Magyar Vivien

vvn.magyar@gmail.com

Myth and Stylistic Excess: Moments of Slippage in Contemporary Serbian Film (download pdf)

Abstract. Due to the stereotypical image of the Balkans perpetuated by the discursive dominance of the Western perspective, Serbian filmmakers are constantly faced with decisions about dealing with expectations. Mirroring stereotypes and subverting them in order to weaken the postcolonial discourse is a constant issue for Serbian film. As subversion strongly relies on ambiguity, it is often the visual style of a film that carries the subversive undertone. The unique stylistic features of Serbian film – which can be grasped in its attraction to visual excess – provide an opportunity for filmmakers to create a moment of slippage as defined by Homi Bhabha that offers an escape from the compelling world of stereotypes. This self-imposed stylistic otherness acts as a defense mechanism against the oppression of the Western gaze, and in the case of certain films, goes hand-in-hand with a cultural (religious or mythological) reference – such as the appearance of the weeping painting of Christ in The Knife (Nož, 1998), the Fates in Vukovar (Vukovar, jedna priča, 1994), the myth of Iphigenia in The Tour (Turneja, 2008) and the demiurge in The Enemy (Neprijatelj, 2012). Such cultural motifs serve as excuses to provoke a stylistic moment far-fetched from the films’ more or less consistent realism, and as they are inconsistent with the constant appropriation of stereotypes that most of these films seem to succumb to, can be interpreted as stylistic revolts against discursive tyranny. Pointing them out may lead us to a more nuanced view of the last decades of Serbian cinema, constantly balancing between subversion and appropriation.

Keywords: postcolonialism, stereotype, mimicry, Homi K. Bhabha, Serbian film, Balkan cinema

An Introduction to Serbian Cinema’s War Against Stereotypes

Since the breakup of Yugoslavia that resulted in the devastating civil war of the 1990s, Serbian film has been carrying the burden of having to redefine not only itself as a national cinema with unique attributes and cultural roots, but also the perception of the nation to which it belongs, in the eyes of its own people as well as outsiders. Serbian films notoriously engage in the discourse that revolves around the hierarchical relationship between East and West, Balkans and Europe, civilised and barbaric. As stereotypes are played back to their originators, most cinematic works, particularly those of the turbulent 1990s, appear to do more to strengthen the postcolonial discourse than attempt to dismantle it.

At first glance, the majority of recent Serbian films simply reiterate Western stereotypes of the aggressive, uncivilised, barbaric Balkan man and the frivolous, hedonistic, carnivalesque nature of the Balkan lifestyle.[1] If we were to do a quick roundup of the themes and motifs that are commonly thought to constitute Serbian film, we would arrive at precisely what the West desires to see in Balkan works of self-representation: a secluded land with no connection to the rest of the world, ruled by barbaric customs, violence and crime, where the superpotent maniacs that are the male protagonists live their uninhibited lives. The assumption that this is what a Serbian film is supposed to look like comes from the West’s general lack of knowledge about the region and its perception as a distant, exotic, foreign land perpetuated for decades by the media, as well as contemporary films from Serbia itself that do, in fact, reiterate stereotypes, either to comply with the expectations of international audiences, or on the contrary, to subvert the image that is mirrored back to them (whether Kusturica belongs to the former or the latter category, I leave it up to the reader to decide). When aiming to go against these expectations, perhaps even dismantle some of these stereotypes, and at the same time produce a commercially viable piece of cinema, the filmmaker’s options are limited. Due to the ambivalent nature of stereotypes and the thin, almost undetectable line between what is “real” or “authentic” and what is not, it is difficult, if not impossible, for the filmmaker to think outside the box. Marko Živković is right to point out in his book on the Serbian National Imaginary that there is a limit to what, for a given individual or collective subjectivity, it is possible to imagine (Živković 2011, 77–82). It is obviously not the filmmakers’ lack of creativity or inability to portray their own society authentically that results in stereotypical depictions of the region. It is the boundaries of the Serbian national imaginary that confine the filmmaker to a world that uses stereotypes as a language. Any attempt to take up a fight against these stereotypes would have to come from within, by first learning to speak the language.

