a 19th century figuration of the motherland (well known from such canonical texts of the Hungarian Romantic movement as Mihály Vörösmarty’s Szózat / Appeal, or Sándor Petőfi’s Nemzeti dal / National Song ) in ways that prefigure the connection between incest, the homeland and death in Mundruczó’s film: whereas in the 19th century paradigm the motherland is usually holy and pure, something deserving sacrifice, at Ady it appears simultaneously as a mother-figure and a lover of a passionate love-hate relationship. Perhaps this cultural background is one of the reasons why the (Hungarian) spectator is not surprised at all when Mihail and his newly found sister, Fauna, who follows him to live in the Delta, fall in love and form a strange, incestuous couple on the frontier between nature and culture, life and death, soil and water. Incest is yet another marker of this outside of culture and desire: their “return” to each other is inevitable, without words, outside language, concepts and culture, also lacking the usual dynamism and (cinematic) clichés of desire.

As often in contemporary Hungarian films of return, the characters’ motivations are mostly told by evocative, sensuous images of highly metaphorical spaces (see Király 2015, 179). The most important spaces, in this respect, are the village and the river. The village is mostly represented by the pub, a place of cruel, worn-out faces, human degradation, alcoholism, and the industrial wastelands of the river bank next to the village (where the escaping Fauna is raped by her foster-father). These are the spaces of a cruel, patriarchal order, where – in a twisted folk-tale-like fashion – the “good father” has been killed and replaced by the “evil step-father.” Human order has gone to usurpers, criminals and rapists – the film seems to suggest. The other place, however, is not a harmonic, bucolic Eden, and not even a place of self-fulfilment where one may reach a higher consciousness (as the poets of Romanticism believed): the river in Delta is the place of the sublime, beyond human comprehension, beyond good and evil, where life and death flow together inextricably and inexorably.

Mihail’s most important embodied practice in Delta is building the house on the water. On the one hand, it can be read as an attempt at creating a new life, close to his roots (the dead father’s hut), outside the corrupted human world. Building a new house means finding a new place, and thus a new connection to the world in a new spatial-physical arrangement. However, this new place is on the water, a symbolic element that stands just as much for death as for new life, at least since Ulysses decided to head back to Ithaca. The ambiguity of the project and the place of retreat (as a figure of both life and death) is emphasised by several details. First, Mihail cannot swim, thus choosing the water as a place to escape from the world already signifies the connection between withdrawal and death. Second, the house on the river becomes a place outside, or rather before the patriarchal order, a pre-Oedipal, incestuous paradise for traumatised subjects. This is not only indicated by the brother-sister relationship, but also by their “totem” animal, the small turtle, the object of love of his sister, that was thrown out by their foster-father and lives here. The turtle, in my interpretation, signifies the child-like innocence of their relationship as well as the regressive trajectory of their journeys. After all these metaphorical foreshadowing elements, when the drunk villagers finally come to the log-house and kill the couple, it seems as inevitable to the spectator as Lajoska’s self-mounting or Ady’s returns from Paris to the Hungarian wasteland. Horror, trauma and death are “natural” destinations on these regressive itineraries.

Land of Storms

Szabolcs’s story in Land of Storms is deeply linked with post-regime-change Hungarian dreams of success in the west. He is a footballer in Germany, living in an urban setting together with other sportsmen with international background, in a seemingly tolerant and liberal community, equipped with the usual toys of contemporary consumer culture, smartphones and fancy clothes. The boys train and play football together, drink beer and smoke marijuana together, watch porn and masturbate together, thus more or less fulfilling one of the dominant images of happiness in contemporary Western teenager culture. However, Szabolcs does not seem to fit in. He has “attitude problems”, has conflicts with the coach as well as the other boys, and finally decides to leave.

Though his motivations are only hinted at, of the three films discussed, it is here in Land of Storms that the spectator gets closest to grasping the working of some kind of ideological failure in these films of retreat. The German scenes in the beginning of the film are always without music, and there is always some kind of tension felt by Szabolcs as well as the spectator, which never lets either him or us enjoy these scenes as liberation or joyful self-fulfilment. There seems to be a lack of faith, dissatisfaction or disappointment in the kind of life offered by the West, in cultural connectivity, in the Eastern European subject’s satisfactory integration into the great projects of Western culture. Szabolcs’s alienation from western dreams is already reflected in the very first scene of the film: while the football coach is reciting a prayer- or mantra-like speech to the young players about the feel and love of football, Szabolcs is lying on his side, playing with the grass, instead of lying on his back and looking high into the sky, at high hopes of success, as the others.