As Marko Živković notes, the Serbian responses to Western stereotyping can be placed on a spectrum that ranges between the complete and utter acceptance of the West’s negative valuation, through processes that Živković identifies as minstrelisation or voluntary self-denigration, to the maximal exploitation of the positive valuation, through a process known as self-exoticising (Živković 2011, 826–832, 845). The former is the result of a submissive resignation to the discursive oppression of the West; the latter requires a more optimistic as well as opportunistic approach, as it regards stereotypes as opportunities that can be turned to one’s own advantage. Of course, in practice, the two extreme poles of the spectrum are never actually manifested, as each response (or in our case, each film) demonstrates a mixture of the two attitudes in different proportions. What is more, both attitudes provide fertile terrain for subversion. Stereotypes, in order to be subverted, must be adapted first. As Dušan I. Bjelić writes based on Fredric Jameson’s thoughts, subversion exposes and undermines a hegemonic system of stereotypes by means of performative destabilisation (Bjelić 2005, 104). Furthermore, as Milja Radovic notes, subversion invites the viewer to reconsider ideology, but always in a subtle and ambiguous way, through adopting the prevailing ideology as well as its aesthetics to use them as tools of subversion (Radovic 2009, 6).

As subversion is always subtle and ambivalent, it is open to interpretation: and the most subtle tool for providing layers of meaning is style. Even though an attraction to certain tones, such as black humour and a sort of bittersweet, grotesque “magic realism” (a misleading term often used to describe Emir Kusturica’s films) can be discovered in recent Serbian cinema, there is no uniform stylistic tendency that could be outlined. However, what these films do have in common is their obsession with stylistic excess, which stretches from the exuberant use of motifs through the exaggerated depiction of feelings and passions to the visual exploitation of violence.[2] The use of excess as a stylistic tool is a trait that makes these films distinct and recognisable, and very much unlike the cinemas of neighbouring countries (especially the characteristically minimalistic cinema of Bosnia and Romania, countries which, in the eyes of the ignorant Westerner, fall into the same vague and generalised category of “the Balkans” as Serbia, without recognising that each of these national cinemas retain their own unique characteristics). It is within the context of this attribute, the use of excess that I believe Serbian cinema can find ways to take back its position as a subject (as opposed to a passive object being described from the outside) and reclaim its own perspective.

To better understand the process of subversion and its relevance to our topic, let us turn to the methods and concepts of postcolonial theory. The type of subversion that we are about to identify in a number of recent Serbian films is closely connected with phenomena best described by Homi Bhabha’s concepts of hybridity and mimicry. The former refers to the ambivalent nature of the postcolonial identity constructed by the merging of the Self and the Other, where the two identities exist side by side, in a dynamic discourse of differences, without integrating or dissolving (Bhabha 1994, 25, 112). The latter signifies a complex process through which the colonised – or, to use a more generic term, the oppressed – imitates the culture of the coloniser – the oppressor –, adhering to its system of expectations. However, mimicry is defined by ambivalence. The picture that is played back is almost the same as the oppressor’s expectations, but not quite: mimicry always produces a subtle difference that Bhabha calls excess or slippage (Bhabha 1994, 86). Mimicry poses a threat to the authority of the oppressor, as it unmasks the ambivalence of the colonial discourse. Conversely, mimicry provides the oppressed with a chance to fight against the imposed power of dominant culture (Bhabha 1994, 88).

In relation to our topic, Bhabha’s observations can be taken quite literally. In recent Serbian films, the slippage or excess of mimicry that Bhabha describes is generated through stylistic excess. Due to its subtleness and ambivalence, grasping exactly where and how slippage “happens” in films is a daunting task, but we can at least provide a few guidelines as to where to look.

I believe that many recent Serbian films can be described by the use of excess as a stylistic tool, and most produce the kind of slippage that Bhabha describes. However, the films that I am about to analyse have another trait in common: in each case, at a certain point in the film, stylistic excess reaches its peak, and produces a moment of slippage that coincides with, or is provoked by a cultural reference – an allusion to an element of religious or ancient mythology –, resulting in a level of abstraction. Such moments can be considered acts of subversion as they step away from the films’ overall tendency of speaking in stereotypes, and require interpretational codes other than those of Western expectations. Moreover, these moments have an effect on the natural flow of the narrative, which comes to a halt as the viewer contemplates the meaning of the reference on one hand and the sudden stylistic “upheaval” on the other. As the conventional narrative is the most extensive hegemonic system of these films, any attempt to overthrow it, even if just for a brief period of time, can be seen as the film’s struggle to overstep its own boundaries, to subvert its self-imposed rules. To prove my point, I will select a range of films to stand as examples of how visual excess, “fertilized” by a clear-cut cultural reference, culminates in moments of slippage that goes against the established aesthetic as well as narrative norms of the film. All of the following films use the language of stereotypes to some extent, especially due to the fact that all of them are about the break-up of Yugoslavia and the civil war of the 1990s. As most stereotypes build on the supposed inherently aggressive, barbaric nature of the peoples that inhabit the Balkans, films set in a time of extreme violence tend to reinforce a lot of these clichés. However, in the case of each film, there is just enough difference to prove that these films are not simply reflections of Western expectations.