One must note that by the time these films were made, the progress-oriented mythology of modernity had become tainted, corrupted and broken. Ironically from the perspective of the Eastern European citizen, the West that we “got” is no longer that West that we wanted to get to during state-socialism. Not only because it is a “real west” (rather than the “fantasy west” people imagined in state-socialism), but also because the “real west” of the 2000s is also a place of economic and demographic crises, shrinking welfare functions, spreading Islamism and terrorism, less and less credible political elites, and a quickly growing New Right. Progress and development has given way to crisis, decline, struggle and disillusionment both East and West of the former Iron Curtain. From a liberal, philanthropist slogan expressing progress and emancipation for all, “building better words” (at least in cinema) has turned into the symbol of the hypocrisy of global capitalism and the ruthless exploitation of human beings for the sake of profit and the System.

In the context of characters who give up the mass-produced dreams of contemporary western culture in order to seek a place of retreat, it is quite significant that in much of recent spatial theory space entails forward movement, becoming, leaving behind one’s roots and physical constraints, that is, conceptualised in terms of the dominant mythology of modernism, while place is something located, fixed, an object of nostalgia, a home. In other words, the concept of place often had a reactionary edge in theory even before returns and retreats became such common themes in Eastern European cinema (see: Massey 1994, 141).

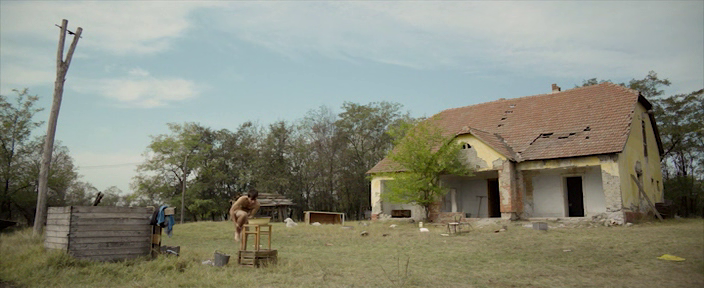

For Szabolcs, this reactionary place, the closet to hide in is his grandfather’s half-ruined house in rural Hungary, in “the land of storms” (Viharsarok), traditionally one of the poorest and most conservative regions in the country. His retreat is often emphasised in spatial terms, in a manner similar to that of Delta, with long shots of the landscape and the house, standing isolated from any human settlement. Significantly, the first time any music is added to the images of the film is when Szabolcs gets off the train and we can face the huge green landscapes of his homeland. These images, in both films, evoke the beauty of nature, the promise of a more authentic subjectivity, but also the loneliness, deprivation and traumatised state of the protagonists. The concept of wounding (trauma) is literally evoked here: when he gets home, because of a previous fight with other lads after a lost match, Szabolcs is bruised and wounded. Restoring the house with his own hands, mending the roof, installing doors and windows (as the old ones were stolen while the house stood deserted) become the basis of a new practice of the self, a symbolic activity of healing, in which the cracks of an injured self can be patched.

In the context of the collapse of the ideology of progress it is quite significant that during their retreats, hidden in these deserted, marginal places, all three protagonists engage in manual activities of great sensuous value. Lajoska’s work on the animals’ bodies, Mihail’s construction of the log-house and Szabolcs’s restoration of the house (as well as his work with bees) can be seen as retreats from the shiny digital theme-park of contemporary urban consumer societies to an “analogue” world based on bodily presence and physical activities that engage all of the senses of human perception. Szabolcs has a smartphone, but we never see him surfing on the net or playing games on it, as many teenagers do in their spare time.

Issues of fatherhood are also present in The Land of Storms, following a pattern similar to the ones seen in the previous films. Father-son relationships are problematic in all three examples, there is practically no understanding between generations. In Land of Storms it is Szabolcs’s father who keeps pushing his son to be a footballer, as a compensation for his own misfortunes as a sportsman. There seems to be very little in common between them, apparently Szabolcs cannot discuss with him either the conflicts he faces in his career, or his homosexuality. However, his relationship with his substitute- or symbolic father, the German coach is no better: most of their interactions consist of verbal abuse and physical violence. His interactions with these two father-figures are conspicuously similar: the age and look of the two elder men, their insistence on Szabolcs’s pursuing his football career, and even the configuration of bodies while training with them (we see Szabolcs trying to take the ball away from them, without success). These similarities become most telling when it comes to Szabolcs’s reaction to the ideological indoctrinations: in his father’s house after such a “typical” father-son conversation, at night when they are already in bed, he turns on his side and assumes an embryo position on his left side similar to the one we saw in the first scene. In both scenes an overhead camera records the events, registering Szabolcs’s difference from the standard, desiring or forward-looking attitude by this regressive body posture (which is the same position that he dies in at the end of the film).