Brought to a Halt by Tears of Blood: The Knife

Director Miroslav Lekić’s film, The Knife (Nož) is a 1998 adaptation of an infamous novel by Serbian writer and politician Vuk Drašković, a book heavily laden with hate speech against Bosnian Muslims. The film is less explicit in its portrayal of nationalism, and contains several ambiguous elements that hint at a desire for reconciliation, but the underlying pro-Serbian ideology is undeniable. The film reiterates the most basic stereotypes about the Balkans in that it explains the ethnic feud with the surfacing of ancient hatreds that have existed for so long that no one remembers their origins. However, the film does more than just tell the story that has been told over and over again: it makes attempts to break the system of expectations that surround Serbian films, especially ones with ideological connotations.

Following a short prologue, the story of The Knife begins on Christmas Eve, 1942. A Serbian Orthodox family is about to celebrate and enjoy their dinner in peace, when they are suddenly attacked by a group of ferocious Muslims. They rape the women and slaughter the men, concluding the massacre by setting their church on fire along with the priest, the head of the family. The viewer is shown a picture of one of the victims lying dead, blood dripping from his wrist. Then, the director cuts to an image of Jesus Christ’s face, presumably a detail from a larger painting. From somewhere above, blood starts dripping on the painting’s eyes and running down its face [Figs.1–2.]. Having seen the previous shot of a man lying dead, the viewer is led to believe that it is his blood dripping on the painting. However, the two images are solely connected by montage: they are never shown in the same frame. Furthermore, such a painting was never seen in the preceding massacre scene that takes place in the dining room. Thus, it appears as though the image of Christ itself were shedding tears of blood, mourning the death of his faithful followers. As questions regarding the painting’s location (could it be a part of the Church’s iconostasis?) and the meaning of the surreal image start to arise, they distract the viewer and divert attention from the plot. The pathos of the image lingers long after the scene is over and the viewers may wonder: did we just see some sort of supernatural revelation? Are we to witness divine appearances throughout the film? Will the transcendental take part in the unfolding of the story?

Of course, such expectations are never fulfilled. The rest of The Knife focuses on a young man’s quest for identity who had survived the massacre as a baby and was raised by Muslims. The powerful image of Christ shedding tears of blood remains the only such apparition in the film, easy to be dismissed as a sort of stylistic impingement or the director’s momentary lapse of judgment that allowed him to succumb to kitsch. The practical purpose of the image, of course, is to solicit sympathy for the Serbs who met a tragic death at hands of Muslims.[3] However, as the image becomes an obstacle that impedes the natural flow of the narrative, and raises questions that take the viewer far beyond the shot or the scene itself, it can also be interpreted as a gap in the carefully woven fabric of mimicry. The fact that it appears at the very beginning of the film strengthens this inclination. The viewers feel misled, even manipulated, just as the shot of the painting was manipulated by the filmmaker. The excessive pathos of the image that commands such complex, ambivalent meaning provides the filmmaker with a chance to take back control, to take the reins from the bearers of expectations. It is essentially the film’s realism that is broken when the thought-provoking image halts the narrative and portrays something surprisingly inconsistent with the realistic world of the diegesis. In the context of the brutal, bloody fight – which complies with the Western stereotype of the barbaric Balkan man perfectly – an icon, worshipped by the followers of the Orthodox religion as if it were God himself, shedding tears of blood inevitably invites pondering over the existence of the supernatural.[4] The director builds three subversive gestures into a single shot: the image stops the narrative in its tracks, subverts the film’s visual realism and introduces a level of interpretation that is completely alien to the rest of the film (the realm of the divine). Within the context of the scene, the image is first and foremost meant to express Christ’s compassion for the Serbian family who have become martyrs. However, on a more universal level, the image of the Saviour shedding tears is a symbol of Christ’s sacrifice to redeem humankind, and as such, a symbol of all selfless sacrifice. Suddenly, the scene is not merely a depiction of a family massacre: it raises questions that point beyond the specific matter at hand with the use of a religious symbol that has a universal meaning. The moment when the film “slips” onto this level of interpretation is when it manages to break free from its own world of simplification and clichés.

Keeping in mind the role of the Orthodox Church and religious ideology in the politics that led to the war of the 1990s, it is not surprising to find religious allusions in war films produced in the era. However, religious references are not the only tools capable of transferring a film to a more universal level of interpretation: next, let us examine a similar moment in another film that connects its own moment of difference to myth.

Caught in the Grasp of Destiny: Vukovar

Vukovar (Vukovar, jedna priča) is a 1994 war film directed by Boro Drašković that tells the story of a young interethnic couple, a Croat girl and a Serbian boy, who suddenly find themselves on opposing sides when war breaks out in former Yugoslavia. The film is a classically constructed melodramatic love story set in the city of Vukovar that likens the war to an unstoppable storm, an inevitable tragedy that destroys the lives of individuals, without acknowledging the role of politics in stirring up the ethnic animosity that led to its outbreak. As the film emphasises the irrationality of war, it complies with Western stereotype of the Balkans as a barbaric land where irrational aggression can tear the community apart any minute without warning. On the other hand, similarly to The Knife, Vukovar also incorporates a moment of slippage that produces a difference from the film’s overall approach.

Towards the middle of the film, Toma, now a drafted soldier in the Serbian army, is wounded in a shootout and fleeing from a group of Croatian soldiers. As he staggers through the ruins of the war-torn city, he finds three eerie-looking women building a fire and cooking meat in a cauldron. They invite him to sit with them, and the soldier, dizzied by his injury, obliges. One of the women rips a piece of cloth from her skirt and bandages his forehead. They inform him that the pig’s meat cooking in the cauldron is for the orphans hiding in a shelter, adding that the animal had fed on human flesh. They offer Toma a taste but he refuses. As he gets up to leave, the women capture a white bird, similar to a peacock, its feathers blackened by dirt and soot. Before disappearing into the smoke rising from the burning buildings, Toma turns back and listens to one of the women explain that according to the butterfly effect, the whole world gets worse each time an offence is committed in the Balkans.

In addition to invoking Shakespearean tragedy with a reference to the weird sisters from Macbeth, the scene also conjures up classical mythology: the three women are incarnations of the destiny-weaving Fates (Greek: Moirai, Roman: Parcae).[5] In ancient myths, they control the destinies of men as well as gods, thus, they stand for the inevitability of fate – making them fearsome and even seemingly evil.

The theatricality of this scene remains unparalleled throughout the film. The three women appear in a sinister tableau vivant: it is as though a curtain of smoke is pulled apart to reveal the Fates standing in a triangle, one sitting on a pile of rubble, elevated above the other two, in a strikingly artificial and theatrically frontal composition [Figs.3–4.]. They look like unfortunate beggars, battered war refugees, and yet there is something demonic about their bulging eyes, their crazed laughter and their bizarre amusement at the fact that eating a pig’s meat that feasted on human flesh can be likened to cannibalism. They speak as though they shared one mind, one knowledge, each of them saying one sentence at a time before the other takes over. The soldier who has played an active role in all of the previous scenes is now a completely passive object in the hands of the Fates. It seems they do not wish to hurt him, but Toma remains wary of them as they capture the white bird, the last remaining symbol of peace.