In these three films fathers represent the dominant patriarchal order with its hegemonic masculinities, that is why their sons turn towards other, deeper roots when their lives reach a crisis. Szabolcs moves into his grandfather’s old house, away from his father’s (and from mainstream teenager culture’s) dreams of stardom. As Mihail in Delta, he moves back to the East (something that most people there probably find very stupid and suspicious). In Delta it is the dead father and the mean step-father who play the same roles as the grandfather and the father in Szabolcs’s case. Mihail’s father is long since dead, and the stepfather, his mother’s lover embodies the worst kind of tyrannical, patriarchal masculinity. The first time we see him he is killing a pig behind the house, he is openly hostile towards Mihail, and also rapes his sister, Fauna. In case of Taxidermia, as I have noted above, Lajoska is the exact opposite of everything his father and grandfather was: he neither has the sexual vigour of his grandfather, nor the obscenely huge appetite of his father, for which his father keeps reviling him.

Szabolcs’s difference is coded mostly in terms of gender, though the exact problems he faces in Germany are unclear. This connects his story with those of Lajoska and Mihail, whose alienation and ritual retreats are never really explained psychologically, thus their misery can easily acquire overtones of a more general, philosophical, existential or cultural critical nature. Having left the West, as a young gay man in rural Hungary, Szabolcs quickly becomes an outcast. The house (the most important symbol of his identity in crisis) never gets completely repaired, though he finds help in Áron, a teenager from the nearby village, with whom they become friends and then lovers. Their story is as much about the failure of connectivity as that of Lajoska or Mihail. None of them can make real contact with their home communities or fathers. Though they perform a ritual “attempt of recapturing the deserted, the lost” (Dánél 2012, 117), they cannot succeed, “home is always elsewhere for them” (Király 2015, 178).

Conclusions

All three retreats have ritualistic aspects. Not only the three men retreat from modern lifestyles into closets of their own, but the films themselves also acquire a ritualistic dimension. All three seem to avoid detailed psychological motivations and explanations, instead they show rituals of death and sacrifice. Lajoska turns his father and himself into memorials of a traumatic family history; Mihail, after inviting the villagers to dinner to share the abundant fish they catch (together with plenty of bread and pálinka) in the newly built house, is murdered together with his sister-lover by the villagers in a scene rich in Christian allusions; and when Szabolcs is killed with a knife by his tormented lover Áron, we hear the musical motif of Agnus Dei (God’s Lamb). These deaths follow the age-old logic of ritualistic scapegoating and (self-)sacrifice, and stem logically from the narratives of the films. These Hungarian stories of retreat seem to be exceedingly brutal with their protagonists, they make it clear that one cannot simply turn one’s back to the dominant ideologies and masculinities of contemporary societies, one cannot turn one’s back to a lost past or a lost childhood, ignoring the imperatives of one’s biological and/or symbolic fathers.

I would argue that post-communist cinematic returns and retreats can be interpreted as a reinvention of an old, well-used pattern of behaviour on the part of Eastern-European men. As Maya Nadkarni argues, “the paternalist regime constructed its citizens, regardless of age, as childlike. That is … the retreat into a private realm of action seemingly free of political concerns was in fact the very condition of political subjectivity” (Nadkarni 2010, 200). After the regime change the euphoria of the end of state-socialist dictatorships may have empowered men to change this much-practised pattern and venture out so as to try living more open, active and progress-oriented masculinities. The films of the 2000s, however, show that this empowering myth of emancipation, connectivity, modernisation and progress has been seriously shaken and discredited in the countries of the former Soviet Bloc. Men (in films as well as in life) often choose tactics of retreat, turn back towards their roots, and seek simpler lives in the private realms far from the public battles they have given up on winning.

References

Bazin, André. 2005. “The Ontology of the Photographic Image.” What is Cinema? Vol. 1., 9–

16.Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press.

Bettina van Hoven and Kathrin Hörschelmann, ed. 2005. Spaces of Masculinities. London and New

York: Routledge.