The tableau vivant is in itself an intriguingly hybrid phenomenon: it is halfway between theatre and painting, unusual, uncanny even, in its strange stillness. Within the context of a film, the tableau vivant is a technique of mise-en-scène that serves the same function as the photograph that Raymond Bellour describes in his essay The Pensive Spectator. Bellour’s photo-within-a-film is a tool designed to freeze or suspend the film with the help of its sudden, unexpected stillness, and inspire the viewer to reflect on what is being shown (Bellour 1984, 120). The appearance of a photograph, according to Bellour, causes a slight swerve in the film’s course and uncouples the spectator from the image (Bellour 1984, 122), turning the spectator into a pensive one (Bellour 1984, 123). Such a pensive spectator is born when the frozen image of the three witches, completely alien to the natural dynamic flow of the moving image, appears in Vukovar. The viewer is instantly drawn away from the immediate context of the film to the more abstract realm of mythology. The appearance of the Fates brings the idea of a higher power (or at least a higher knowledge) into Vukovar, just as the image of Christ shredding blood introduced the idea of the transcendental in The Knife, and remains the only such apparition here too. Moreover, this is the only scene where, through the referencing of the butterfly effect, the viewer is invited to contemplate whether the film is about something more universal than the conflict between the ex-Yugoslav nations in the nineties. The stylistic realism of the film is contorted by the appearance of the mythical creatures, which results in a strange, theatrically stylised episode loaded with symbolism and philosophical questions. It is as if the plot (Toma fleeing from the Croatian soldiers) had been twisted and squeezed out like a rag, to get rid of all the excess to the last drop, then smoothed out once again. It is this excess that makes Vukovar more than “a war film from the Balkans”, as the West would have it. Here too, the cultural reference is paired with an episodic distraction that diverges from the plot, as well as a stylistic discrepancy that subverts the film’s consistent realism. The scene is just as visually excessive, layered with meaning and altogether out-of-place within the framework of the film as the image of the weeping icon in The Knife, thus, it can be interpreted as slippage.

Stopped to Pay Our Respects: The Tour

The invocation of classical mythology and the theatrical style defines a key scene in the 2008 film The Tour (Turneja), directed by Goran Marković. Uniting all the ex-Yugoslav states in a coproduction, The Tour offers a much less biased and one-sided view of the war than the previously analysed films, and uses stereotypes to rework and disavow them.

The film is about a troupe of actors who travel to the war zone in 1993 in hopes of earning some money by entertaining the troops stationed there, only to find that whoever they run into, Serbs, Croats or Muslims, their lives are always in grave danger. Towards the end of the film, the young, naïve actress Jadranka recites a monologue from Euripides’ tragedy Iphigenia to save her fellow players from the Muslim soldiers holding them hostage. Her idea of delivering a performance out of nowhere in the middle of a tense situation is a courageous and desperate act: it is so powerful and so unanticipated that everyone around her freezes, including her companions and the soldiers, and stares at her in awe. Throughout the film, the actors struggle with their own lack of artistic inspiration and their inability to perform passionately and convincingly. However, to everyone’s astonishment, the young actress’s portrayal of Iphigenia’s sacrifice is not strained or unnatural, but sincere and captivating. Here too, the plot is suddenly suspended, and the viewer’s attention shifts: we are no longer focusing on the cat and mouse game between the soldiers and the players, but are trying to draw parallels between Jadranka’s selfless actions and the sacrifice of Iphigenia, a trail of thought which may last even after the film is over – and thus, Bellour’s pensive spectator is born. The director signals the shift from one level of interpretation to the other by slowly moving the camera towards the actress’s face when she begins her monologue, then opening up the shot once more to include those sitting around her, their expressions completely changed, their aggression and fear completely vanished, their eyes fixed on her. The rest of the soldiers gather around as the porch that Jadranka is standing on turns into her stage, and they turn into her audience. None of the other theatrical performances in the film are presented this way: the actors are often shown in neutral long shots, sometimes even from behind their backs (focusing more on the reactions of the crowd than their acting), whereas here, the powerful close-ups of Jadranka’s face augment the sensation of frozen time [Figs. 5-8.].

This particular performance differs from the others seen in the film not only in the way that it is visually conveyed: unlike the previous performances, it is not an interpretation of a patriotic play of questionable artistic value, but of a classical tragedy based on an ancient myth. The significance of this is that the appearance of the myth coincides with what, in the context of this film, can be identified as visual excess (i.e. excessive use of close-ups, exaggerated acting and an increasingly manipulative way of directing the viewer’s attention with the help of composition and camera movement). In this way, the scene becomes yet another example of a film turning against its own set of rules and using a cultural reference to take a step back and temporarily exit the world of stereotypes.

Interestingly enough, like in the case of Vukovar, here too, it is an art form within an art form, theatre within film that carries the subtext or the second meaning. The mythological reference brings together two dimensions: that of post-war Yugoslavia and that of our world, whose innocent inhabitants have been subjected to different forms of aggression since ancient times. The question of victimhood, above all that of female victims, has been a major concern in the study of the possible psychological motives and aftereffects of the war in Yugoslavia, especially considering the horrifying brutality of aggression against women and endless cases of rape committed in the course of the war. Thus, on one hand, Jadranka’s monologue can be understood as an expression of solidarity with the female victims of the war, and on the other hand, as an ode to all innocent victims of violence.

Cornered by Evil Itself: The Enemy

The final film to be analysed in this paper, The Enemy (Neprijatelj) is a 2011 thriller by genre director Dejan Zečević that tells the story of a group of soldiers stuck in a desolate place as they await commands in the first days following the end of the war. As they search the abandoned towns in the area, they find a man walled up in an old factory and take him back to their shelter. Soon, strange things start to happen: the mysterious man seems to have a power that affects the soldiers in a way that they become restless, paranoid and hot-tempered, and eventually turn against each other.

The visual style of the film is fundamentally defined by the fear and tension caused by the notion of a supernatural evil walking the Earth. The presence of the demonic figure creates a colourless world of constant unease, where weak specks of light try to fight their way through the thick, sinister shadows. It is not the closeness of war and its immediate aftereffects that create the ominous atmosphere. The characters are used to the sight of the war-torn landscape, the bombarded town, their rundown hideout, even the sight of dead bodies heaped into a pile. What they are not used to is this seemingly otherworldly power that turns each other against them.

One of the characters, Čaki, an educated man, likens the stranger to the demiurge, the craftsman-like creator of the world, a being that he interprets as a malevolent force, even though he denies believing in it. The soldiers whisper behind the stranger’s back, but he always seems to be watching them and from time to time comments on their suspicions about him: as the “demiurge” delivers his enigmatic monologues, the camera moves closer and closer to him, until the background is completely blurred and his face is torn from the context of the real world. The camera moves restlessly around the room, as if trying to analyse the characters, picking their faces apart with one extreme long shot after the other.

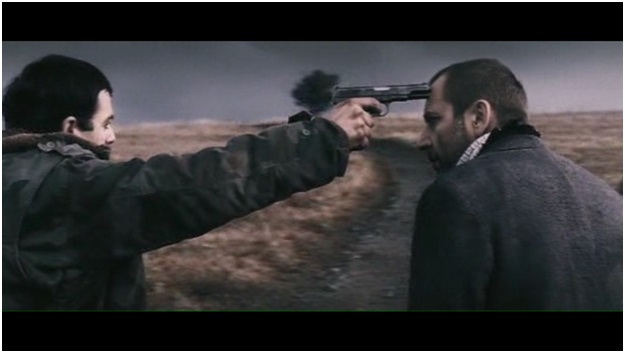

The tense, anxious visual style of the film culminates in a scene where the supernatural power attributed to the mysterious man takes effect explicitly. Towards the end of the film, Čaki is severely wounded by a landmine that accidentally goes off, and is found dying by one of his fellow soldiers, Cole, who keeps the strange man prisoner, and a young girl, a war refugee returning home who had previously joined the soldiers at their hideout. By this time, all the other soldiers are dead, killed by each other in irrational outbreaks of fear and aggression. Čaki attempts to shoot the “demiurge” because he blames him for pitting them against each other, but misses, and accidentally shoots the girl. He himself dies immediately after the shot is fired. Cole rushes to the girl lying on the ground, and orders the stranger to bring her back to life. Suddenly, the girl stands up and tells him that she is alright, and that the bullet only grazed her side. Cole appears to believe that the mysterious man did in fact bring her back.

The scene is highly ambiguous due to the masterfully choreographed camerawork, which can be interpreted as a source of visual excess. When Čaki fires, we are looking at intercut close-ups of his and the stranger’s face, and we are not shown who was hit by his bullet. First, we see Cole embracing Čaki’s lifeless body in grief: only then are we given a shot when we notice the girl’s body, blurred, barely noticeable, in the background. Then, as Cole walks up to the stranger and holds a gun to his head to threaten him, the girl’s body is once again off screen, out of sight. The dialogue between Cole and the stranger is shown as the camera spins around them in a circle: as she is “revived”, the girl suddenly appears out of nowhere, from behind Cole, in the same shot [Figs.9–12.]. We never find out whether she was actually shot and brought back to life by the stranger, or whether she was really unhurt all along, just as we never find out what really turned the soldiers against each other. Was the stranger really the manipulative devil they thought he was, or was it just the evil inherent in mankind brought to the surface by the war that eventually destroyed them?