Connell, R. W. Masculinities. 2005. Berkeley, Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Dánél Mónika. 2012. “Surrogate Nature, Culture, Women – Inner Colonies. Postcolonial Readings

of Contemporary Hungarian Films.” Acta Universitatis. Sapientiae. Film and Media Studies,

- 5: 107–128.

Ferge Zsuzsa. 1996. “A rendszerváltozás nyertesei és vesztesei.” In Társadalmi Riport 1996. ed. Andorka Rudolf, Kolosi Tamás, Vukovich György, 414–443. Budapest: TÁRKI, Századvég.

Freud, Sigmund. 1961. Beyond the Pleasure Principle. New York and London: Norton.

Gott and Herzog. 2015. East, West and Centre. Reframing Post-1989 European Cinema. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Jobbit, Steve. 2008. “Subterranean Dreaming: Hungarian Fantasies of Integration and Redemption.”

Kinokultura. http://www.kinokultura.com/specials/7/kontroll.shtml. Last accessed: 05.06.2017.

Király Hajnal. 2015. “Leave to live? Placeless people in contemporary Hungarian and Romanian

films of return.” Studies in Eastern European Cinema. Vol. 6. No. 2: 169–183.

Lefebvre, Henry. 1991. The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell.

Losoncz Alpár. “Válság és affektusok.” http://uni-eger.hu/public/uploads/losoncz-alpar-valsag-es-

affektivitas_56b88f3ad5807.pdf. Last accessed: 05.06.2017.

Massey, Doreen. 1994. Space, Place and Gender. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Mazierska, Ewa. 2008. Masculinities in Polish, Czech and Slovak Cinema. New York and Oxford:

Berghahn Books.

Nadkarni, Maya. 2010. “But It’s Ours: Nostalgia and the Politics of Authenticity in Post-Socialist

Hungary.” In Post-Communist Nostalgia, ed. Maria Todorova and Zsuzsa Gilla,, 191–214. New York, Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Sághy Miklós. 2016. “Irány a nyugat! – filmes utazások keletrõl nyugatra a magyar rendszerváltás

után.” In Tér, hatalom és identitás viszonyai a magyar filmben, ed. Győri Zsolt and Kalmár György, 233–243. Debrecen: Debreceni Egyetemi Kiadó, ZOOM könyvek.

Sághy Miklós. 2017. “Retreat into Spaces of Consciousness.” Contact Zones 2017/ 1. 26-37.

Schissel, Wendy, ed. 2006. Home / Bodies. Geographies of Self, Place and Space. Calgary:

University of Calgary Press.

Sharp, Joanne P., Paul Routledge, Chris Philo and Ronan Paddison, eds. 2000. ENTANGLEMENTS

OF POWER: Geographies of domination/resistance. London and New York: Routledge.

Shaviro, Steven. 2012. “Body Horror and Post-Socialist Cinema: György Pálfi’s Taxidermia.” In A

Companion to Eastern European Cinemas. Ed. Anikó Imre, 24–40. Oxford: Wiley and Blackwell.

Strausz, László. 2011. “Archaeology of Flesh. History and Body-Memory in Taxidermia.” Jump

Cut 53. http://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/jc53.2011/strauszTaxidermia/. Last accessed 10 February 2015.

Széman, Imre and Tamás, Gáspár Miklós. 2009. “The Left and Marxism in Eastern Europe: an

Interview with Gáspár Miklós Tamás.” Mediations. Vol. 24. No. 2: 12–35. http://www.mediationsjournal.org/articles/the-left-and-marxism-in-eastern-europe. Last accessed: 15.06.2017.

True, Jacqui. 2003. Gender, Globalization, and Postsocialism: The Czech Republic after

Communism. New York: Columbia University Press.

Valuch Tibor. 2015. A jelenkori magyar társadalom. Budapest: Osiris.

Teréz Vincze. 2016. “Remembering bodies: picturing the body in Hungarian cinema after the fall of

communism.” Studies in Eastern European Cinema, Vol. 7. No. 2: 153–167. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/2040350X.2016.1155268. Last accessed 13.06.2017.

Warf, Barney and Santa Arias, eds. 2009. The Spatial Turn: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. London

and New York: Routledge.

Woolf, Virginia. “A Room of One’s Own.” 2015. A Room of One’s Own and Three Guineas, 1–

- Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[1] This article was supported by the János Bolyai Research Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, and by OTKA 112700 Space-ing Otherness. Cultural Images of Space, Contact Zones in Contemporary Hungarian and Romanian Film and Literature.