Again, it is the presence of the (supposedly) mythical creature and the possibility of a supernatural occurrence that trigger the sudden intensification of style. The invocation of the demiurge serves a similar function here as the appearance of the Fates in Vukovar and of Iphigenia in The Tour: the viewer is invited to think outside the strictly fixed perimeters of the film and to consider the main questions posed by it on a philosophical level and in a wider cultural context. We no longer see typical Serbian soldiers senselessly battling each other, but are invited to think about an otherworldly evil that may be out there to corrupt the human soul. This is where the difference or slippage that is meant to secure the film’s unique perspective appears. The achievement of The Enemy (and particularly this one captivating scene) is that even though it is set in a very specific environment, and says a lot about its social and cultural context, it sheds the constraints of stereotypes and brings to life a universally relatable story within the thriller genre that is still deeply rooted in its own unique culture.

Conclusion

The goal of this paper was to shed light on a type of visual and narrative subversion that may serve as an opportunity for Serbian filmmakers to defend themselves against the oppression of stereotypes. As the examples of the analysed films suggest, Serbian directors can turn to mythology and the stylistic excess uniquely characteristic of Serbian cinema to create a moment of slippage that can be understood as a subversive gesture, as it stands in contrast with the rest of the film in several ways. Firstly, it turns into an episode within the film that is more or less independent from the plot. Secondly, it offers several ambiguous layers of meaning that the viewer is left contemplating long after the moment itself is over, and may even affect the viewer’s interpretation of the film. Thirdly, these episodes also serve as acts of stylistic subversion, as their visual presentation differs from the films’ overall realistic style. The examples of films like The Knife, Vukovar, The Tour and The Enemy prove that even if it is virtually impossible for Serbian films to completely free themselves of stereotypes and the expectations generated by them, there are ways for them to produce a kind of difference that marks them as unique works of self-representation.

References

Bellour, Raymond. 1984. The Pensive Spectator. In The Cinematic, ed. David Campany. Cambridge: MIT Press, 119–123.

Bhabha, Homi K. 1994. The Location of Culture. London, New York: Routledge.

Bjelić, Dušan I. 2005. Global Aesthetics and the Serbian Cinema of the 1990s. In East EuropeanCinemas, ed. Anikó Imre. New York – London: Routledge, 103–120.

Radovic, Milja. 2009. Cinematic Representations of Nationalist-Religious Ideology in Serbian Films during the 1990s. The University of Edinburgh (dissertation).

Živković, Marko. 2011. Serbian Dreambook: National Imaginary in the Time of Milošević. Indiana University Press: Kindle ed.

[1] For instance, Emir Kusturica’s Underground (Podzemlje, 1995), Srđan Dragojević’s Wounds (Rane, 1998) or Goran Paskaljević’s Cabaret Balkan (Bure Baruta, 1998) are often accused of adopting the image of the violent Balkans described above.

[2] To put it simply, when watching these films, the viewer is bound to get the impression that there is too much of everything: too much colour, too much noise, too much music, too much laughter, too much crying, too much blood, too much nudity, too much swearing, too much makeup and so on, resulting in an extremely heightened sense of overabundance of everything that appears on the screen. It may not be wrong to presume that this unquenchable desire for excess (and using excess in order to send a message about serious matters such as the state of a society) is now a tradition of Serbian cinema, as it first appeared in the radically outspoken, provocative, ruthlessly taboo-violating films of the Yugoslav black wave that did not shy away from portraying anything at all on screen (with special regard to the works of Dusan Makavejev).

[3] God’s sympathy for the Serbs is directly related to the notion of Serbian victimhood. The myth of the Battle of Kosovo, the Serbs’ most important national narrative, is meant to convince Serbs that they are a chosen people, the Holy Nation. Throughout history, this myth, originating from an actual battle that took place between the Serbian and the Ottoman army in 1389, when Prince Lazar’s army was defeated by Ottoman troops, has been used as an ideological tool to provide Serbs with an excuse to see themselves as sacrificial victims of eternal aggression by outside forces. The myth played a major part in inciting ethnic hatred in the 1990s, and provided the ideological background for The Knife, among other films made in the decade.

[4] It would be interesting to study the difference between a Serbian and a Western viewer’s reaction to such an image. I speculate that the former would feel less alienated by it than the latter, since such apparitions are accepted by the Orthodox religion – several of the so called weeping icons have been approved by the Orthodox Church to be authentic and miraculous.

[5] The weird sisters in Shakespeare’s play themselves are likely to have been inspired by the Greek and Roman myth of the Fates, among other sources (such as British folklore and the Norns of Norse mythology).